Traces of the unknown

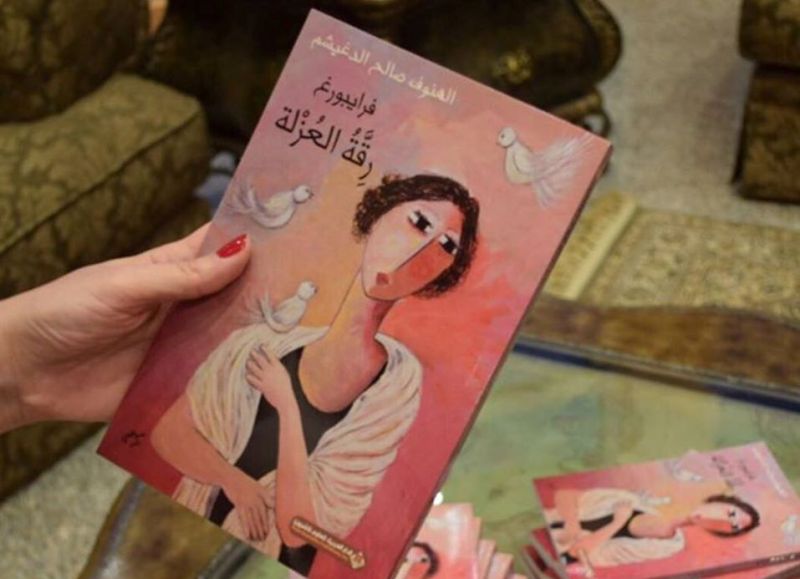

Alhanoof, you open your recently published novel with the question as to what effect places have on our souls. Was it easy to find an answer to that question? Did you cope well with the unknown?

Alhanoof Aldegheishem: Once my years in Germany were almost over, it became clear to me how much place affects the soul. I asked myself: what kind of woman have I become? Who would I be if I hadn′t had this experience? I close my eyes and wish for an answer, some kind of concrete image, but the image doesn′t come. A mysterious woman, perhaps, someone difficult to judge.

A new life came about inside me here, mature and clear. I know what′s going on. I′m the one who shapes that life, nobody else.

To a great extent, this complex and multi-layered life has given me the ability to perceive things and think about them. I have gradually gained the certainty not only that I can survive any turbulence, but also that I′m in a better position, after all these experiences, to deal with anything that might come along and can cope better with my vulnerability and defeats. Nothing throws me off course any more. I′m no longer scared of the unknown. My first impulse might be to say that′s down to the place. But is it not the people who make up a place?

I had no real friends in Freiburg. But I think the city′s whole lightness stems from the fleeting encounters with people for whom my being different is relatively unimportant. It is people who form cultures, which are then connected with certain times or places.

What exactly was the feeling of being an outsider during your stay in Germany? Was it more a state of mind, something that came from inside you? Or was it your surroundings that gave you the feeling?

Aldegheishem: I kept asking myself that very question. To begin with I felt as though it all came from outside. I felt even the tiniest difference. I kept watch on everything that was new. And I had the feeling I was being watched as well. But over time, I came to terms with all the differences around me. I relaxed into a kind of thaw, which I found a pleasant challenge. It was as though the ice all around me was melting, making the horizon broader and me more open towards other people and their different natures as well.

When I watched a squirrel it seemed to call out to me: ″Hey, you don′t come from around here!″ When the rain caught me by surprise its only comment was: ″No wonder – you do come from the desert, after all.″ Even the countless copper coins deposited all over my apartment because I never spent them – on tables, in my jacket pockets – seemed to have a message for me: ″Aha! So you come from an oil-rich state!″

It was dealing with things like this over time that taught me a better way to deal with others. It was as though I had shed a burden. Yet the feeling of being a foreigner, an outsider, not only came from other people and things. It was also the result of a very different culture inside me, my influences, my world view. So it was a complicated and indefinable mixture of what I am and carry around with me as cultural baggage and what the new place and its cultural components bring to the table.

There′s a passage in the novel in which you remember a cat almost being run over by a car when you were out with your father as a child. At the time, your father advised you to write to rid yourself of fear. Do you see the novel as an attempt to drive out fear and the feeling of foreignness by writing?

Aldegheishem: I moved from one culture to another, from my hometown of Riyadh to an unknown city where I was seen as foreign and different. I found myself in enforced isolation. To begin with that was unpleasant and disconcerting. But at some point the unpleasant feeling and my almost allergic reaction to everything new and foreign wore off. I not only came to terms with it, I was actually proud of being foreign and I created my personal exile, my own little homeland that suited me perfectly.

The conflict I had to fight out in Freiburg, between my duties as a mother, a doctor, a female and a foreigner on one side and on the other side the ambitions of an independent woman who wishes to live in her very own world, strong and free, led to a state of extreme inner tension. All I wanted was peace between all the contradictory women struggling against each other inside of me. So I sought a way of life that offered me enough space for all these women to develop freely.

In my loneliness, I wrote – about myself in the city, about the woman I was seeing so clearly for the first time. Through being different, I not only found the path to others but also to myself. In my isolation, I descended to unknown regions of my soul and discovered my intellectual capabilities. Bad memories were cleared out, old behaviour patterns destroyed. Relying entirely on myself, I explored the huge territory where my fears were housed, fears of all that was unknown and incomprehensible to me. Without involving anyone else, I juggled with questions that seethed inside me like volcanoes.

I wrote on trams, in waiting rooms, in the long periods on my own. I just sat down and wrote – jottings on paper, letters to my friends, notes on my iPad and my phone. The idea to write a book only came when my stay in Germany was almost over. It became clear that I had written to escape from the dead end into which my life had led me. I was writing to record the unsettling journey into the depths of my soul, to my true self.

You write: ″Why did it seem impossible to integrate? What makes this difference so blatant?″ My question is whether and to what extent your daughters helped you to survive that time?

Aldegheishem: My responsibility towards my daughters seemed to be part of the conflict I had to fight out here with myself. And yet they did help me find inner peace. They came to terms quite naturally with the strange surroundings and simply didn′t notice the differences. That toned down my over-reaction slightly and gave me emotional support. It was through them that I gradually became familiar with German culture, which they were able to integrate into with very little effort.

What can you say looking back at your childhood, which you spent in a special residential area for faculty of the King Saud University? Did it have a positive effect on your time abroad? Did it help you?

Aldegheishem: The residential area where I grew up was different to the other parts of Riyadh, more child-friendly, it seems. It was easier to make contact with other children and the environment, in that special atmosphere. I lived more or less like children in Germany. When I watched those children I noticed my thoughts returning to another place. That made it easier for me to come to terms with the unfamiliar surroundings in Germany.

You write: “Although everything I wanted has come true, I am still thirsty and the salty taste in my mouth grows by the day.” In your search for success, did you want to prove yourself as a Saudi Arabian woman in a foreign society? Or were you looking for peace and security, a chance to reconcile yourself with the world, as a woman? Did you find any kind of answer?

Aldegheishem: I think that question is still pursuing me. I have no idea what motivated me to seek success. I think the need to be successful is different for women than for men. For men, it′s a more individual need. Women, on the other hand, tend to seek an area to work in where they feel safe and don′t constantly come up against resistance.

You′re active for equal rights for men and women in Saudi Arabia and in your articles you describe women′s situation as a societal dilemma. Is there a real chance, in your view, that the situation will improve in the foreseeable future?

Aldegheishem: Women in Saudi Arabia live in hope. It may be that some things have changed in their favour. But in comparison with elsewhere, women in Saudi Arabia are still very far behind and there is a great deal that needs to be done if they are ever to catch up.

In your novel, an Italian patient of yours recommends: ″Take the knowledge from here and go home with it. I′ve been here for thirty years but my heart beats in southern Italy.″ What do you think of his advice? Where can you find peace? Where do you belong?

Aldegheishem: I′m with Mahmoud Darwish, who said something along the lines of: ″On foreign soil, a rich harvest tastes bitter and the water salty.″ I always think of the Baloch song that tells us: ″It is beautiful, the land of the others. Alive. Rich. Honey flowing in streams. Yet home is still home, no matter how thorny.″

Interview conducted by Hussein Gaafar

© Goethe-Institut 2016

Translated from the German by Katy Derbyshire