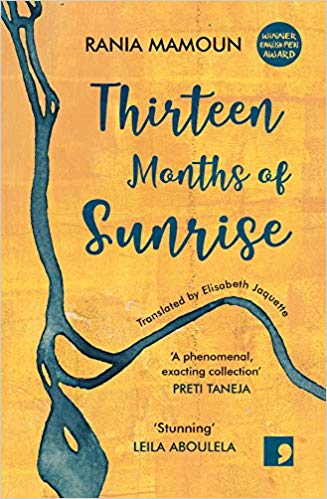

For the sheer pleasure of reading

Rania, the first story in "Thirteen Months of Sunrise" weaves together Amharic and Sudanese cultures, rhythms, tastes, dress and music. Is it important to your work to weave together different cultural forms and genres?

Rania Mamoun: Yes. In my other writings, many cultures appear, although most of the physical settings in Thirteen Months of Sunrise revolve specifically around the centre of the country, particularly the cities of Wad Madani and Khartoum. But in essence, Sudan is a multicultural and multi-ethnic country, even in its languages. A region may speak Arabic, but each has its own dialect. Areas such as the Nuba Mountains and al-Anqsa in the Blue Nile state have their particular cultures, which are different from those of any other region in Sudan. They have their languages, music, stories, and various forms of artistic expression, some of which reflect their tragedies and the genocidal wars waged against the people there.

In this slim collection, you take the short story in a lot of different directions. Are there short-story writers you particularly admire? Why do you read short stories?

Mamoun: There are many writers whose short stories I enjoy; for example, the South Sudanese writer Stella Gaitano, as well as Abdel Aziz Baraka Sakin and Mansour Suwaim. I also like Mohsen Khalidʹs work – although he hasnʹt written anything for a while.

When I read a short story, Iʹm looking for what literary readers generally seek: the sheer pleasure of reading and opening ourselves to the lives of storytellers, and consequently to their cultures, places, and spaces of knowledge. It is as if weʹre adding the lives of all the characters we read about in a book to our own short lives.

There is a great deal of crossing between mental and physical states in "Thirteen Months". But one boundary that seems almost impenetrable is the boundary between the rich and poor. By the end of the book, I thought: itʹs easier to get help from a flea-ridden dog than from an overprivileged human.

Mamoun: Lifeʹs cruelty presses this sort of cruelty on individual hearts, and the harsh life in poor communities – which are marked by oppression, domination, and tyranny – is sometimes reflected in a personʹs inability to reconcile with themselves and with others. Thus intolerance, a lack of mercy, and walls separate a person from themselves.

In these cases, the animal is more sensitive and compassionate than the human being. The difficulties of crossing this border mean the self closes off, stumbling over persistent problems, and this is what happens in the story "Stray Steps".

Lissie: when did you first come across Raniaʹs work, and when did you decide that you absolutely had to translate this collection into English?

Elisabeth Jaquette: I first came across Raniaʹs work with her short story "Passing". Raphael Cormack and Max Shmookler commissioned me to translate it for Comma Pressʹ The Book of Khartoum (2016), a collection of ten stories by Sudanese authors. "Passing" really stuck with me: the mood, the language, the poignancy of the ending.

To date, itʹs still one of the favourite short stories I have ever translated. It was because I fell in love with a story of Raniaʹs that I was drawn to the original collection in which it appears, as opposed to one of her novels.

One of the things that excites me most about these stories is the tension between the gentle attention she has for her characters, and her playfulness with form: "A Week of Love" is structured like a daily agenda, while "In the Muck of the Soul" takes the form of a screenplay, for example.

Rania: have current events in Sudan changed the priorities of your writing?

Mamoun: Yes, theyʹve changed, since Iʹm not writing any literary work; Iʹm writing statements and working with the resistance committees and writing on their behalf, although for security reasons Iʹm not writing using my own name.

The resistance committee was a group we founded after the events of September 2013, and itʹs now leading the revolutionary work in Wad Madani and has been calling for marches and demonstrations in the city since the eruption of the Sudanese revolution. They've been holding a sit-in in Wad Madani since 11 April. It is true that my preoccupation with this political work has influenced my literary output, but itʹs also taught me detachment, and to put the status of the homeland at the top of my list of priorities, after which comes everything else.

Lissie: do you think there are dangers to the book coming out just now, when Sudan is in the news? What would you like to see for the bookʹs reception?

Jaquette: Yes, I do worry that current events in Sudan may end up framing these stories in way thatʹs artificial – a product of limited Western knowledge of Sudan and when the book happened to be released in English. Using current politics as a lens on these stories, or using the stories as a lens on current events, is actually quite unhelpful for thinking about them, I think. Theyʹre set in a specific place, but theyʹre not about place.

Perhaps this is all to say that Iʹm wary of how they may be asked to carry the burden of representing Sudan. I feel theyʹre most interested in exploring human relationships; bounded more by the connections between people, mother and son, daughter and father, lovers, friends, acquaintances. And thatʹs what I hope readers respond to: their sense of brimming, boundless interiority, of human beings as capable, and indeed containing, so much more compassion, empathy, and love than typical roles in society might allow for us.

Rania: is there a literary project you are working on now?

Mamoun: I was working on a novel Iʹd started two years ago, which I stopped writing before it was finished. I no longer feel as though I want to continue it, although I have an idea for another novel that Iʹll soon start here in America, particularly as being in a safe place will assist my literary production.

Interview conducted by Marcia Lynx Qualey

© Qantara.de 2019