Fear of Religious Fanatics

In your work, you paint a gloomy picture of your country as it is today. Is Tunisia really in danger? Is there really so little left of the euphoria of the revolution?

Meriam Bousselmi: We Tunisians had a unique historic chance to take our fate in our own hands. And what happened? In the past, we had a dictator and a red line we couldn't cross. And now we have thousands of dictators and plenty of red lines.

We are living in a time in which many freedoms are being repressed. I ask the question in my piece: As Tunisians, are we in a position to be able to enjoy freedom? Are we in a position to introduce democratic conditions? Can we really respect others? Or are we having a revolution only in order to return to the old times? The Islamists want to force us to dress according to their rules; otherwise they threaten to kill us. We're not even allowed to discuss religion or morality openly any more!

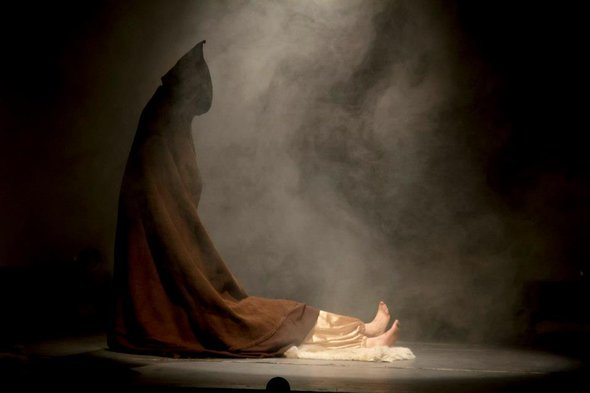

Your latest piece is called "Sabra", which means "patience" but which is also a woman's name. Why Sabra?

Meriam Bousselmi: Because I'm talking about a country which has achieved a revolution. But now it's fighting against measures which could come out of the Middle Ages. A reactionary religious element holds power today in Tunisia and there's a relatively strict censorship. Sabra tells of the situation which we have in our country. I have my doubts now as to whether there ever was a revolution here.

In the first scene, "Wedding of the black homeland", we ask: Didn't we carry out the revolution so that we would have freedom, the rule of law and a civil society? But what we're experiencing now is a radical change of life in Tunisia. It's not just about clothing, it's also about public space, for example, the way people hold their prayers on the beach or in the street. Or they chase actors from the stage during a performance so that they can pray. The strangest things are going on.

You've given the second scene the title "Praise for the lashes." What's that about?

Meriam Bousselmi: It's about the banality of violence. The people who were oppressed before, and who were in prison and tortured, are now in power. They exercise violence against the others; they try to deny the others. It's not a matter of people having different opinions and living together anyway.

They spread fear, and allow the Salafists to be violent towards us in the public space. That's what happened to the philosopher Hamadi Redissi, who said in a lecture, "There is no democracy with the Muslim religion." He was beaten up afterwards, in front of the public, and no-one came to his help.

The third scene is called "An impossible love". I was inspired to write that because of a particular incident. A Salafist was trying to pull down the national flag from the roof of the university in Tunis and to put up the Salafist flag in its place. Nobody did anything about it except for a single student. She climbed on to the roof and tried to stop him. He hit her. So I wanted to ask the question: where are we going in Tunisia? We have got to wake up. We all have a responsibility for the situation!

Fear is the dominant theme in "Sabra". Haven't the people in Tunisia got over fear?

Meriam Bousselmi: Before the revolution, people were frightened of the government, of the police; now it's the fear of a society dominated by religion. Scarcely a week goes by without violence or a sharp attack on writers, journalists, intellectuals, professors or artists.

Is the current situation very threatening for your work?

Meriam Bousselmi: Fear has reached the actors and the musicians who work with me now as well. They refuse to perform certain scenes and say, "I'm afraid they'll beat me up." The government is not on our side; it doesn't protect us. The extremists can attack us in our rehearsal room at any time – even during performances they can beat us up and stop us from showing our work. The actors don't want their pictures on the posters for fear that their houses and cars will be set on fire. They only want to perform with us when we go abroad.

Choreographers and actors have left you because they felt the content was too dangerous.

Meriam Bousselmi: There were ten people involved when we started the Sabra project. They all refused to continue when we came to the rehearsals. They wanted me not to refer to any religious rituals or Suras from the Koran.

Interview by Suleman Taufiq

© Qantara.de 2013

Translation: Michael Lawton

Editor: Lewis Gropp/Qantara.de