"Even we're lost for words sometimes"

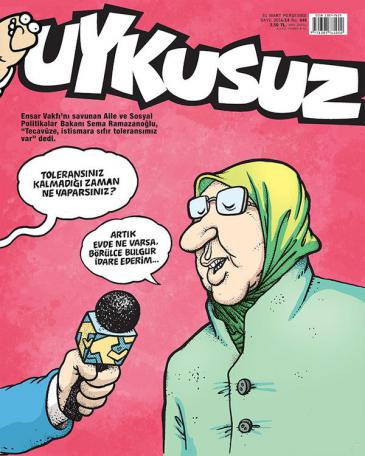

You are one of the publishers of ″Uykusuz″ (sleepless), Turkey's most popular satirical magazine. Other Turkish satirical magazines – Leman or Penguen, for example – are also very successful too. Why is this?

Baris Uygur: There are very few countries in the world where satirical magazines are as popular as they are in Turkey. There are magazines like ″Charlie Hebdo″ in France, for example, which has been published every two weeks since 1992. In contrast to us, it tends to rely more on text, has fewer cartoons and they are sketched with a few, simple pencil strokes. The cartoons in our magazines, on the other hand, are very elaborately drawn.

As far as I know, Turkey is the only country where this sort of magazine is so well established and has such a long tradition. The magazine ″Girgir″ (fun) appeared in 1974. Before that we had ″Akbaba″ (vulture), which had been around since the 1940s and, even earlier, ″Marko Pasa″. The earliest example, ″Karagoz″, goes back to 1923, to pre-Republic Turkey and was printed in the Ottoman typeface. We can say that humorous magazines have been a feature of Turkish life since the days of Sultan Abdul Hamid II. It was after the military coup in 1980, however, when the other newspapers found themselves the targets of censorship that the heyday of satire really began. Back then, ″Girgir″ was really the only opposition and it was the coup that made it political and saw its sales soar to around 500,000. The other satirical magazines also did very well at that time. Another political magazine that was around then was ″Mikrop″ (microbe). It was the one that was closest in spirit to ″Uykusuz″. So, we have a long tradition.

You stress your independence and freedom because you do not belong to any media group. Are there really no topics about which you cannot write?

Uygur: No, because you can always find a way of dealing with any issue, no matter what it is. Of course there are some topics that are officially off-limits, where one risks serious repercussions, perhaps even legal consequences. For example, there is a law that protects Ataturk, the founder of the Turkish state and another that makes it an offence to insult religious values. Abuse of the military services is also outlawed. The crucial thing is how you choose to deal with such matters. You can write about any of these things and still stay on the right side of the law. One must have the professional know-how. That's why we have never fallen foul of the censor.

Is your intention just to make your readers laugh, or is there always a political message?

Uygur: As Foucault once said, "everything is political". Everything we write, or draw, every comic we publish, all of them have a message. Sometimes you only realise much later that a cartoon that appears apolitical at first sight actually does have a political message after all. For example, one of our cartoonists, who works under the pen name Memo Tembelcizer (Memo lazy artist), published a drawing accompanied by the words, "Hands off my porn". At first glance, it appears to be no more than a coarse joke. Memo's point, however, was that if looking at porn on the Internet is forbidden today, who knows what else may be banned tomorrow. The political message of the cartoon and the artist's attitude became evident only in retrospect.

In general, we try to make sure that whatever approach we decide to take, it is something of which we need not be ashamed afterwards. During the so-called postmodern coup of 1997, when the military forced the governing Refah Partisi (Welfare Party) from office, I was still working for the ″Pismis Kelle″ (boiled skull) magazine. Besides the Islamic newspapers, the only ones to complain about the actions of the military were ourselves and our friends from ″Leman″, ″Ustura″ (razor) and ″Cete″ (gang) magazines. A similar scenario developed with the wave of interrogations of alleged members of Ergenekon, an organisation rumoured to be intent on overthrowing the AKP government. We made it clear at the time that we were not taking sides with any of the accused, but that we found the interrogation methods rather dubious.

One might suppose that humorists benefit most when a country is in a difficult situation. Is that really the case?

Uygur: You must remember that if the situation in a country is not good, then it is not good for anyone, humorists included. There are times when we become very envious of our Dutch colleagues and wish we could work like them. They are free to devote themselves to their work with nothing else to distract them. Since the Gezi Park protests we have been seeing people dying or beaten up. It is something that affects us deeply. Sometimes we are so badly affected that we don't know how to react. Then it is good to be part of a team. One of us will always come up with an idea, a way of getting to grips with an issue.

Many and often very funny cartoons have appeared on social media sites such as Facebook or Twitter since the Gezi Park protests. Are they competition for you?

Uygur: To some extent they are competition, but the humour on social media sites is not the same as what we do. It is much more of the moment. Often it involves funny responses to recent events, sometimes a joke, very funny at the time, but a week later, not funny anymore. Because we are a weekly magazine, our humour has to be a bit more durable. At the beginning of each week, we sit down together and discuss which issues we want to tackle and how we are going to do it. Nowadays, we actually publish our first page online before it goes to print, effectively claiming copyright on our jokes.

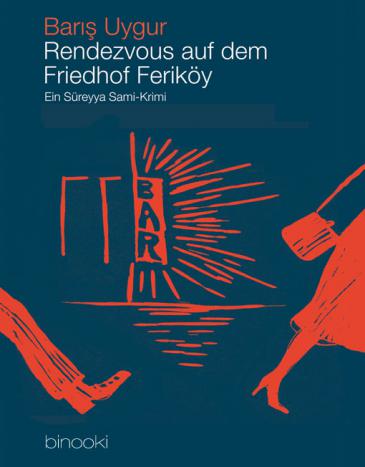

Crime stories appear to be very popular in Turkey. Your own novel, "Ferikoy mezarligi'nda randevu" (Rendezvous at Ferikoy Cemetery), the first volume in a series featuring police officer Sureyya Sami, was so popular that it went to second and third editions in the year of publication. What is it about crime that makes it so popular?

Uygur: Crime stories have always been best-sellers in Turkey and some very good novels have been written here. The first wave of popularity came in the 1960s and 70s. After translator Kemal Tahir finished translating the American Mike Hammer crime stories into Turkish, he decided to have a go at writing more, in the same style, himself. He wrote another ten of them, sitting at his desk with a map of New York, where the novels are set, spread out in front of him. In my opinion, his books are even better than the originals. In the 1980s, the interest in crime novels decreased slightly. Then, a few years ago, the genre experienced another boom and a new generation of younger crime writers arrived on the scene.

I love the books of writers such as Dashiell Hammett or Lawrence Block. At first glance, one might think that crime writing is a genre that limits its authors. But in fact I can work my own opinions and attitudes to certain things into my books. The crime novel forces me to confront reality and when I write about reality, it becomes easier to bring my own feelings and thoughts into the novel.

Interview conducted by Ceyda Nurtsch

© Qantara.de 2016

Translated from the German by Ron Walker

Baris Uygur was born in Eskisehir, Turkey, in 1978. He studied communication science and history and worked as an advertising copywriter. In addition to his work as a writer for the satirical magazine Uykusuz, he also has his own music label. His debut novel has been published in German as ″Rendezvous auf dem Friedhof von Ferikoy″ (2014) and is published by binooki.