Hornets' nest in Beirut

Mr Moukarzel, you are editor-in-chief of "Ad-Dabbour", one of the oldest magazines in Lebanon. Could you describe the circumstances in which "Ad-Dabbour" was founded?

Joseph Moukarzel: "Ad-Dabbour" was founded by my uncle Youssef Moukarzel in 1922. He was born in Egypt and was influenced by the Nahda (the Arab cultural renaissance that began in the late nineteenth century in Egypt – ed.). He worked there as a lawyer but he always wanted to come back to Lebanon. He finally came back in 1921 and fulfilled his dream of establishing "Ad-Dabbour" in Beirut in 1922. He was following his vision; for him, freedom of expression is the first step towards democracy.

Why did your uncle choose to establish a satirical magazine and not a political one?

Moukarzel: Because he said that the best way for a country to claim to be democratic and to have freedom of expression is to have a satirical magazine. He wanted to prove that the Lebanese people are capable of building and living in a free and democratic country. However, this was a challenge under French rule. Youssef Moukarzel was sent to prison and was physically harassed several times, but he continued his effort until his death in 1944.

"Ad-Dabbour" was forced to close in 1977 during the Lebanese civil war, but you finally re-established the magazine in the year 2000. What are the limits of political caricature and satirical magazines today?

Moukarzel: There are no limits! When we relaunched "Ad-Dabbour" in the year 2000, the Syrians were still in Lebanon, and there was no liberty. But we started to publish and people called us and said "God bless you".

My friend Gibran Tueni and I (Gibran Tueni, former editor of the daily newspaper An-Nahar, assassinated on 12 December 2005 in Beirut – ed.) used to say: "There are limits, but we always have to push them. They will hit us, but the limit will expand." That was what we did, we pushed the limits and everybody followed.

It was a kind of resistance and a war of expression. We were fighting against the pressure of the Syrian regime. We received death threats; we had to have bodyguards, and the police were securing the street in front of our office and at home. We knew that there would be assassinations, and Gibran paid with his blood.

Is there a red line when it comes to satirical caricatures on the subject of religion? Can you make jokes about religious figures in Lebanon?

Moukarzel: No, there are no limits here either, especially since many religious figures speak out about politics in Lebanon. If they do, we have the right to criticise them. And we do. However, we criticise them in a positive way without disrespecting the person or their religion. We are attacking their political position and discourse, not the person or the community they represent. For instance, we draw caricatures of Hassan Nasrallah, the Secretary General of Hezbollah, but we have to respect him as a charismatic leader and sheikh of his community. We must not be mediocre; we have to maintain a certain intellectual standard in our drawing.

You are, of course, aware of the caricatures about the prophet Mohammed, which have been published in various Western newspapers and satirical magazines in recent years, and about the respective reaction in various countries across the Arab and Islamic world. What is your perspective on this as an editor of a satirical magazine in the Middle East?

Moukarzel: I have said this many times before. My opinion is this: when this Danish newspaper drew caricatures of the prophet the first time, they did not know what they were doing. However, whenever caricatures were published in Western magazines after that, it was pure provocation. And I have to say, it was not only the Muslim extremists who condemned these caricatures, it was also the absolute majority of moderate Muslims. I think we have to tackle and resolve the problem of religious extremism in the world, but you cannot do so by provoking people.

I discussed this with the artists of Charlie Hebdo in France (a French satirical newspaper, which published cartoons of the Prophet Mohammed in November 2011 and September 2012 – ed.). I told them in a meeting in France, you are provoking people and you are responsible for every person who dies as a result anywhere around the world. The question is: what is positive about criticising the prophet? I do not see any advantage for today's society in doing so. Our objective is not to destroy the world; our objective is not to criticise for the sake of criticising. As my uncle, Youssef Moukarzel, the founder of "Ad-Dabbour" said: "We have to put our finger on the wound to get to the bottom of the things in order to solve the problem." The aim of satirical criticism should be to make the world a better place.

In your experience, is there such a thing as a unique Arabic or Lebanese caricature? Or is it just the context that differs while the underlying idea of satire remains the same whether you are in Paris, Berlin or Beirut?

Moukarzel: This is a very tough question. I think that caricature is a form of expression that must relate to and be in accordance with the society and its way of thinking. The message sent out by the image is the same anywhere, but the range of perception of an image is very large. Everybody translates an image into his or her way of thinking, using his or her cultural baggage. For instance, we focus on very clear contexts. The text of our cartoons is in Lebanese, not in the standard Arabic language. Our target audience is not the Arab world, but Lebanon.

As you said, "Ad-Dabbour" publishes in Lebanon, a country known in the region for its freedom of expression. Do you think that a project like "Ad-Dabbour" would be possible in Baghdad, Cairo, Abu Dhabi or any other capital in the Arab world?

Moukarzel: No, I don't think so! "Ad-Dabbour" is the real proof that there really is freedom of expression in Lebanon. I am not in any political party and I am against everyone including the state, the army etc. Therefore, if somebody does something wrong, I criticise him directly, and I do not face major problems or serious pressure any more.

We are not a pan-Arab journal and we do not want to be because you cannot change anything in the Arab world through freedom of expression because it doesn't really exist there. There are no democratic countries.

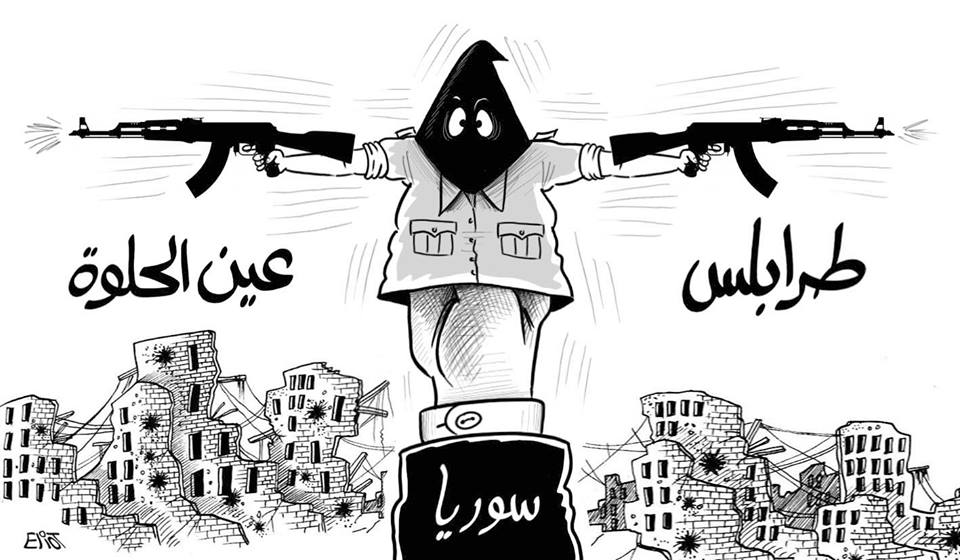

Ten years ago, they established their own "Ad-Dabbour" in Syria; it even had the same name. It didn’t work because the Syrian version only criticised the USA. That is nonsense. How easy would it be for me to make a journal that criticises Israel? Very easy! Attacking Israel will please everybody in the Arab world; this is in no way proof that freedom of expression exists.

Of course "Ad-Dabbour" criticises Israel, but it also criticises Lebanon, Syria, Saudi Arabia and Qatar. We have to criticise everybody who deals with Lebanon in any kind of way. This is why we are not accepted in other Arabic-speaking countries and "Ad-Dabbour" does not have the permission to be sold elsewhere.

Many Western commentators wrote about the unique power of the Internet and social media in the Middle East, especially in relation to the Arab spring. Do you see any opportunities for "Ad-Dabbour "in this field?

Moukarzel: Social media is a must today. But our main objective is not to have as many followers as possible. First of all, we have to survive economically. We cannot survive economically if we go completely digital. This is why "Ad-Dabbour" will remain a printed magazine. With the Internet, our main objective is to touch the millions of Lebanese people who live abroad. These people need the opinion of "Ad-Dabbour". We also intend to launch an interactive website for this purpose in the future.

Interview conducted by Björn Zimprich.

© Qantara.de 2014

Editor: Aingeal Flanagan/Qantara.de