"Religious groups need to be transparent"

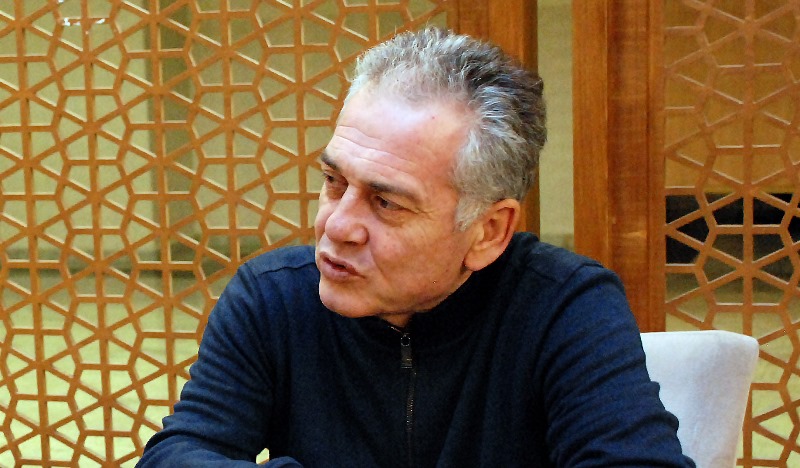

You have recently received death threats. Why?

Mustafa Ozturk: I represent the protest approach. For me, religion is not about regulating the nitty gritty of daily life in accordance with the sacred texts. Religion conceives that basic principles and theorems construct the human being, based on morals and ethics. Yet Muslim individuals should also benefit from philosophy, science and received wisdom, because I believe that religious texts are not applicable for all times and kinds of sociologies. For those taking the traditional approach, however, the situation is the opposite. They claim that even if the text dates back 1,440 years, it is still applicable. I, on the other hand, believe that God addressed the people in and of that time, as well as in the abstract, in accordance with basic principles such as justice, the oneness of God and social solidarity.

Take slavery, for example, which is mentioned in the Koran. If we think like the traditionalists, we can assert that because God mentions it, slavery cannot be abolished. Yet slavery is not a universal norm. Back then, it was not possible to abolish it; religion merely proposed the regulation and humanisation of the system. What makes me sad is that although the Koran implies that slavery should be abolished, it was Western civilisation that ultimately banned it.

You have been defending these ideas for a long time. Why are you experiencing an increase in attacks now?

Ozturk: My instincts tell me that those who are behind the attacks consider me a threat to their traditional views, because when I defend my ideas, I am able to debunk their traditional arguments. I hit them with their own weapons. They can see that my ability to convince people is growing stronger. We are also in the run-up to local elections. Those who attack me are trying to tell the powers that be "look how powerful our group is? We can harm anyone we call a target, so youʹd better listen to us."

Sayın @aysekarabat'ın yaptığı röportaj, https://t.co/KTy55fN0gG adresinde İngilizce olarak yayınlanacak. pic.twitter.com/YC0UTTVlhh

— Mustafa Öztürk (@ozturktefsir) 12. Januar 2019

Why do some Islamic groups feel the need to boost their power in the political arena?

Ozturk: They are out to seize control of certain state institutions like the Diyanet – the national religious affairs directorate – that regulates all Islamic issues relating to public life and the country as a whole. Nor am I the only Islamic scholar to have been targeted. Common to all these targets are their relations with the Diyanet. They are seeking to provoke pious Muslims, saying "you see, Diyanet is publishing and supporting the works of people who defend ideas contrary to our beliefs. So stand up and take action." By doing so, they hope to establish hegemony over the religious institutions, seizing control of them in order to determine religious policy in Turkey. Moreover, the economic potential is huge. If Diyanet publishes a book of yours, for instance, and directs all of its members to buy one, you can make a fortune in a single day.But the government believes that it was a religious community, the Gulen organisation, which first infiltrated state institutions then organised a military coup in 2016. Does this mean lessons were not learnt?

Ozturk: The state apparatus in particular has learnt its lesson. However, let us not forget that in Turkey it is a recognised fact that the pious masses support conservative politics. These masses are not individualistic; they prefer someone else to do the thinking for them.

Thinking is too much like hard work. Thatʹs why they fall prey to such bodies and organisations. Moreover, Turkey boasts between 40 and 50 such organisations: politicians cannot afford to always being saying no to all of them.

Some organisations, letʹs say around 15-20 of them, exist within their own boundaries, but the rest are seeking to further their own interests. For example, a construction firm may work for them, yet it isnʹt clear whether this firm is a financial entity or religious community. The Diyanet and the Higher Education Board are two of their favourite targets.

What needs to be done to curb these religious bodies, hungry as they are for political and economic power?

Ozturk: It would be fascism to tell people that they are only allowed to believe the official line of religious discourse. What is also very wrong, however, is that you currently need to be affiliated to a certain body or organisation to ease your accreditation at some state institutions or derive economic benefit from said institutions. The religious organisations need to be legalised and officially recognised. They should have plans and clear agendas. They need to be held accountable, open to monitoring by an official institution such as the Diyanet, or even maybe a ministry. They need to be transparent.

You have said that you will leave the country because of this climate of intimidation. Turkey has suffered a brain drain recently, but it was generally secular Turks who chose to leave. Is it now the turn of the conservatives?

Ozturk: Conservative members of society who are not a part of any religious structure yet practice religion as individuals, who are supporters of freedom of thought, and who complain about cultural desertification in the field of religious studies are unhappy about the situation.

I am certain about that. Iʹm unsure, however, as to the extent of the phenomenon and whether you could say it had reached the level of a brain drain. I personally do not want to leave, but I am becoming a target of social lynching. Living in fear of being killed by lunatics who believe that killing me would be their ticket to heaven is not easy.

What exactly are conservatives concerned about?

Ozturk: Broaching controversial issues in the theology faculties is becoming increasingly difficult. Students might record your voice, write up a transcript and turn it into an official complaint to send to the Higher Education Board. Speak at a conference or write articles for a newspaper and some citizens are likely to be disgruntled. They may then write complaint letters to Cimer. [Cimer - a department under the Turkish Presidencyʹs Communication Centre to which citizens can write e-mails about their complaints, as well as requests. In 2017, more than 3 million e-mails were sent to Cimer.] Four to five complaints are filed against me every day. It is hard to swallow. The situation was not like this 5-10 years ago, which means that those engaged in such activities feel at liberty to do so.

What measures could be taken to combat this "cultural desertification" and help people breathe freely again?

Ozturk: Recep Tayyip Erdogan has said that as a country we need to improve in the fields of education and culture. Despite this, I havenʹt witnessed any steps being taken to effect any change so far. In Turkey, it isnʹt the civil society taking the lead and then getting the backing of politics; itʹs the other way around. Of course, we can discuss the rights and wrongs of this, but it is how things work here. In the Turkish cultural code, the state is the shadow of God on Earth. Were the president to repeat his appeal for an update in religious understanding, we might suddenly see a change in the current climate.

Interview conducted by Ayse Karabat

© Qantara.de 2019