The Gaping Void in the Debate over Iran

Ever since Iranian President Mahmud Ahmadinejad's remark that Israel should be wiped off the world map was beamed around the world, the Islamic Republic has been viewed by many as a direct threat to the existence of Israel. This remains largely the case despite revelations that Ahmadinejad's comments at an insignificant student conference in October 2005 were in actual fact a quote from Ayatollah Khomeini, which correctly translated reads: "this regime occupying Jerusalem must vanish from the page of time".

Later clarifications from Ahmadinejad to the effect that his comments on no account implied belligerent intent and that the Palestinians must determine their own fate did little to change the impression that the declared goal of the new government was the destruction of Israel. Initially surprised by the reaction to his speech, Ahmadinejad then realised how the subject could bolster his own image. As a consequence, attacks on Israel and later, denial of the Holocaust, became integral elements of his speeches.

No belligerent intent

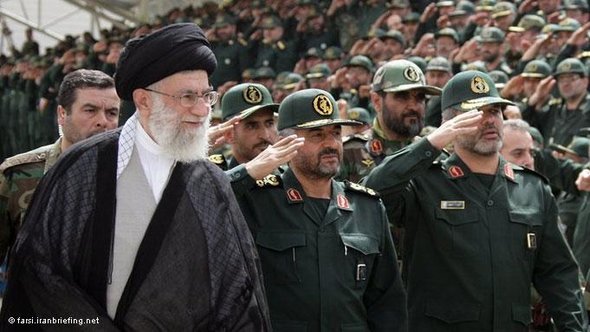

It is beyond question that Iran's criticism of the "Zionist regime" is more than a rhetorical ritual aimed at affirming Tehran's own anti-Imperialist identity. The rejection of the Jewish state by the Iranian leadership – which runs right through to Supreme Leader Ayatollah Ali Khamene'i, who as supreme commander of the armed forces ultimately decides on whether to take the country into war – is beyond doubt.

Just as in Arab nations, the majority-held view in Iran is that Israel's treatment of the Palestinians is a scandalous injustice. But it would be wrong to equate this outrage with a readiness for war. For most Iranians, the fate of the Palestinians was never anything more than a peripheral issue. To start a war against Israel and its allies because of them was never considered as a serious prospect in Iran. An attack of this nature would also fly in the face of a foreign policy approach that has over past decades been less aggressive and more defensive and pragmatic in nature.

The export of the Iranian Revolution first propagated in 1979, which unsettled many Arab nations, was given up just a few years later. After the end of the 1988 Iran-Iraq War, Tehran adopted a reactive rather than aggressive stance and allowed its decisions to be influenced more by interests than by ideology.

For example, during the Nagorno-Karabakh War (1988-1994) Iran threw its weight behind Christian Armenia against Shiite Azerbaijan. During the Tajik civil war (1991-1997), Iran did not support the Islamic opposition, but assumed the role of negotiator.

Following the withdrawal of Soviet troops from Afghanistan, Tehran supported the Shiite minority militia in the civil war. When the Taliban massacred thousands of ethnic Hazara Shiites in Mazar-i Sharif, Tehran threatened intervention in September 1998, but played a subordinate role in comparison to Islamabad, Washington and Riyadh.

Willingness to cooperate on a political level

When the US and the Northern Alliance targeted the Taliban and Al-Qaeda in the wake of September 11, this was met with emphatic approval in Tehran.

The Iranian government also conducted itself in a cooperative manner when US troops toppled the Iraqi dictator and Iran's arch enemy Saddam Hussein in 2003. In the years that followed, reports of arms shipments to the Taliban and Al-Qaeda could never be verified and also enjoy little credibility in view of the two groups' anti-Shiite stance. Tehran was certainly not unhappy about the rebellion in Iraq and Afghanistan, but preventing a Sunni resurgence in Baghdad and Kabul represented a greater priority than the US troop withdrawal.

In Iraq, just as in Bahrain, Kuwait and Saudi Arabia, Iran always perceived the Shiites as natural allies which it sought to foster and support. For Sunni leaders in Manama, Kuwait and Riyadh, Tehran always represented a potential threat in its role as protector of the Shiites. But repeated Shiite protests and rebellions – for example in Bahrain – were never as a result of support from Iran, but rather triggered by repression at the hands of authoritarian ruling dynasties.

A militia dependent on Tehran's goodwill

The Hezbollah movement in southern Lebanon was an exception. Established by the Iranian Revolutionary Guard in the fight against Israeli occupiers, the Shiite militia and party grew over the years into a national power. A defender of national integrity with a strong social network, the movement gained respect among Shiites and influence in Beirut. Although it receives support from Iran in the form of weapons and money to this day, Hezbollah was always more than a militia dependent on Tehran's goodwill.

In the case of Syria, the alliance with the Assad clan was maintained less for cultural-religious reasons, and more for political-pragmatic ones. Members of the ruling dynasty may be Shiite minority Alawites, but their faith differs fundamentally from that of Iran's Twelver Shiites. In addition, the alignment of the Damascus regime was always secular, with no ideological intercepts with the Ayatollahs in Tehran.

Despite Iran's actually rather defensive and reactive foreign policy approach, its image as a belligerent state pursuing its goals without regard for human rights and the rule of law endures to this day. As well as brutal repression at home, this is also due to the repeated attacks and assassinations of exiled politicians carried out by the Iranian intelligence service abroad.

In addition, because of the many rival centres of power, the regime pursued what was often a contradictory foreign policy that made it appear incalculable.

This impression was further enhanced over the past few years by the frequently erratic policies, extremist rhetoric and eccentric behaviour of Ahmadinejad himself. With his verbal attacks on Israel, his Holocaust denial and his claim on a direct line to the Messiah, he has over the course of just a few speeches destroyed the trust built up in previous years by his predecessor Mohammed Khatami. This perception rarely considered the fact that quite apart from the tirades, Iran's foreign policy has remained largely unchanged.

The Supreme Leader's omnipotence

This fixation with Ahmadinejad has also frequently masked the fact that in foreign policy decisions, it is not the president, but the Supreme Leader who has the last word. When Ahmadinejad exits the stage after elections next year, Khamene'i will still be the one pulling the strings.

As a cautious, conservative power politician, his primary goal was always to safeguard the system and preserve the status quo. He balked at making any fundamental changes as well as radical and risky decisions.

A nuclear attack on Israel would however be just such a risky move. It would be a breach of taboo that the international community would not allow to go unpunished. The consequences would not only be nuclear retaliation by Israel, but most likely western intervention to topple the Tehran regime. Iran could possibly still count on its ally Venezuela in such a situation, but even that is not certain.

Rather than Israel, the Islamic Republic would disappear from the political world map. Why anyone in Iran would want such a thing is not the smallest gaping void in the current debate.

Ulrich von Schwerin

© Qantara.de 2012

Translated from the German by Nina Coon

Editor: Lewis Gropp