The Shia shakedown

"Kingdom without a heaven" is the title of the essay – a piece on religious history that is geared toward an academic audience. Not until he is halfway through the text does the reader learn where the said kingdom is located and why it has lost its heaven. The author tells therein of a personal encounter: he recently received a visit from a scholar from the holy Iranian city of Qom, who reported that these days many of the clerics there also believe that the Koran tells the story of a dream once dreamt by the Prophet.

"The scholars now too? I responded indignantly and asked my visitor to tell me on what basis they made this claim. It was all quite simple and understandable, he replied: to see or hear something that others do not perceive is, as we know, an illness. If someone claims he can hear or see something in a waking state that others cannot hear or see, we will most likely send him to see a psychiatrist. If we assume that the Prophet Muhammad – peace be upon him – heard the Koran verses recited to him while in a waking state and others could not hear them, then – God forbid – we are dealing with a case of hallucination. But then the Prophet would have to be considered mentally ill – and what kind of scholar would ever come up with such a moronic idea?"

After recounting this episode, the author returns to the actual topic of his treatise, a philosopher from the 13th century.

A raging fire

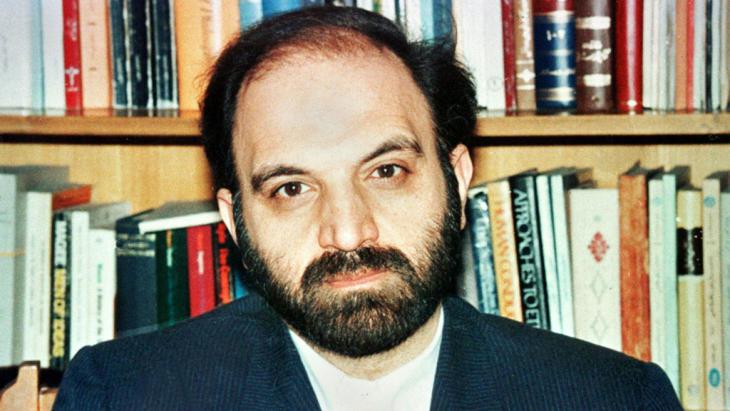

The author who reported on his disturbing encounter is named Nassrollah Pour Djawadi and he is well-known to all theologians, writers and political activists in Iran. The 74-year-old earned a degree in philosophy in the USA and is author of dozens of books on the history of religion and philosophy. Being a poet as well, Pour Djawadi′s style of speech and writing is markedly singular.

In the early days of the Iranian revolution, he sat on the committee set up by revolutionary leader Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini to purge the universities of "un-Islamic elements". Later, Pour Djawadi headed an institute that oversaw university publications. The institute published nearly 2,000 books for the universities.

But those days are long past. Pour Djawadi was dismissed from his office a decade ago and sent into premature retirement. Now he is finding his voice again, especially when the need is pressing. And the situation at the moment is tantamount to a raging fire. Pour Djawadi's text, written only a month ago, deals with a fuse that was laid three years ago and has yet to be extinguished. On the contrary: according to the author, it has long since reached the heart of Shia scholarship in the holy city of Qom.

Anxious Muslims

How did Muhammad come to write the Koran: in a dream or by divine inspiration in a waking state? Is the holy text the word of God, as Muslims worldwide believe, or is it Muhammad's recounting of a dream narrative? These are fundamental questions that the average Muslim needs to contemplate seriously, because they involve the very foundations of the faith. For a believer, the Koran is and will always be "کلام اله" ("kalam Allah": the word of God), conveyed in Arabic by the Archangel Gabriel and received by Muhammad in a waking state. For Muslims, there can be no doubt of this.

And yet, dream versus inspiration is a topic that even BBC Persian spotlighted last summer in two long rounds of discussion. The Persian-language station is regularly watched by 70 percent of Iranians, as Nosratollah Zarghami, former head of the Iranian state radio, admitted a year ago.

Dozens of posts on this hot-button topic can currently be read on the British station's website.

First the messenger, then the message

So Muhammad was a dreamer and the Koran but a dream story? If an atheist, an agnostic, a Western Orientalist or an ex-Muslim were ever to dare to foist such a monstrous claim onto the world, the Shia clergy would simply ignore it, or at the most shrug their shoulders. After all, nothing else is to be expected from adversaries such as these. And any attempt to refute everything that is currently being written and said against Islam nonstop worldwide would take an army of scholars and authors.

But this thesis comes instead from a faction that cannot be ignored. This is why the idea of the dream of the Prophet has become such a nightmare for Shia scholars. For the last three years, the assertion has stirred up a tempest that refuses to die down. No one can afford to ignore it – whether philosopher, theologian or scholar. Grand Ayatollah Makarem Shirazi, the most influential religious leader in Iran, was even compelled to write a detailed opinion on this "renegade and hostile" thesis.

The debate goes on. Every day someone somewhere feels called upon to bring forth a new argument for or against it. Searching for the two words "رویای رسولانه" ("royaye rassulaneh": prophetic dream) on Google, one can get an idea of the level of unease and insecurity that is spreading in particular among the Shia clergy.

But why has this controversy been spiralling without end for three years, taking on ever new twists? The answer: because the author of the thesis on which it is based is none other than Abdolkarim Soroush – a man who is an institution. And for a Shia scholar, the "who" has always been more important than the "what". Therefore, before we consider the contents of any axiom, we first have to ask who put it into the world. This principle of "علم الرجال" ("elm al-redjal": the scholarship of men) is compulsory for every cleric: first the messenger, then the message.

A supreme authority

In modern Shia, Soroush is a messenger no one can ignore. Some call the 72-year-old the Martin Luther of Islam and the Times Magazine named him one of the 100 most influential people in the world. Until his unavoidable exile 20 years ago, Soroush was the philosopher of the Islamic Republic. Republic founder Khomeini praised his books and appointed him to the "Staff of the Cultural Revolution". While still in Iran, Soroush lectured not only at the country's modern universities but also on behalf of the ayatollahs. Students of Oriental literature have written theses about him and he is the subject of research in Islamic Studies.

Ever since he was forced into exile, however, his words and texts seem to sigh a breath of relief – physically and mentally. He addresses his rousing treatises not so much to other exile Iranians as to the Shia clerics in his homeland, whose language and way of thinking he is intimately familiar with. Soroush's dream thesis is not the only idea of his that is shaking the very foundations of the beliefs held by the majority of Muslims.

Soroush writes: "The language of the Koran is purely human and secular. God did not speak, nor did he write a book. Muhammad was a historical person, speaking in God's name. And the divine revelation was nothing but Muhammad's personal experience. His description of this world and the hereafter is based solely on his tribal experience in Saudi Arabia 1,400 years ago."

According to Soroush, the Koran is an exact mirror image of Muhammad's state of mind. "We encounter highs and lows in the Koran. Whenever the Prophet feels well, the text is edifying, rising to heights of eloquence and admirable articulation. And vice versa, whenever the text is banal and superficial, it testifies to the dejection and gloom of its author."

Muhammad's knowledge was in keeping with his times, writes Soroush, who enumerates "the factual errors in the Koran", which we can only laugh at today: "no one still believes that meteorites are the devil's stones, that the sky has seven ceilings, or that the touch of the devil causes madness."

"Sources of emulation"

The theologian holds forth not only on theoretical issues. He publicises his opinions on current topics almost weekly. And each time, he calls into question either directly or indirectly the rule by the Shia clergy. Soroush advocates instead a strict separation between politics and religion.

Soroush is an absentee figure in Iran, an exile like many other well-known Iranian theologians, for example Mohammad Mojtahed Shabestari, Mohsen Kadivar and Hassan Yussefi Eshkevari. But thanks to the Internet, they all maintain a presence in Iran as well and people there read and hear what they have to say.

All of them are diligent writers and speakers. The Hamburg-based philosopher Shabestari is 80 years old, but still holds regular online seminars. The highly respected theologian also discusses current issues with surprising candour. After the terrorist attacks in Paris, he wrote on his website: "No one can argue that the followers of the IS and their spokesmen have nothing to do with Islam. They fast, they pray and they perform the same religious rituals as you and I. And even their abominable practices are deeply rooted in the Sharia. Only a thorough revision of all Islamic principles can save us from further disasters."

"Their daily bread"

Most of these exceptional exiles were once religious turban-wearers in Iran. Today they call themselves "new religious thinkers" or innovators and have long cast off the customary robe of the mullahs. Nonetheless, according to the prevailing definition, any one of them could be a Grand Ayatollah, a religious "source of emulation". They definitely command the requisite knowledge.

"In particular in Shia teaching, what we have to say is noted very carefully, then discussed or refuted; we are their daily bread," says the Bonn-based theologian Yussefi Eshkevari. "People cannot ignore us because the Internet is today an indispensable teaching aid for the Iranian clergy – an Internet without filters or censorship, because no one dares to censor the Shia teaching institutions," Eshkevari remarks about his exchange of views with scholars in Iran.

The misconception that Iran's mullahs live in seclusion far removed from the world has nothing to do with the reality, says the exiled religious scholar. He demonstrates this by referring to the curricula of the Shia schools: "the students there study Wittgenstein, Freud and Heidegger as well as foreign languages." And, thanks to the Internet, they take note almost without delay of everything the exiles write: "The Islamic Mofid University in Qom, whose students and teachers belong to the clergy, has pledged in particular to address our ideas – or to dispute them," declares Eshkevari, proceeding to list the names of well-known professors at the university with whom he is in constant contact.

Reform comes from outside

But where are the exiles getting their radical and powerful arguments disputing tradition? Does it have something to do with living in the West and exposure to Western ideas? Yes, says Eshkevari: all of those who have come forward over the past 150 years as reformers of the Shia faith have spent time living in Western countries. He counts off dozens of names – Ali Shariati, Mehdi Bazargan, Djamal Aldin Assadabadi. They were all taboo breakers who managed to drive many developments. Eshkevari is therefore among the unwavering optimists who are convinced that Shia Islam will renew itself from the ground up: "And that will be the work of the exiles."

Ali Sadrzadeh

© Iran Journal 2016

Translated from the German by Jennifer Taylor