Arab fear of the "extended arm of Iran"

"The Islamic revolution already controls three capital cities. Very soon they will be followed by Yemen's capital; then Saudi Arabia will be next!"

Does this sound like the victory announcement of a proud field officer on the brink of the successful conclusion of a military campaign? Or does it sound like the gleeful exclamation of someone who will soon be in possession of all the pieces of his puzzle? On 18 September last, the Iranian parliamentarian Alireza Zakani gathered students from the paramilitary organisation known as the Basij around him in the city of Mashhad in north-eastern Iran to explain to them the Iranian offensive in the region.

And lo and behold, only about 20 hours later, the Shia Houthi rebels brought the Yemeni capital Sanaa largely under their control, forced the prime minister to resign and compelled the head of state to sign a peace agreement late that evening. The next day, Zakani was strongly criticised by a lot of newspapers for giving away state secrets and posing a threat to national security. But even so, the 50-year-old parliamentarian from Tehran seems to enjoy the political freedom to do as he pleases without fearing the consequences.

Zakani's biography is his real capital. At just 15, he took part in the war against Iraq. While studying medicine, the disabled veteran was active in the Basiji front line against rival student groups. The silver-tongued delegate sits on important commissions both inside and outside the Iranian parliament, is often present at audiences with the revolutionary leader Ali Khamenei, and as former commander of the Revolutionary Guard, enjoys the trust of the most powerful man in the country. Perhaps this is why he allows himself spectacular public appearances, and believes he can – politically speaking – tell tales out of school whenever he likes.

Alarm bells ringing in the Arab world

But his appearance in Mashhad – in other words his pre-emptive victory announcement regarding Yemen – had devastating foreign-policy consequences for Iran. Following the victory by the Shia Houthis, a wave of anti-Iranian commentary washed through the Arab media. "Yemen under Iranian control" read the headlines in most newspapers, all of them quoting Zakani's speech, in which he predicted the rebels' victory and set his sights on Saudi Arabia. After Baghdad, Damascus and Beirut, Sanaa was the fourth capital city in the Arab world that would soon be dancing to Iran's tune, wrote a commentator for the Al-Jazeera website, drawing a parallel between the Shia Houthi rebels in Yemen and Hezbollah in Lebanon, adding that it was common knowledge that both were the extended arm of Iran.

Other newspapers, like the Lebanese "Al-Hayat", focused their commentary on Zakani himself and the part of his speech in which he prophesied a similar development in Saudi Arabia. None of this commentary and analysis painted Zakani as a maverick or a radical with an inflated image of his importance. Instead they expressed the opinion that Zakani is someone who says straight out what the important men in the Iranian apparatus of power are thinking and doing, wrote one commentator on the Al-Arabiya website.

As if wanting to confirm what the Arab commentators had said, radical Iranian newspapers and websites like "Kayhan" and Fars have since been celebrating the "Iranian victory" in Yemen, quoting the most important military officers in the country. Three days after the transfer of power in Sanaa, Fars News (the agency with the best secret service contacts in the Islamic Republic) published an interview with Ali Hadji Zadeh, the commander of the air and ground units of the Revolutionary Guard.

Just as Zakani boasted of the impending victory of the allies in Yemen, Hadji Zadeh also revealed interesting details about how the Revolutionary Guard is operating across the whole region. According to him, General Qassem Soleimani prevented the Iraqi city of Erbil from falling into the hands of the IS terrorists with only 70 men. Zadeh praised the "great battle tactics of the commander of the Quds brigades", who has long been hailed by some Iranian media as a hero with supernatural abilities. It is not the USA and its coalition partners, but Soleimani and his allies in Iraq who could really stop the IS terrorists there, predicted Hadji Zadeh.

A firm friendship

This may be exaggerated hero worship, but recent BBC reports confirm that Soleimani's operation in Iraq is proving successful, meaning that he is now revered there as well and has the support of reliable partners in Iraq. A TV report shows the political situation in the small Iraqi town of Suleiman Bek, around 90 kilometres north of Tikrit. It is the afternoon of 9 September, shortly after the liberation of the Shia-majority town of Amerli, following an 80-day blockade by IS terrorists.

A car drives by; in it are two generals on their way back from a battle their forces have won. But for the people who have gathered around the BBC reporter in the town, these men — Qassem Soleimani and Hadi al-Amiri — are living legends, famous heroes, who have exerted a decisive influence on all the wars and civil wars in this region for the last 30 years. And if anyone can put a stop to the IS murderers' activities, then the people present here believe it can only be these two tireless warriors: the Iranian Soleimani and the Iraqi Amiri.

The two 60-year-olds have known each other for more than 30 years, since the start of the Iran-Iraq war, when the Iraqi Amiri, at the time a young Shia activist, escaped Saddam's henchmen and fled to Iran by a round-about route. That was the beginning of a firm friendship between two men whose work and whose calling have become revolution and war.

Iran in Baghdad's centre of power

Amiri is now the Iraqi transport minister. Amiri was originally due become defence minister or minister of the interior (in other words, to take up a post with responsibility for security), but the Sunnis in the Baghdad parliament were vehemently opposed to this plan because Amiri is the head of a 30,000-strong militia, the Badr brigades.

In addition to this, the appointment would have meant putting someone who was practically an Iranian in charge of Iraq's security forces, or so the Iraqi Sunnis feared. Amiri may have been born in the Iraqi province of Diyala, but he spent 30 years with the Revolutionary Guard in Iran, and built up the Badr brigades there together with other members of the Iraqi opposition, who then returned to Iraq after Saddam was toppled.

Amiri's Iranian wife still lives with their three children in the district of Tehran principally inhabited by the commanders of the Revolutionary Guard. But it is not just their life histories that bind together the Iraqi Amiri and the Iranian Soleimani. The two men are also wholly united in their political and religious convictions. In a TV interview a year ago, Amiri said: "I believe in the principle of velayat-e faqih, the absolute rule of the supreme jurist, as it currently exists in Iran."

A double-edged sword

Biographies like this, which are not a rarity in Iraq's corridors of power, have contributed to the alienation of many Iraqi Sunnis from the central government in Baghdad. There are many reasons why a strong nation state could not be built after the overthrow of Saddam. But the deciding factor may well have been the control of the Iraqi security apparatus by the Badr brigades and dozens of other Shia militias. And when those in power in Iran speak of their Iraqi allies, it is these militias – both inside and outside the apparatus of state – that they are talking about. This is why many Iraqis have mixed feelings about the Iranian campaign against IS. As one Al Arabiya commentator put it, it's a double-edged sword.

The BBC reporter reached a similar conclusion after the liberation of Amerli. After Soleimani and Amiri, revered as war heroes by the Shias present there, had departed, the reporter carried on researching, recording the enthusiasm for the Iranian assistance, registering the number and type of Iranian personnel and arms there, and finally driving on to the city of Kirkuk. There she met a group of frightened Kurds and Shias who were hiding from the "Iranian helpers" and their Iraqi allies.

Among them was the Shia village leader, who told the reporter something very frightening. The experienced old man from near the town of Amerli – as a Shia, he had once been an avid supporter of the Islamic Revolution in Iran – explained to the reporter that there was an increasing number of young Shia militia men in the region, who were often more dangerous and brutal than in the past. Even more dangerous than the Badr brigades, who were known for their brutality? That's certainly saying something in these times, when there is an absence of any kind of state authority in Iraq.

The reformers and moderates in Iran must know what kind of future awaits Iraq if the alienation of the majority of Iraqis from their state and the rule of the militias continues. Without national reconciliation and the integration of all powers, the failure of the reconciliation process is guaranteed, as Iran's president Hassan Rouhani recently warned the new Iraqi prime minister, Haider al-Abadi, on the fringes of a UN general assembly.

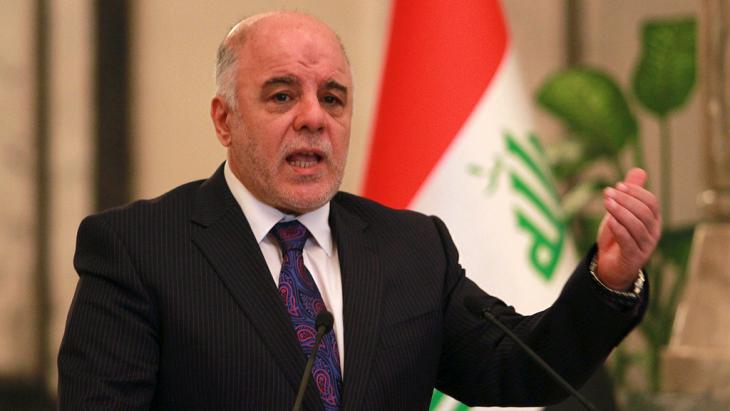

But the path to reconciliation is clearly stonier than many first thought. The new Iraqi prime minister is now facing his first governmental crisis. Even his new candidates for the offices of minister of the interior and defence minister did not receive a majority at the last session of parliament. The Shia al-Abadi thus remains, for the time being, the supreme commander in a regional conflict on many fronts.

Ali Sadrzadeh

© Qantara.de 2014

Translated from the German by Ruth Martin