The curse of religiosity

Daesh did not emerge in a vacuum; rather, it is the product of a culture of social, religious and political control that has governed the public arena for the last fifty years or so. It developed amid a climate of swift decline brought about by the failure of the state in the Arab region, combined with non-stop wars and military interventions from outside.

The main contributing factor has been a conservative religious and social culture which hijacked mosques, schools and the media, establishing a strict religious regime for determining right and wrong in the process. This regime thus decides how an individual is regarded by society; indeed, the status and respect which he, or indeed, she commands is dictated by religious and devotional hierarchies and priorities. Focusing on this is not intended to detract from the considerable influence of other factors, specifically the failure of the state and the interference of foreign powers, but the constraints of this piece do not allow for a discussion of every aspect.

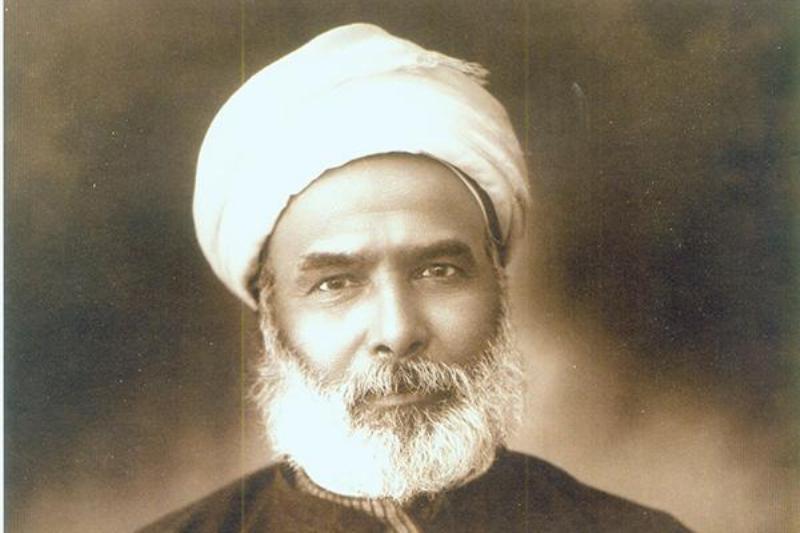

The collective religious culture has acquiesced to the manufacture of an undeniably "latent Daesh-isation" in society, which has gradually taken hold of much of public life. The first roots of this phenomenon can be traced back to the collapse of the progressive reform movements led by Jamal al-Din al-Afghani, Muhammad Abduh and Abd al-Rahman al-Kawakibi at the hands of the Salafist rhetoric and narrow-mindedness of Hassan al-Banna and, subsequently, Sayyid Qutb and the wider Salafi movement. Yet this "Daesh-isation" was consolidated far away from the official political establishment.

The religious transformation of public life

The short of it is that political regimes and Islamist opposition movements have competed against each other to bring about the religious transformation of public life in most countries, albeit in varying degrees. The most obvious example of this struggle in terms of impact and destruction is the battle for political legitimacy and the religious transformation of the media and educational curricula. This has led to religious rhetoric dominating the discourse. As a result, it is religion that has become the prime organiser of collective thought, leaving an indelible mark on the many laws introduced to frame public practices, morals and conventions.

The predominance of religious discourse has had a distinctly practical impact. These days, a person living in an Arab country has two nominal and frequently contradictory identities: the first, a religious one, defined by the degree of religiosity and devotion and the second, a legal one, defining the individual as a citizen in accordance with the constitution. The first identity prevails over the second to a remarkable degree, so much so that the "religious" persona has become the standard model and is tacitly considered "better" than the one which is "not religious".

Were the difference restricted to an individual′s actual beliefs, there would be no cause for concern. Yet, in elevating "religiosity" – taking it out of the realm of individual practice and making it a social and legal norm – the gap has widened to such an extent that it has squeezed the individual′s legal status. Two diametrically opposed viewpoints emerge.

The religious rationale of the first identity contradicts the notion of the modern state, which is based on the principle that every citizen is equal in the eyes of the constitution, with both rights and responsibilities, and without regard to a person′s religious affiliation. Indeed, in the second identity, each individual is defined fundamentally as a "citizen".

No intrinsic link between moral behaviour and religiosity

Those who advocate religious movements worldwide assert that adherence to faith provides the foundation for superior morals, multiplies good and curbs evil. But this argument is incoherent, both theoretically and statistically. For example, Arab and Muslim countries are considered to be some of the most religious societies in the world, alongside those in sub-Saharan Africa, yet many of them – such as Afghanistan, Iran and Egypt – surpass the world in terms of bad practice: sexual harassment of women, lack of respect for public order and cleanliness, for instance. Indeed, many countries with a low religiosity ratio and a high atheism ratio have lesser rates of sexual harassment and greater respect for order and cleanliness. Thus, there is no intrinsic link between moral behaviour and religiosity that these advocates like to claim.

All of this presents a body of facts and arguments which ought to make us sick with worry: first, we need to get rid of the moral tyranny of a powerful and conditional relationship between religiosity and loyalty to one′s country, as has become popular in the collective mind since the expansion of Islamist movements across the region (and which has been indirectly reinforced by the official discourse).

Religion has been variously used to undermine and call into question citizens′ loyalty, morality and civic ethos. It has also been used to throw doubt on the sincerity of the non-religious, questioning their ability to uphold decent ethical standards, with the implication that such values are the sole preserve of the religious. The intention is not just to show that the non-religious have no loyalty and are traitors acting as agents of the West and the outside world, but more sinisterly that they are not citizens with full rights.

The questions and challenges we all face, whether we′re in power, in opposition or in society at large, are embodied in the notion of absolute equality between citizens, regardless of all else. This is still the presumption on which all civil states are based, i.e. whether citizens are religious or not, the state grants them rights and expects them to fulfil their duties in accordance with the constitution.

A civil state which is predicated upon the principle of equality should protect the rights of its citizens, thereby allowing them to enjoy their personal, cultural, not to mention political freedoms. Such a state should provide a healthy environment for a normal life, free of oppression. It is pointless to resort to the notoriously vexatious notion that there are limits to "freedom" and that it′s not absolute, since that is clearly social conjecture. After all, even in the most progressive countries in the West, a person isn′t allowed to practise his or her individual freedom by venturing out naked into the street.

Khaled Hroub

© Qantara.de 2017

Translated from the Arabic by Chris Somes-Charlton

Khaled Hroub is a renowned writer and researcher on Arabic and Islamic issues.