In Gandhi's footsteps

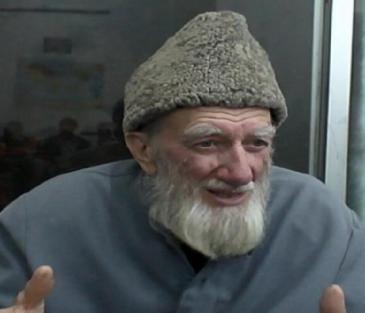

The most prominent advocate of consistent non-violence from Islamic sources is the Syrian scholar Sheikh Jawdat Said. Born in 1931, Said earned a degree from Al- Azhar University in Cairo in 1957. During his time in Egypt he witnessed the escalating tensions between the Muslim Brotherhood and the Nasser government. And he also observed how the increasing militancy of the Muslim Brothers gave Nasser a pretext for even more state repression.

His most important book, "The Doctrine of the First Son of Adam: The Problem of Violence in the Islamic Action" was published in 1964 and was a direct retort to Sayyid Qutb, one of the founders of militant Islam. Said does not deny that the Koran contains the right to self-defence. Nevertheless the scholar, who is sometimes referred to as the "Arab Gandhi", pleads for a complete abandonment of violence. He views the democratic state governed by the rule of law as the most suitable political framework for a peaceful solution of conflicts.

Said has published numerous books, which are widely discussed in the Arab world. They are little known in the West, however, even though some of his works have been translated into English. In his native Syria, Jawdat Said has been involved in the democratic opposition, but there as well, he has a low profile outside of intellectual circles. In 2005, he joined other opposition figures in signing the Damascus Declaration.

Model for the nonviolent protest against Assad

"For a long time, he was barely known in Syria, but at the beginning of the demonstrations against Assad in March 2011, passages from his works suddenly appeared on banners," reports the Islamic scholar Muhammad Sameer Murtaza, who studies approaches to nonviolence in Islam on behalf of the German foundation "Stiftung Welthethos" (Foundation for a Global Ethic).

Murtaza says that Said repeatedly admonished the demonstrators to express their concerns peacefully and not to respond to the attacks of the regime with counter-violence. After the Syrian revolution had become an armed conflict and Said's house in the village of Bir Ajam was destroyed, the scholar fled to Turkey, where he now lives in Istanbul.

In India, Maulana Wahiduddin Khan (b.1925 in the state of Uttar Pradesh) has developed an Islamic theology of peace based on Sufi sources, for which he has received numerous official awards. The founder of the "Centre for Peace and Spirituality" in New Delhi repeatedly emphasises that non-violence today represents the only acceptable option for Muslims. Khan has however sparked some resentment among Muslims with his statements on the Middle East conflict, where he sides unequivocally with the Israelis. On the whole, his theology of peace seems less cogent than the approach taken by Jawdat Said.

Similar approaches have also been endorsed by the Shia cleric Mohammad Al-Shirazi (1928–2001) in Iran and Asghar Ali Engineer (1939–2013) in India.

Non-violent resistance in Palestine

But it is not only theorists who have dealt with this subject; there are also concrete practical examples of nonviolent civil disobedience, for example in the West Bank. The Palestinian farmers in the village of Bi'lin (and other villages in the region) have been fighting for their rights for years by means of peaceful sit-ins and protests, trying to demonstrate a way to escape the endless cycle of violence and counter-violence.

They have never heard of Jawdat Said. Nor have they let the attacks by the Israeli army dissuade them from their peaceful protest. The only problem is that the farmers of Ni'lin attract much less media attention than suicide bombers and terrorists.

The Egyptian Mohammed Abu-Nimer argues in favour of also devoting greater scholarly attention to such examples of peaceful civil resistance among Muslims. To date, the focus has been too one-sided, grappling only with the question of why there is violence in the name of Islam. Abu-Nimer is not a theologian but instead director of the "Peacebuilding and Development Institute" at the American University in Washington, D.C.

The conflict researcher has presented a concept for working toward peace in Islam, identifying Islamic principles such as the value of life and the pursuit of understanding and harmony and deriving from them an argument for why non-violence must be considered a core principle of Islam. There are by all means resources available in the sacred texts and in the Islamic tradition that could be mobilised for the peaceful resolution of conflicts, says Abu-Nimer. These resources for non-violent reconciliation of divergent interests have been neglected far too long, he adds.

Religious prohibition on violence

According to Abu-Nimer, highlighting how the Koran allows the use of force in self-defence is no longer helpful for today's problems. "Times have changed and the use of violence to settle differences and to spread the faith is no longer countenanced by the religion," he writes.

Traditional protective mechanisms specified in the Koran, for example the distinction between combatants and civilians, have no meaning in the 21st century. Asymmetrical wars and remote-controlled drones, not to mention nuclear weapons, make such a distinction obsolete.

Consistent advocates of nonviolence are still a little-known minority among Muslims. In a five-year project initiated by the Stiftung Welthethos, which was founded by the Catholic theologian Hans Küng, the Islamic scholar Muhammad Sameer Murtaza intends to research such approaches more thoroughly and make them more widely known in the Muslim community. It is hoped that these ideas, new for many, can contribute to reducing the social and political tensions that currently threaten to tear Muslim communities apart.

By Claudia Mende

© Qantara.de 2015

Translated by Jennifer Taylor