How the brain processes German and Arabic

A native speaker of Arabic has to listen carefully during a conversation: Does the other person mean kitabun (كتاب) or katib (كاتب)? "Book" or "writer"? Both words are based on the same language root k-t-b ( ب - ت - ك), which is very common in Arabic.

A native German speaker, on the other hand, has to focus mainly on sentence structure: "Leihst du dir das Buch von deinem Lieblingsschriftsteller aus?" – in English: 'Are you borrowing a book by your favourite author?' In German, some verbs like ausleihen ('borrow') split, with elements being positioned separately within the sentence. The Arabic and German languages are very different. But can these differences also be detected in the brains of native speakers?

Scientists from the Max Planck Institute for Human Cognitive and Brain Sciences in Leipzig decided to investigate further. The team, led by doctoral student and primary author Xuehu Wei, conducted a study involving 47 native speakers of Arabic and 47 native speakers of German.

When selecting the test subjects, the researchers ensured that candidates had grown up in a monolingual environment and thus had only one native language. In addition to their first language, the subjects had a smattering of English.

Brain scans reveal differences between native speakers

The team of scientists asked the participants to undergo a magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) scan. Not only do such scans produce high-resolution images of the brain, but they also reveal information about how the nerve fibres are connected. With the help of this data, the researchers were then able to calculate how strongly the individual language regions were wired together.

"The result was very surprising, We had always assumed language was universal," says Alfred Anwander, a researcher with the department of Neuropsychology at the Max Planck Institute in Leipzig and co-author of the study. "We used to think that where a language is processed in the brain and even how strong the connections are between different parts of the brain was the same for all languages."

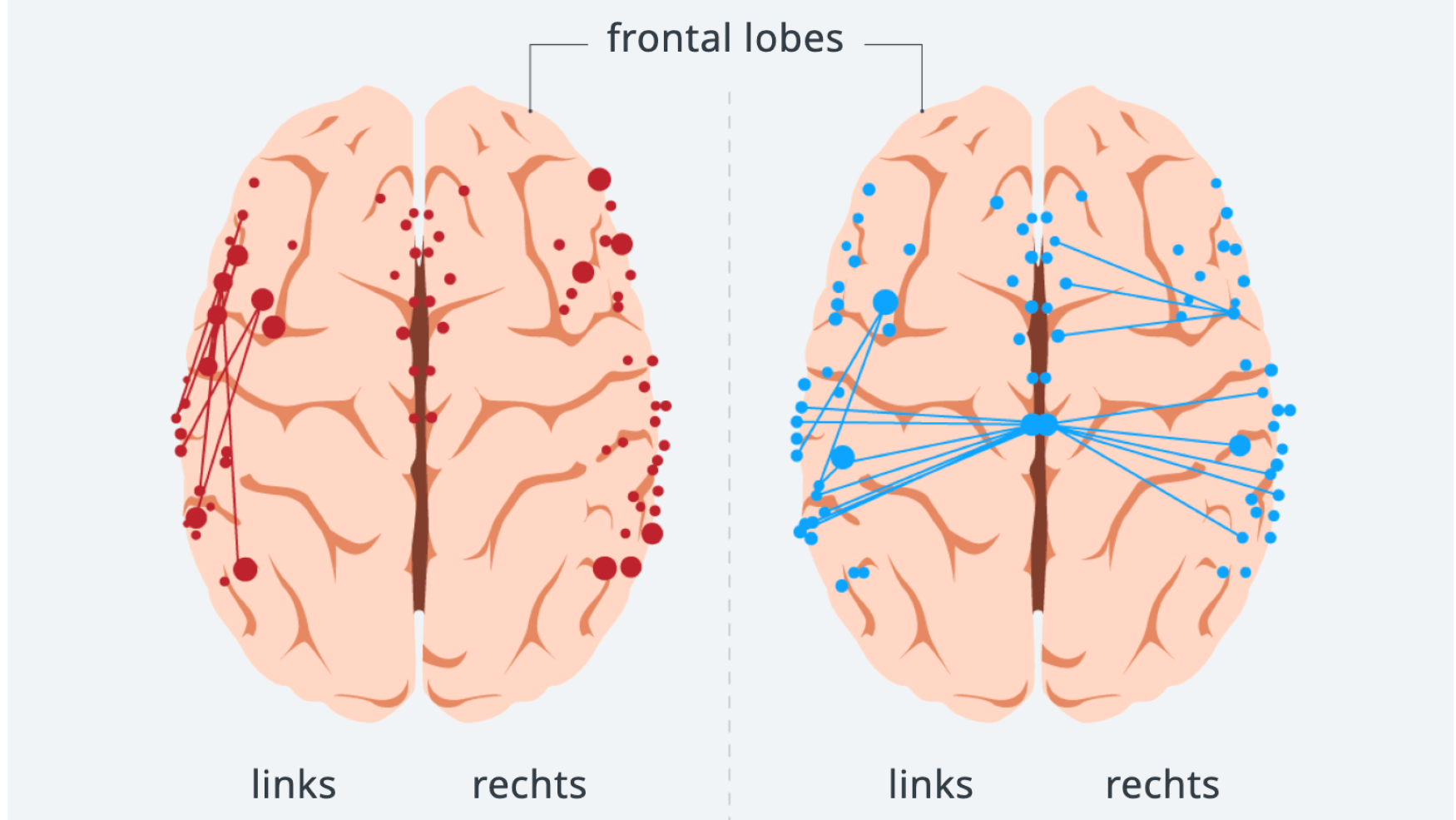

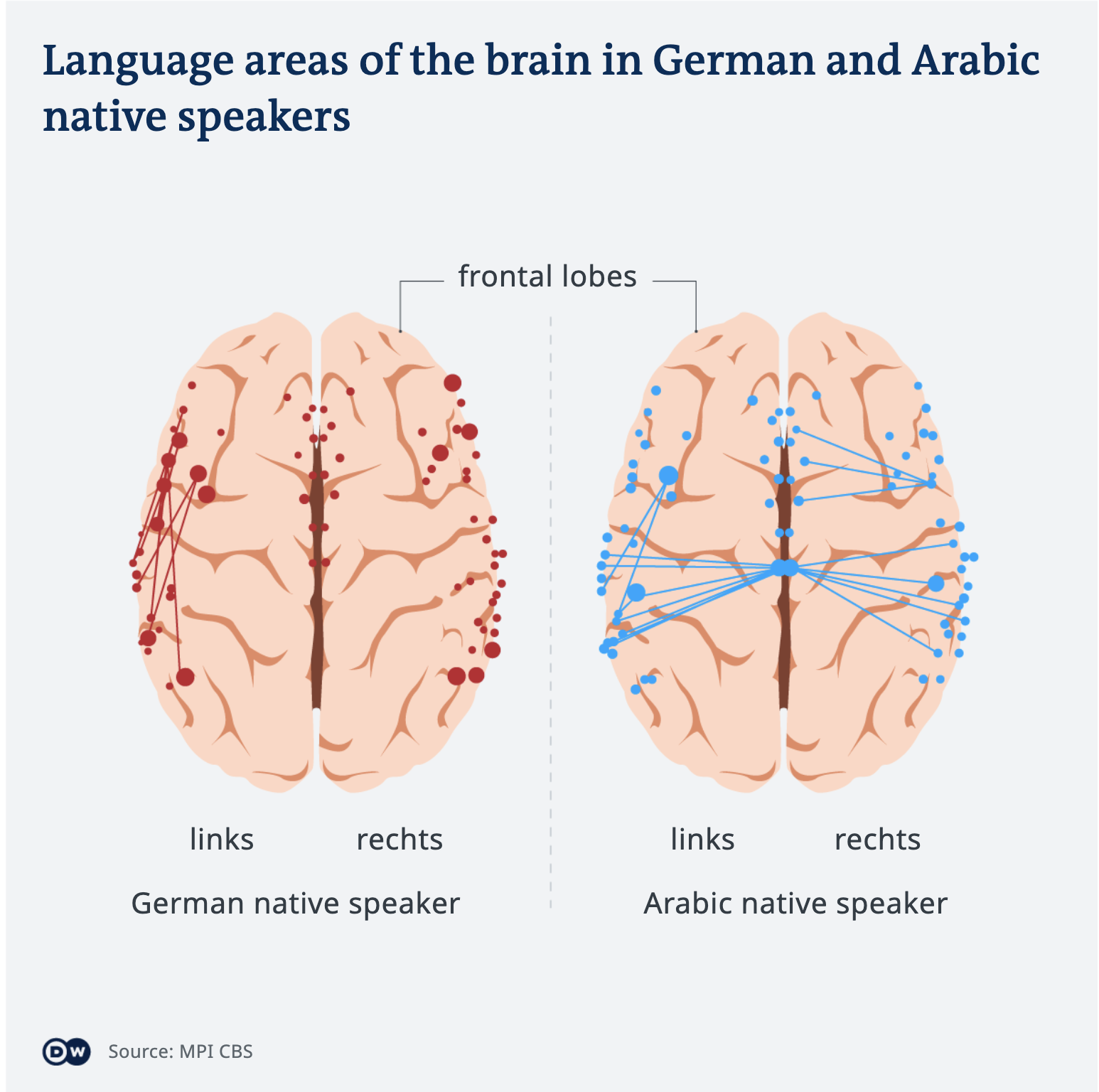

In native speakers of Arabic, however, the research team discovered more pronounced connections between the left and right hemispheres of the brain. There was also a stronger connection between the lateral lobes of the cerebrum, called the temporal lobe, extending towards the central section, known as the parietal lobe.

Language centres for pronunciation and meaning

The discovery was plausible: these regions of the brain are responsible for processing the pronunciation and meaning of spoken language. A native speaker of Arabic must concentrate precisely on how the word is pronounced and what meaning it has as a result: did his conversation partner say "kitabun" (book) or "katib" (writer)?

In the native speakers of German, the scientists found stronger connections in the left hemisphere of the brain and towards the frontal lobe in the frontal area of the brain. This can also be explained by the nature of the German language since these regions are responsible for processing sentence structure. As a result, complicated sentences, with multiple clauses, are easily understood by native speakers of German.

"Our study provides new insights into how the brain adapts to cognitive demands – our structural linguistic network is thus shaped by our native language," summarises co-author Anwander.

Valuable knowledge concerning the way language is processed

According to the researchers, it is important to emphasise that these different circuitries mean neither advantages nor disadvantages for speakers. "The wiring is simply different, not better or worse," says Anwander.

Knowledge of the differently wired speech centres, on the other hand, does imply advantages for native speakers of either language. For example, it could improve the treatment of stroke patients. Some stroke sufferers are affected by a speech disorder called aphasia. Different therapy approaches could be developed for speakers of different languages, enabling patients to learn to speak again more quickly.

"What's more, it will be very exciting to extend the study to more languages," says Anwander. In another study, the Max Planck researchers have examined native speakers of German, English and Chinese. The results are still pending.

It remains to be seen whether and how other native languages shape the brain. A larger-scale study of native speakers of German and Arabic would also be helpful to confirm the results.

New methods for foreign language learning

In a second phase of the current study, researchers will analyse what happens to the brains of Arabic speakers when learning German. "We are curious to see how the network changes when learning a new language," says Anwander.

Ultimately, the findings could also be used to improve methods for learning foreign languages. Depending on the learner type and native language, different strategies could be developed to make it easier to learn German, for example. However, a lot of research is still needed for that to happen. "We are still a long way from individual learning strategies based on a brain scan," says the researcher. Until then, language students should stick to their vocabulary notebooks.

Katrin Ewert

© Deutsche Welle 2023