The eighth wonder of the world?

Contrary to common belief, Libya′s riches lie not in oil, but in water. The world′s biggest reservoirs of fossil freshwater lie below its desert. Through an extensive pipeline system, these aquifers provide the country with water for consumption and agriculture. The so-called ″Great Man-Made River″ is the world′s largest irrigation project.

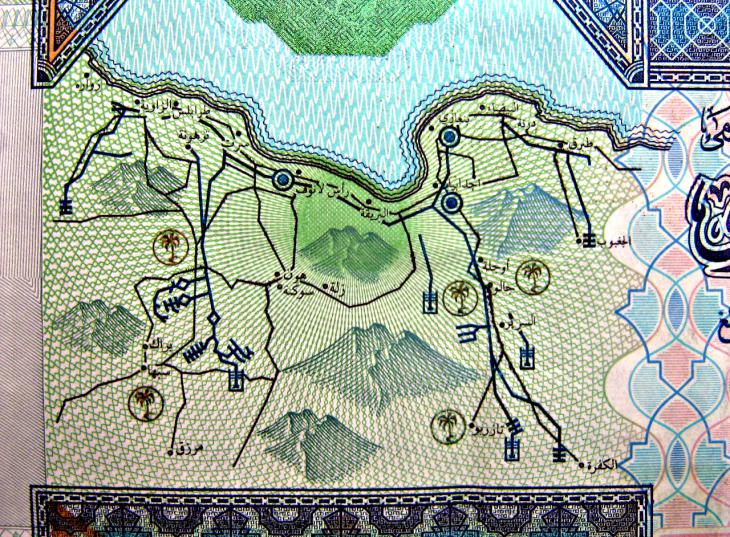

Libya′s Great Man-Made River (GMMR) currently transports almost 2.5 million cubic metres of water daily. Piped through an underground network from the Nubian Sandstone Aquifer System in the Great Sahara desert to the coastal urban centres, including Tripoli and Benghazi, the water covers a distance of up to 1,600 kilometres. The GMMR currently provides 70 % of all freshwater used in Libya.

Apart from the green and fertile strip that runs along the Mediterranean coast, Libya is mainly desert with a few scattered oases. Rain falls on only five percent of its surface. There is not a single river that would carry water the whole year round and water scarcity has always been a huge problem.

The solution was found by chance when oil companies were prospecting for crude in the Libyan desert in the 1950s. ″They discovered basins containing huge amounts of water,″ says geologist Zakaria Al-Keep. ″It was fossil freshwater that had been stored underground for thousands of years.″

Libyan researchers were thrilled. They had been assessing various ways of obtaining drinking water. Options included the desalination of seawater or importing water from Europe by pipeline or ships. Now another possibility was to exploit fossil water resources from four underground desert basins: Sarir and Kufra in the south-east and Murzuq and Jabal Hasawanain in the south-west. The idea of the GMMR was born.

Gaddafi′s prestige project

On 28 August 1984, Muammar Gaddafi, the dictator who was toppled and killed in 2011, laid the foundation stone in Sarir. The plan was to drill 1,350 wells across the four basins.

Many of those wells are now operational. Most are more than 500 metres deep. They are connected to the coast by pre-stressed concrete cylinder pipes. Each pipe is seven meters long; the diameter is four meters. In total, more than 4,000 kilometres of pipeline have been built. They deliver over 6 million cubic meters of water per day. An additional 2,000 kilometres are planned.

The GMMR is the world′s biggest irrigation project ever. In 1999, UNESCO awarded Libya a prize for notable scientific research regarding the use of water in desert areas.

The infrastructure is owned by the GMMR Project Authority. The primary contractor for the first phases in the Gaddafi era was the Dong Ah Consortium. Currently, the main contractor is Al Nahr. Both are domestic construction companies. Korean and Australian firms have supplied some technical parts.

So far, Libya has managed to build the GMMR without financial support from other countries or loans from banks. Taxes on tobacco and fuel contributed to mobilise money, while oil revenues naturally helped too. So far the GMMR has cost upward of $36 billion. By 2007, three out of five project phases had been implemented, providing all major cities with water. Phase four has made good progress, but further construction was put on hold because of the revolution in 2011 and the on-going civil war since.

Impact on the environment unclear

Thanks to the massive freshwater flows from the GMMR, agriculture has become feasible also in desert areas. The government invested in seven big agricultural schemes. One is south of Tripoli, the capital. This project in the Jafara plains consists of 3,300 hectares, divided into 665 farms. These farms produce different kinds of citrus fruits, wheat, barley and vegetables. There were plans to plant millions of palm trees farther south, but fighting in recent years disrupted developments.

Libyan law foresees that an environmental impact assessment is generally carried out before starting a major project. In the case of the GMMR, however, no assessment was ever conducted, as Khalifa Elawej, an advisor to the General Board of Environment, points out. The political decision to start was taken in view of an ″acute shortage of water″. At the time, the cost of fossil water was only one tenth of that of desalinated water. To date, the environmental impact assessment is still outstanding.

According to Elawej, it is impossible to give accurate report of the environmental effects, since no relevant data currently exists. This would entail a huge amount of research. Elawej regards the positive effects of the project as follows:

- The GMMR has helped expand the green areas in the north and west of the country, preventing further desertification.

- The green areas contribute to tempering the weather.

- Traditional water resources in the north have been spared as people can now rely on GMMR water instead.

- Agricultural production has increased.

According to Elawej, the negative effects include:

- The desert environment of the areas where the fossil water is taken from may be changing.

- The pipeline network itself may affect the environment.

- Some of the water is stored in open pools, with evaporation leading to salinisation. Salinity of the GMMR water is high according to international standards, though it is not as bad as in the north′s traditional wells, which are affected by an influx of seawater.

- Since most – and perhaps all – of the fossil water is not renewable, a finite resource is being used.

Over the course of the civil war, the GMMR has suffered severe damage. During the revolution in 2011, NATO airplanes bombed water ducts in Brega. They also targeted a pipe factory, possibly in order to cut off Gaddafi′s forces from their water supply. More recently, there have been acts of sabotage in the south. In March 2017, the GMMR administration issued a warning that repeated assaults on wells at Jabal Hasawna might completely stop the water flow to Tripoli and other north-western cities.

Moutaz Ali

© Development and Cooperation | D+C 2017

Moutaz Ali is a journalist and lives in Tripoli, Libya.