Acknowledging reality

It is not known how many women abort illegally in Morocco, as no studies on the issue have been carried out to date. There are, however, estimates based on random samples and empirical data from the World Health Organisation (WHO): these suggest that at least 200,000 illegal abortions are carried out every year in Morocco.

As illegal abortions carried out by doctors are expensive – a termination costs between €200 and €600 – it is thought that one in every five women seeking an abortion resorts to more risky procedures, often with dramatic consequences. An average 7,000 Moroccan women die each year as a direct or indirect result of unprofessionally conducted terminations.

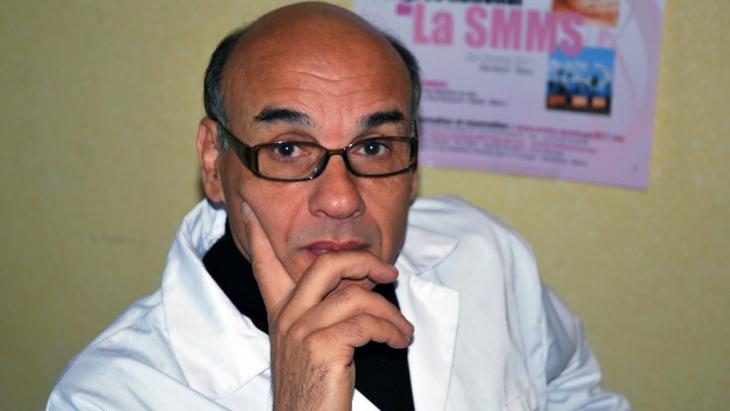

Chafik Chraibi is a senior consultant at a major state-run maternity hospital in Rabat. Every day he sees patients suffering the consequences of illegally and unprofessionally conducted abortions. "They have terrible bleeding, severe infections, genital injuries and contamination. Sometimes it's too late for us to save these women," Chraibi tells Qantara.de, adding "I was appalled, I wanted to do something."

The law is tough on doctors

Back in the year 2008, Chraibi and a small group of colleagues founded the Association for the Fight Against Clandestine Abortion (AMLAC). The organisation plays a leading role in the current debate about the liberalisation of Morocco's abortion law.

If abortion was legal in Morocco, many lives could be saved and many complications avoided. But thus far, doctors in Morocco have only been allowed to carry out a termination in one particular scenario: if the physical health of the mother is in danger. Anyone breaking the law risked up to five years in prison, with the judicial system rigorously pursuing this line. There have been repeated indictments; sometimes, harsh sentences have been handed down to gynaecologists.

Even a public statement was potentially risky: in late January 2015, Chafik Chraibi was suspended from his duties at the maternity hospital in Rabat because he had helped a French television crew film a reportage on illegal abortions in Morocco. Chraibi had to take the matter to court before the suspension was revoked.

Supported by the monarchy

This makes it all the more surprising that advocates of a liberalisation of the abortion law are now receiving backing from the highest office in the land: on 16 March 2015, King Mohammed VI summoned the Ministers for Justice, Religious Affairs and Human Rights to his palace and commissioned them to come up with the first draft of a new law within a month. They were told that the consultations were to involve academics, representatives of civil society and media representatives.

The draft framework for the legislative reform has been ready for consideration since 15 May 2015. In future, the royal advisers recommend not just allowing for an abortion when the life of the mother is in danger, but also when her health is at risk, in the case of a serious birth defect or untreatable illnesses affecting the foetus, and in cases of rape or incest.

Moroccan women's organisations have been critical of the first draft. On 25 May 2015, a broad-based coalition of Moroccan women's groups calling itself "Le Printemps de la Dignite" (The Springtime of Dignity) made a public announcement welcoming the new openness on the issue of abortion.

However, it went on to say that the draft reform evades the real issue: "The indications referred to only concern a small minority of women in need. In addition, abortion is treated as a religious, moral question. But this is actually about public health," said the coalition's statement.

Hafida Elbaz, the manager of "Solidarite Feminine", an organisation for single mothers, is also disappointed: "It was clear that this advisory committee would proceed very cautiously. But we didn't expect the draft to be so restrictive. Questions such as whether the women concerned are underage or mentally disabled are not mentioned at all. We are disappointed," says Elbaz.

Calls to decriminalise abortion

Secular Moroccan women's rights activists are demanding a general decriminalisation of abortion on the basis of universal human rights and female self-determination. But for many very devout Moroccans, the central issue is not the human rights of the woman, but the protection of the unborn child, says Islam scholar Nils Fischer: "The Koran contains a prohibition on killing, and the protection of life is a central concept in Islam."

While Fischer concedes that the Koran does not say anything explicitly on the issue of pregnancy termination, he points out that the Sunnah and Islamic medical literature contain many statements on the early stages of human life in the womb: "Some authors believe that the embryo gains its soul within 40 days, others believe that the soul enters the embryo after 120 days. These are the two key standpoints," says Fischer.

Until the early twentieth century, teachings to the effect that this ensoulment occurred in stages meant that Islamic legal scholars were able to allow a termination in specific circumstances. These days, many view the fertilisation of the egg and its implantation in the womb as the beginning of life and therefore argue for a total ban on abortion.

But policymakers are not obliged to embrace the views of Islamic theologians. Tunisia, for example, has been allowing abortions in public hospitals since the 1970s, at almost no cost. The ruling Tunisian elites at the time were more concerned with demographic policy – religious viewpoints were considered at a later date.

Reforms that send out a socio-political message

The political co-ordinates are somewhat different in Morocco, although here too, the emotive issue of abortion is used to conduct power politics. Observers of the political landscape are drawing parallels with the reform of the family code ("mudawwana") in the year 2004, which abolished the principle of obedience and finally gave Moroccan women the right to file for divorce themselves.

At the time, King Mohammed VI was not only concerned with the emancipation of women, but also with sending a political signal to modernist elites at home and abroad. In addition, the move was aimed at putting the Islamist opposition in its place.

Local and regional elections are due to be held in Morocco in September. It is the will of the king that the largest Islamist party, the PJD, which has more than a quarter of seats in parliament and puts up the head of government, should not further consolidate its influence. But the PJD could score points in the election campaign with emotive topics such as abortion. In order to prevent this, it is opportune for the King to stake his own claim to sensitive political issues.

"Prevention is paramount"

The new abortion law is due to be published by the end of the year. At the present moment, many details are unknown. "How legislators define the term health will be decisive," Chafik Chraibi told Qantara.de.

The WHO understands "health" not just in the physical sense, but also as a measure of psychological and social wellbeing. "If we manage to agree on this far-reaching definition, then we've won," says the doctor.

Aside from the issue of how terms are defined, it is likely that the debate will change the nation. "Moroccan society is going through a period of change. Many young people do of course have sex outside marriage. Essentially, prevention is paramount. But unfortunately, sex education and information about contraception are rare," says Chraibi.

But it doesn't end there: extramarital sex is criminalised by the law and punished as prostitution. Children conceived outside marriage are largely without rights and are socially stigmatised. "If we had fewer taboos and more rights for unmarried mothers and their children, then in many cases abortion wouldn't be an issue," says Hafida Elbaz from the women's organisation "Solidarite Feminine".

Acknowledging the reality will also be a key feature of the Moroccan abortion debate over the coming months.

Martina Sabra

© Qantara.de 2015

Translated from the German by Nina Coon