A whispered history

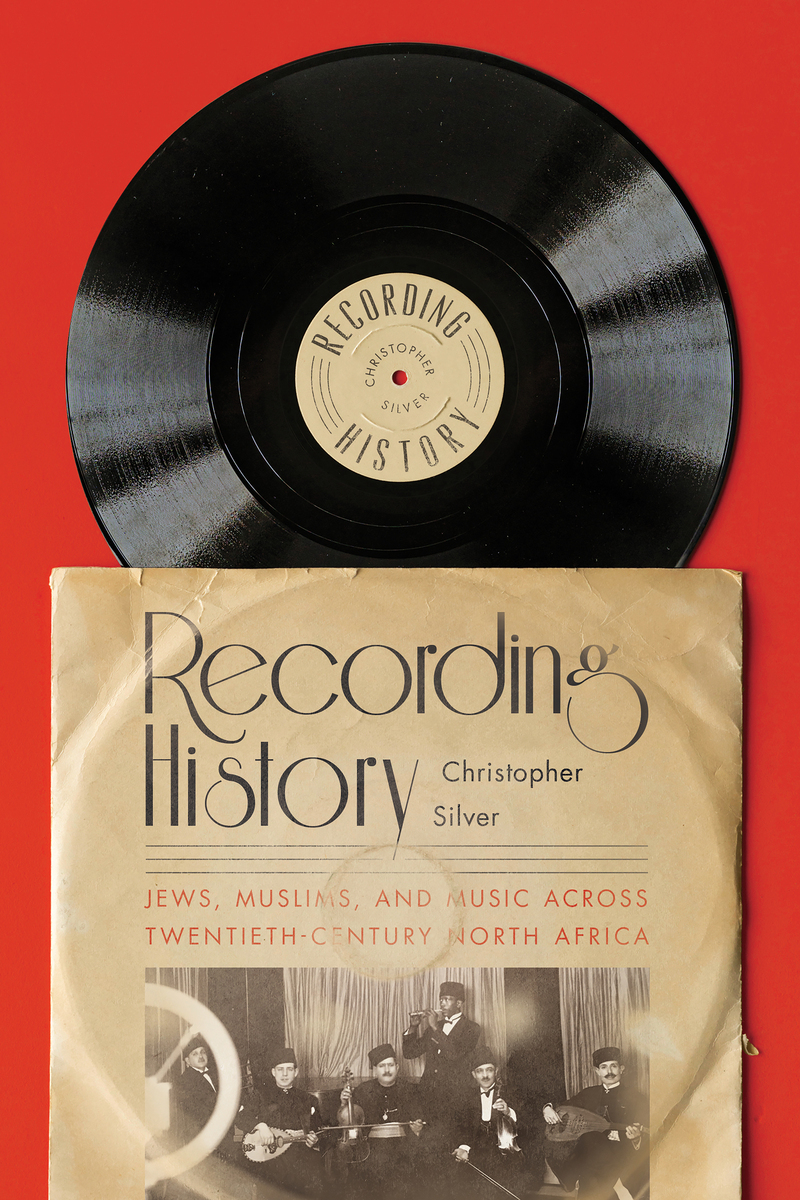

What made you want to write this book? Did the website “Gharamophone.com” predate or arise out of it?

Christopher Silver: The book definitely came as a later step in a longer process. Appropriately, this story began for me in a record store in Casablanca by the name of Le Comptoir Marocain de Distribution de Disques. I entered Le Comptoir in 2009 and when I exited, my life had changed. It was in that record store that I began to understand that recording specifically was an entire world and it involved, in addition to large, transnational audiences, many different players: individual artists, vocalists, instrumentalists, sound engineers, talent scouts, label representatives, distributors, and more.

Beyond nation-state boundaries

When I was in Le Comptoir, the proprietor gave me a sonic tour of what he had on offer. I was blown away by the music. I was intrigued by the fact that the proprietor kept on making reference to just how many of the artists that we were listening to were Jewish. It was something I noted at the time. It almost felt like someone was whispering history to me. Liking what I heard, I bought a number of records. I spent time with these sound documents. I started to make connections between record labels, artists, composers and other details. From there, I grew my collection.

I quickly realised that it was difficult to confine this music within the boundaries of the nation-state. The records I discovered in Casablanca in 2009 were, of course, vinyl, dating from the second half of the twentieth century. But I soon became fascinated by the world that preceded this technology, in the origins of the recording industry in the nineteenth century.

What was it that brought Jews and Muslims together to make music?

Silver: Jews and Muslims came together to record music, just as their Jewish and Muslim forbears had gathered together to perform music. In itself, this was nothing new. If you go further back in history – focusing on a country like Algeria, for example – you find that the master-disciple relationship was key to musical transmission for many centuries.

Moreover, masters and disciples often alternated between Muslims and Jews. It wasn’t guilded along religious lines, with Jews only teaching other Jews or Muslims only teaching other Muslims. This interweaving was always there in music. What was news to me was the persistence of that intimate relationship well into the twentieth century.

In terms of historiography, the end of the 19th century has always been regarded as the moment of Jewish-Muslim separation. Take France’s promulgation of the Cremieux decree in Algeria in 1870, which legally segregated Jews from Muslims, giving French citizenship to the former while denying that privilege to the latter. Historians have tended to date this moment – in which these two populations went in separate directions under law – as the beginning of the end of the Jewish-Muslim relationship.

What I argue in this book, which becomes quite clear when listening to North African music, is if we “shift our gaze” to this other realm, this certainly wasn’t the case. The Jewish-Muslim relationship remained quite vibrant. Not just musicians, but large Jewish-Muslim audiences were constantly coming together.

Pushing the envelope

How much influence did Western music have on this type of music?

Silver: You can hear multiple overlapping influences on almost any recording of the time, this is in part due to the limits of the technology. Given that the records I write about – 78 rpm or shellac records – could only hold three minutes of music per side, repertoires inevitably had to be truncated. In many cases, the tempo was sped up. You can hear the shift in the Andalusian traditions and all the more so in popular music. On the Andalusian side you also suddenly find instruments that were never there before. The piano and the harmonium are everywhere.

In the popular realm, you hear this not only in the choice of instruments but also in the music itself. For instance, if you listen to an interwar recording from Tunisia, you’ll often find yourself enveloped by cha-cha-cha or tango and jazz. These artists pushed the envelope. It was hugely innovative and that musical innovation clearly captured people’s imagination.

In what way would you describe the recording industry in North Africa during that era?

Silver: The scene was diverse and multi-layered. At the turn of the 20th century, the rise of the recording industry represented something new and unusual. By the interwar period, thousands of individual recordings were moving around North Africa. And individual records were selling thousands of copies. The records with the most appeal – the best-sellers – are those that were subversive, nationalist or anti-colonialist, giving voice to what it meant to be modern in the Maghreb.

An infrastructure for distribution across North Africa also arose at this time. Venues were erected or re-purposed. A star system emerged. There was music happening all over the place. Music was becoming a booming industry.

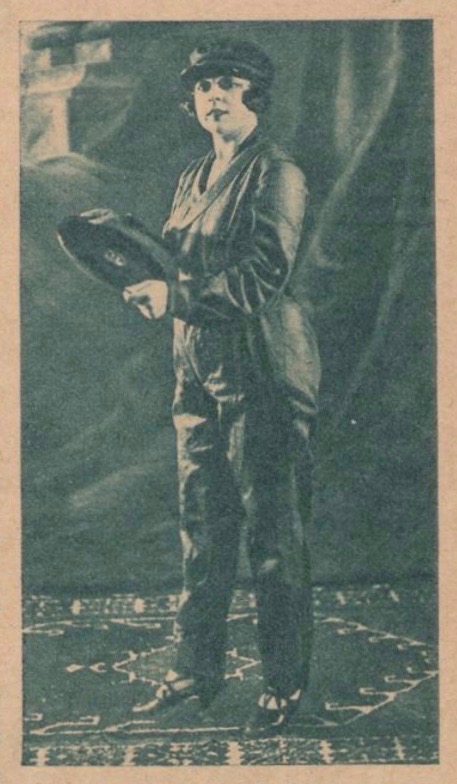

In what way did play gender a role in artists gaining success?

Silver: No doubt, male artists had a much easier time. Part of the reason was that male artists could negotiate contracts in ways that were often not possible for female artists. This meant better recording deals and sometimes even earning royalties. Remarkably, some female artists did manage to secure royalties.

Habiba Messika is a case in point. What she accomplished in the music business would even have been difficult for her male counterparts at the time. She not only negotiated her own royalties, she also recorded for multiple labels at a time of exclusive contracts.

But there were other ways female artists pushed back. We need to concentrate on the risks they were taking. Whether it was in singing material that challenged traditional gender roles, playing the lead with an all-male backing chorus, or performing ribald and risque numbers.

We find women taking centre stage who in many ways were in control of their voices and their business activities. Too often female voices are left out of the narrative. When we move our attention to music, however, women instantly occupy the limelight in really important and influential ways.

What difficulties did you come across while searching for artists, and how much did your archive play a role in writing this book?

Silver: When I first started this project, I was warned that it would be impossible. The idea was that music, by its nature, is ephemeral, fleeting. The problem that lay before me was how to put this history back together.

I found that the traditional archival paper trail ran quite deep, because of the nature of the French colonial regime in North Africa, in which many officials, bureaucrats, and agents were monitoring and paying attention to music for various reasons. There is still much research to be done on this particular aspect.

The compiling of the recordings themselves became its own archive. That any one of these records survived is remarkable. I focused on learning how to read them and discerning the connections between them. Some forms of legibility might be more obvious, like the printed label at the record’s centre, but there are other traces in and around the record. We find inscriptions, for example, noting the moment when someone purchased a record, or someone‘s name on a record so that it could be eventually returned to them in cases of borrowing or loss. Indeed, individuals went to great lengths to preserve the records.

The process of digitising these records and putting them online through Gharamophone.com has meant I was able to engage with the descendants of the musicians themselves. In some ways, I have only begun to scratch the surface of this world. There is so much more work to be done.

Each artist you explore in the book comes with a unique story, which stories did you find most surprising and what are you working on next?

Silver: One element of the story that surprised me was how interconnected this world of recording and music was. Apparently unconnected musicians from across North Africa suddenly appeared in concert together or on the same recording. I was also surprised by the stunning contribution of Edmond Nathan Yafil, who is the focus of the first chapter of the book. Anyone wishing to understand the North African music industry today needs to refer back to a person like him.

I had thought to move away from music for my next book project. But, over the last couple of years, I have come to realise, I can’t and I don’t want to. What I am working on now is in some ways the second half of this story. I‘m taking the moment of decolonisation as a starting point. I‘m following the paths of these musicians and the subsequent generations who fan out to new places around the world. I’m thinking about music and migration, thinking about the endurance of Arab-Jewish identity in the second half of the 20th century, and how it might change how we hear the present.

Interviewed conducted by Tugrul von Mende

© Qantara.de 2022