Is Iraq steering towards post-sectarianism?

While Iraq is in the grip of a breath-taking summer heat-wave, the odour of dissatisfaction rose in the major southern cities of Basra, Najaf and Karbala and swiftly spread to the outskirts of the capital city Baghdad in July 2018. The spontaneous protests began weeks after the general election concluded in Iraq.

On 12 May 2018, Iraqis went to the ballots to elect members of parliament and subsequently a new prime minister. In a sense, these elections were unique in the history of Iraq since the 2003 invasion for three pivotal reasons. Firstly, it was the first general election since the demise of IS and its proclaimed caliphate in Iraq. Secondly, the election occurred a year after a referendum for independence in the Kurdistan region. Thirdly, the election was marred by regional tensions between regional powers.

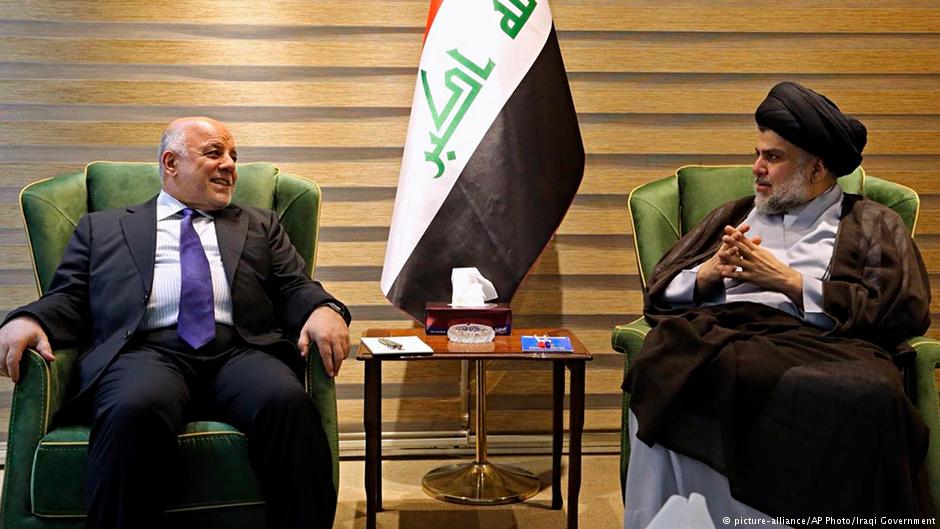

The May turnout was reportedly around 45 percent, the lowest since 2003. In some constituencies, the results of the elections were contested and faced recounts. Nevertheless, many commentators were caught off guard by the results of the ballot boxes. Iraqʹs populist Shia cleric, Muqtada Al-Sadrʹs Al-Sairoon party gained more seats than the incumbent Prime Minister Haider Al-Abadi and the powerful coalition of Iranian backed Shia paramilitary factions of Al-Fateh led by Hadi Al-Ameri.

Al-Sadr led a popular movement advocating a cross-sectarian national government and its umbrella party included non-religious parties, including Iraqʹs Communist Party. Nevertheless, after weeks of behind-the-scenes political haggling over which party will dominate the key ministerial positions, protestors in the south of Iraq poured into the streets.

Demonstrations flared over lack of public services. Residents in Basra went on a rampage after accusing the municipality of financial mismanagement, entrenched corruption and failing to provide basic services and systemic nepotism.

For the downfall of traditional parties

Reportedly in late July, thousands of protesters in Baghdad and the southern cities called for the downfall of traditional political parties. Many Iraqis believe that a generation of certain political elites have assumed a central position in ruling the country since the invasion of Iraq – a system of political patriarchy that has put power in the hands of a few for more than a decade.

One resident of Najaf expressed to me, on condition of anonymity, that for a decade appointed governments had no plans to accommodate the Iraqi nationʹs financial concerns. He added that since the Iraqi government declared victory against IS in December 2017, people have become even more frustrated with the authorities. This is because the Iraqi people witness the political elites keenly turning to their convoluted routine of haggling to obtain more leverage, while paying little attention to the economic concerns of Iraqis.What is important here is that the demonstrations began in Shia populated cities. Since the removal of Saddamʹs regime, the central government in Baghdad has been mainly dominated by Shia parties. That the Shia holy cities of Najaf and Karbala should be the scene of such mass demonstrations is unprecedented.

In fact, recent sporadic unrest had generally been confined to Sunni areas in central Iraq. In 2014, the extremist group IS managed to take advantage of Baghdadʹs failure in accommodating marginalised Sunni communities within the governmental apparatuses, establishing a so-called caliphate that lasted for three years.

In the absence of civil war, the people of Iraq have found an opportunity to demand that the political elite deliver on their election campaign promises. What is important is that the Iraqi protesters chant slogans demanding services and jobs, with an absence of sectarian rhetoric amongst the protestors. It is an accurate reflection of the discontent that has been prevalent during recent demonstrations in southern Iraq. Although the response of the caretaker government of Iraq has been heavy-handed, the protesters continue to focus on their economic demands.

Shia, Sunni and Kurd united in their demands

Another key aspect worthy of mention is that Iraqʹs top Shia cleric Grand Ayatollah Ali al-Sistani, revered by millions of Shias, supported the protests. Sistaniʹs representative stated that "the incumbent government must work hard, urgently, to implement citizensʹ demands to reduce their suffering and misery".

Amid weeks of mass protests, Iraqʹs electricity minister Qassem al-Fahdawin was suspended by the Iraqi prime minister in late July. Subsequently, Prime Minister Al-Abadi began conducting meetings with delegations of local tribal leaders and prominent individuals, promising a range of swift actions to meet peopleʹs economic demands. In late July, Al-Abadi also ordered compensation for poultry farmers who suffered economically due to the bird flu epidemic earlier this year.

On 23 July, the Sunni Arab tribes of Hawija symbolically issued a press statement backing the protests in the southern provinces. In a sense, these demonstrations echoed those that took place in major cities in the Kurdistan region in December 2017. Kurdish protestors in Sulaymaniyah and Halabja took to the streets over lack of basic services and delayed salaries. A resident in Sulaymaniyah expressed to me that many people in Kurdistan have sympathy towards their fellow countrymen in Najaf and Basra, as all suffer from the same pain of lack of basic services and entrenched corruption.

What is clear, however, is that the protests in Iraq are not a revolution. They reflect a new phase of political maturity on the streets of Iraq. The recent demonstrations have brought a new non-sectarian dimension to Iraqʹs socio-political arena. The future Iraq, like the present one, cannot be governed without accountability or with pure impunity. Each pole of power needs to adjust itself to Iraqʹs post-sectarian era.

Like the creak of a sail-rig as a ship begins to turn, a sign of change in Iraqʹs socio-political structure could prove decisive. The time is ripe to turn to a non-sectarian technocratic cabinet that focuses on providing welfare for Iraqi citizens and fighting corruption. But this begs the question as to how the future government will tackle Iraqʹs concerns in concrete terms. The Iraqi people have clearly demonstrated their frustration with the authoritiesʹ inability to address the countryʹs economic concerns in the past.

In a sense, in the new Iraq, the economic concerns and peoplesʹ daily financial struggles transcend tribal and sectarian fault lines. This is a great challenge and also a significant opportunity for policy makers in Iraq to direct the country towards a non-sectarian and non-tribal governance, in which the regeneration of the country forms the main focus.

Seyed Ali Alavi

© Open Democracy 2018