The Voice of Unity

To immerse yourself in the huge body of work by Nusrat Fateh Ali Khan is to engage yourself with the metaphysical. His song seems to depart this world and to carry us beyond our usual perceptions. A French film-maker gave a film about this most important Sufi musician of the twentieth century the admittedly rather bold title, "The Last Prophet".

Nusrat Fateh Ali Khan was born in Lyallpur (now Faisalabad) in 1948, just a year after Pakistan was born in the aftermath of the Indian independence struggle. It would have been hard to imagine back then that Nusrat would turn into one of the most positive figures in Pakistan's history.

The merging of Indian, Persian and Arab cultures

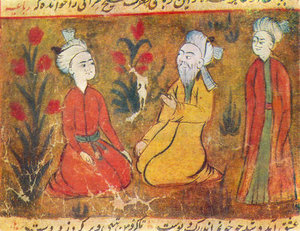

Nusrat's musical style is called Qawwali (from the Arabic word "qaul" – to speak). It's a typical product of the way that Islam developed in South Asia. Qawwali emerged in the 13th century when Indian, Persian and Arab elements joined to create a new musical tradition.

Amir Khusrow (1253–1325), a lyricist and composer at the court of the Sultan of Delhi, is seen as the father of the genre, and his grave in New Delhi is still an important centre of Indian Sufi pilgrimage.

Qawwali quickly increased in importance in an India which, during the Middle Ages, had become a cradle of Persian arts. Many Hindus are said to have been so moved by Khusrow's songs that they converted to Islam. Nowadays, Qawwali is an important part of the daily life of the faithful for over 350 million Muslims in South Asia. There is scarcely a Sufi shrine in India or Pakistan at which songs from the repertoire of Qawwali have not been played, and scarcely a music shop which does not carry Nusrat's albums.

Qawwali hyms are poems set to music, using texts by the classic Sufi mystics such as Rumi and Hafiz, as well as local poets. The texts praise God, the Prophet and the saints, and they express the yearning and the burning love of the one who searches; they carry within them the pain of parting and the joy of unification with the divine.

The aim of experiencing transcendence

Nusrat Fateh Ali Khan sometimes sang in Persian, but he mostly used the Pakistani languages Urdu and Punjabi. In his role as a Qawwal, a lead singer, his task was to breathe life into the verses, to emphasise and lengthen individual lines, and to enrich the basic melody with virtuoso ornamentation. The chorus claps along and repeats what the Qawwal has sung, just as in the Call and Response of Gospel music.

Initially the voice was accompanied just by the Dholak and Tabla drums; then the harmonium, introduced to India by Christian missionaries, was added. The combination of rhythm and text produce an ecstatic state among the listeners: the aim of the song is to let the listeners experience transcendence.

Nusrat's father, himself a respected Qawwal, had other plans for his son: he wanted him to become a doctor, which he saw as a profession which was more promising than the poverty-stricken existence of a musician. But Nusrat, who name means "success", was obsessed with music, and he pushed his father to instruct him in the principles of the art of Qawwali.

Nusrat soon showed himself to be a worthy disciple. He gave his first public performances when he was sixteen years old: when his father died, he sang at the grave at the Chehlum memorial service which is held by Muslims 40 days after a death. His uncle Mubarak then took over his training. Following Mubarak's death, he became the musical head of the family ensemble.

International recognition

Nusrat's fame spread throughout Pakistan and India, but he also soon achieved international recognition: his first tours in the early 1980s took him to Britain and Scandinavia, where he played before a mainly expatriate Pakistani public. Then in the following years he began to sing with Western musicians such as Peter Gabriel and Eddie Vedder of Pearl Jam. He performed at World Music festivals, tried some fusion projects and recorded soundtracks for a Hollywood film. For the first time, Qawwali became known in Europe and the USA.

But Nusrat always remained true to the religious origins of his music. For him, Qawwali was, as in the Sufi tradition, a way to knowledge of God, and thus to self-knowledge, which emerged from the dialogue between the Qawwal and his audience. It was very different from the fast-moving popular music with which he came into contact during his travels.

On the CD "Hommage à Nusrat Fateh Ali Khan", Nusrat is quoted as describing the way in which Qawwali works: "When I begin to sing, I immerse myself in my music, and nothing is left except this immersion. … Thanks to those who went before me, I can deliver the message which they also delivered, and put myself at the service of my listeners, making them susceptible to that message."

There are plenty of recordings on YouTube which document this immersion. They show a large man, surrounded like the Buddha by his disciples, the other musicians. As Nusrat sinks into the depths of his songs, he starts gesturing with his hands in the air, nods and shakes his head in the intoxication of the music. His concerts would often last several hours, sometimes the whole night. His formidable voice was once described by Rolling Stone magazine as the best in the world.

Nusrat died of the effects of diabetes on 16th August, 1997, two days after the 50th anniversary of the establishment of the Pakistani state, but before his own 50th birthday.

For the subcontinent and its two hostile states, Nusrat remains the voice of unity. It's the expression of the common culture shared by India and Pakistan.

For his homeland, Nusrat remains an eternal source of hope which persists even through the most unsettled times. In recent years, there have been terrorist attacks on Pakistan's Sufi shrines; the attacks have been aimed at the heart of Pakistani folk spirituality. Qawwali performance have become less common as a result. But the legacy of Nusrat Fateh Ali Khan cannot be bombed out of existence that easily.

Marian Brehmer

© Qantara.de 2012

Translated from the German by Michael Lawton

Editor: Lewis Gropp/Qantara.de