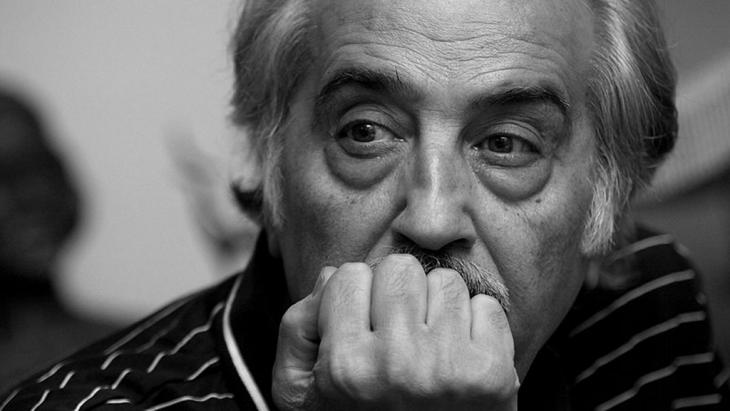

A master of contemporary Iranian letters

Mohammad-Ali Sepanlou was one of the first and foremost representatives of the Iranian writers' association. How important was he for this civil society organisation?

Mahmoud Falaki: Sepanlou really was one of the first people involved in the association's founding and most of its activities. He played a major role both in compiling the organisation's principles and activities also after the events resulting from the revolution. Sepanlou was always a vocal supporter of freedom of speech and press freedom – he was very active on freedom of speech in particular. He had close links to the writers' association up until his death.

Yet we know Sepanlou above all as a poet. I think he wouldn't have been as well known if he had concentrated solely on his other skills: literary criticism, research, translation and even theatre. He's much more a poet than a writer or a translator.

To what extent is it really fitting to call him "the poet of Teheran", and how did that epithet come about?

Falaki: He was given the title after the publication of his three poetry collections, all of which deal with the city of Teheran. One of his best-known poems is "Lady Time". But to be honest, I don't know whether the title is really fitting. In these three poetry collections, especially in "Lady Time", Sepanlou looked at Teheran's history and present day – the city was very close to his heart. In the poems, he tried to let the present and past flow together.

If we call him "the poet of Teheran", people might assume Sepanlou just wrote a standard poem about his native city or about the history of Teheran. But that association would devalue his poems, even make them appear almost worthless. With his poetry collections, Sepanlou not only wrote historical material about Teheran, but also created masterful poetry.

What do you think sets his poetry apart from the rest and what are the characteristics of his poetry?

Falaki: One unique characteristic of his poetry is above all the fact that he – unlike many of his fellow poets – continued his generation's nimai metre. I believe he was one of the last poets to use this metre. And the more he wrote, the better and more fluid his poems became to read. The simplicity of his language was also very characteristic of his style.

In recent years, Sepanlou was frequently confronted with censorship of his work. In some cases, he did not get permission to go to print. In an interview he complained about the situation and said he was considering giving up writing entirely. To what extent did censorship have a lasting influence on Sepanlou's work?

Falaki: Sepanlou was definitely one of the people subject to censorship and one of those who suffered because of it. Some of his works were either not printed at all, or if they were, only in strictly censored form. Sepanlou is certainly not an isolated case; many writers in Iran face censorship. But as far as I know, Sepanlou never really gave up. Some of his works were printed abroad to evade censorship – a method that other Iranian writers resort to as well, incidentally, and one that works quite well. However, there are also a few works that Sepanlou wrote but that haven't been published to this day.

© Qantara.de 2015

Interview conducted by Mitra Khalatbari

Translated from the German by Katy Derbyshire