Old Conflicts within New Borders

A year has passed since Sudan was divided up into two countries. The political conflict between North and South was for decades played out in the form of a bloody civil war, which the 2005 "Comprehensive Peace Agreement" (CPA) sought to end. South Sudan finally opted to secede from Khartoum after a referendum held last year.

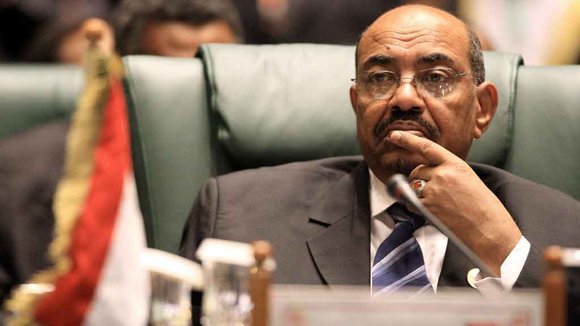

In the run-up to the referendum, not only did Sudanese President Omar al-Bashir offer assurances that he would recognize its outcome, in a gushing gesture he was also the first to congratulate the new country on its new-found independence, and establish diplomatic relations with his new neighbour.

The high expectations linked to the independence of South Sudan went some way to covering up the nation's deep-seated strife – but only for a short period. People living in the south hoped their new status would deliver on long-held dreams of liberation from Khartoum's heteronomy, better living conditions, safer roads, regulated work and also democracy.

The fact that relatively little convincing progress has been made on any of these counts, neither in the South, nor in the North, is just one of many problems that have re-emerged with even greater urgency since last year's secession.

Unsettled disputes

Although months have passed since South Sudan declared independence, the key questions are still primarily concerned with demarcation, the status of southern Sudanese living in the North, the allocation of income from the oil industry, further implementation of the Nile Waters Agreement and regulations governing the use of resources by nomadic tribes on both sides of the border.

"Important goals of the comprehensive peace accord, first and foremost the consolidation of the fragile peace, democratic transformation and the reconciliation of former conflict parties, were not realised," says Jan van Aken, foreign policy spokesman for the Left Party in the German parliament. The fact that these questions were not tackled in advance of the eventual secession and deferred until some point in the distant future is now coming home to roost.

Sudan is still a long way off any kind of effective management of the new border to the South. Disputes over the oil-rich regions of Abyei and Heglig have over the past few months led to several escalations of violence involving not only the armies of both nations, but also armed militias. A CPA protocol envisaged "consultations with the population" for these areas to clarify their affiliation to one of the two states once and for all, but these have not taken place. This places any potential peace talks on a rather flimsy foundation.

Alongside this new conflict arena, other flashpoint issues that may have attracted less attention in the past are again taking centre stage following the secession of South Sudan. Military operations by the Sudanese army in Darfur continue to be the order of the day, and in the Nuba Mountains of South Kordofan a conflict that has been raging for years threatens to take on horrifying dimensions.

In the Blue Nile Province and in the east of the country there have also been vociferous calls for independence in the past. "Although the Bashir government is anxious to make the independence of South Sudan a costly affair, the relief experienced in the South is infectious," says Dr. Alfred Sebit Lokuji, a professor at Juba University. The probability that these demands will grow yet louder is growing, threatening a further division of Sudan.

Apart from that, Sudan is far from being in a position to settle the tribal disputes being played out on its territory. "The longest war, i.e. the war to establish a national identity, has not even begun yet, leaving much room for ethnic conflict to dominate the socio-political scene," says Lokuji.

Extreme inequality between Khartoum and the provinces

The problem affecting the various regions in North Sudan is that there is an extreme inequality between the political centre in Khartoum and rural areas, a disparity reflected by a large prosperity gap.

For decades, the Sudanese government has ruled the country with a policy system dominated by patronage, which swallows vast sums of money from the national budget and in which loyalties and supporters are paid for. In addition, almost 70 percent of the budget is spent on defence. During periods of economic stagnation, such as now without the inclusion of oil revenues, this unilateral application of financing is especially noticeable. Al-Bashir's "National Congress Party" (NCP) has suffered a widespread loss of public faith.

But so far, any demonstrations have remained small in scale. The protest movement in neighbouring Arab states did reach Sudan for a short time in January 2011, but at the moment it is for the most part university students in and around Khartoum who are daring to take to the streets. These protests are few and far between, short-lived and focussed mostly on the daily problems faced by people trying to cope with a poor infrastructure, electricity and water outages and dramatic price hikes.

There are few opportunities for the development of a nationwide protest movement. Apart from the lack of any organisational coherence and the highly repressive approach of security forces, it is the memory of the civil war 20 years ago that dampens any revolutionary spirit.

But there is a chance that the upheaval will be echoed in Sudan in after all. For Lokuji "it is a matter of time! While the Khartoum élite might survive an Arab spring à la Sudan – the way their colleagues in Egypt have survived – fundamental change may not be too far behind."

Van Aken points out that interestingly, both the government and opposition are seeking to foster closer ties with Sudan's neighbours to the north. "President al-Bashir primarily views the Egyptian Muslim Brotherhood as potential allies," he says. "The opposition is keen to associate itself with the progressive movements in Egypt and Tunisia."

Political partisanship for South Sudan?

Internationally speaking, the response to the secession of the South was initially muted. Then the new nation was jubilantly adopted by the international community and congratulated on taking its step into independence. The prevailing official mood was that the Sudanese two-state solution was a positive one.

But apart from the required support for South Sudan, where the government is still struggling to introduce genuine pluralism, democracy and the rule of law, independence provided European countries and the US above all with the opportunity to reset their relationship with Khartoum. There were concrete plans to lift US sanctions against the "rogue state", a pledge that was however revised in view of the latest developments.

Van Aken interprets this approach as "unilateral support of South Sudan". He demands that "future international engagement with both Sudanese states dispense with the good-versus-evil mindset that has been in place up to now" and that diplomatic relations should be re-established with Sudan.

China, on the other hand, is currently attempting a balancing act between North and South. "China's amoral behaviour regarding oil in the years leading to the CPA endears it to Khartoum, but places it in the column of dubious characters where South Sudan is concerned," Lokuji explains. "It is eager to do business with South Sudan for the precise reason it played 'monkey-no-see' while bed-fellows with Khartoum: oil."

For its part, Sudan has been honing its own political profile by heading up the Arab League observer mission to Syria with the figure of General Mohammed al-Dabis. Even if, and perhaps because of the fact that appointing the former head of the country's intelligence service to this post drew criticism – which was then borne out by his comments belittling the situation in Syria – this move is a good example of Sudan's ability to skilfully exploit attention loopholes within the international community. Repressively governed states such as Sudan are only too aware of the fact that western nations' stance on human rights can most definitely be described as diplomatic.

The future of both Sudanese states now depends above all on whether they are ready to make compromises between themselves and work together. On the one hand we have a government that has up to now failed to deliver on the most fundamental tasks involved in nation building, and that at the present time with all probability looks to be heading towards a one-party dictatorship. And on the other hand we have a nation with a stagnant economy where Islamist forces are gaining influence and where the government is desperately trying to crush protests. In view of such a constellation, the political future of the two Sudans remains uncertain.

Annett Hellwig

© Qantara.de 2012

Translated from the German by Nina Coon

Editors: Arian Fariborz, Lewis Gropp/Qantara.de