A Beacon of Civilisation

I have spent my entire life on the borders of the European continent. From the windows of my house or my office, I have looked across the Bosporus and seen Asia on the other side. So when I thought about Europe and modernity, I have always – like the rest of the world – felt a little bit provincial.

Like the many millions of people who live outside the Western world, I had to understand my own identity while viewing Europe from afar. And so, during this process of searching for my identity, I often asked myself what Europe could mean to me and to us all. I share this experience with most of the world's population, but because Istanbul, my city, is situated at the point where Europe begins – or perhaps where it ends – my thoughts and my feelings were always a little more urgent and a little more durable.

I come from one of the many Istanbul upper middle-class families that made the westernising, secularising reforms introduced in the 1920s and 1930s by Kemal Atatürk, the founder of the Turkish Republic, entirely their own.

For us, leading an upper middle-class life in the middle of the 20th century in Istanbul, Europe was more than just somewhere to find a job, somewhere we could trade with or whose investors we tried to attract; it was first and foremost a beacon of civilisation.

Letting our dreams fly more freely

At this point, I would like to emphasise an important point: Turkey has never been colonised by any Western power; it was never oppressed by European imperialism. This later allowed us to let our dreams of European-style westernisation fly more freely without being weighed down by too many negative memories or feelings of guilt.

Eight years ago, I tried to convince those who listened to me how wonderful it would be for all of us if Turkey were to accede to the European Union. In October 2004, relations between Turkey and the EU reached their zenith. Public opinion and a large part of the press in Turkey seemed to be happy that official negotiations between the EU and Turkey were to begin.

Growing chorus of protest

Some Turkish newspapers optimistically speculated that things might develop very quickly and that Turkey could possibly become a full member of the EU by the year 2014. Other newspapers printed fairytales about the privileges that Turkish citizens would get as soon as full membership was secured. Above all, they wrote, investments would be made and unimagined riches would flow into Turkey from the EU's various funds, which would mean that we, like the Greeks, would take a collective step up the social ladder and be able to live as comfortably as other Europeans.

At the same time, the chorus of conservative, nationalist protests against a possible accession of Turkey to the EU grew ever louder, especially in Germany and France. I found myself in the middle of this debate and began asking myself (and others) what Europe really means.

If religion delineates the borders of Europe, I thought, then Europe is a Christian civilisation and in that case, Turkey, whose population is 99 per cent Muslim, while geographically a part of Europe, has no place in the European Union.

But would the Europeans be satisfied with such a narrow definition of their continent? After all, it was not Christianity that made Europe a model for people living in the non-Western world, but a series of social and economic transformations and the ideas that grew out of these transformations down through the years.

To put it simply, the intangible force that made Europe such a magnet for the rest of the world over the course of the past 200 years is modernity. As our trustworthy history books teach us, modernity is the product of such thoroughly European developments as the Renaissance, the Enlightenment, the French Revolution, and the Industrial Revolution. What is decisive here is that the forces behind this paradigm shift were not religious, but secular.

Whenever the issue of the European Union was discussed a few years ago, I said that Turkey should join the EU as long as it respects the principles of liberty, equality, and fraternity. "But does Turkey respect these principles?" was the reply I quite correctly got from people with whom I spoke. And so, the debate started again from the beginning. Today, when I look back on those days, then I cannot help being nostalgic about them and about how passionately we – both in Turkey and in Europe – discussed the values for which Europe should stand.

Today, because Europe is struggling with the euro crisis and the extension of the EU has slowed down, very few of us are making the effort to think and talk about such matters. Sadly, the positive interest in Turkey's possible future membership of the EU has also disappeared.

Part of the reason for this is that the freedom of thought in Turkey is still deplorably underdeveloped. However, the most important reason is undoubtedly the heavy influx of Muslim migrants from North Africa and Asia to Europe which, in the eyes of many Europeans, cast a dark shadow of doubt and fear over the idea that a mainly Muslim country could join the European Union.

It is clear that this fear is leading Europe to erect walls at its borders and turn away from the world to a certain degree. And as the maxim of "Liberté, Egalité, Fraternité" is gradually forgotten, Europe will unfortunately become an increasingly conservative place that is dominated by religious and ethnic identities.

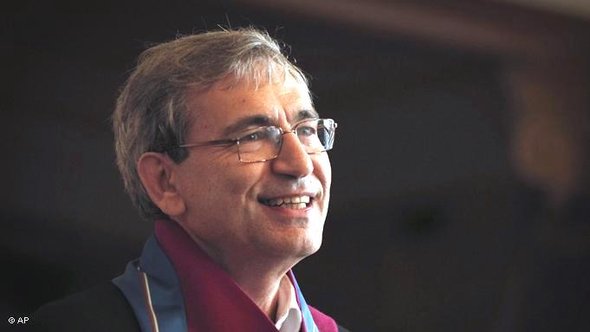

Orhan Pamuk

© Süddeutsche Zeitung / Qantara.de 2012

Orhan Pamuk, who was born in Istanbul in 1952, is a winner of the Nobel Prize for literature. The text printed here is an extract from his acceptance speech on the occasion of winning the Sonning Prize for European culture in Copenhagen.

Translation: Aingeal Flanagan

Qantara.de editor: Lewis Gropp