Teetering on the brink

Yemen has demonstrated remarkable resiliency in the past. To ensure that the recent overthrow of its government by the Shia Houthi rebel movement does not deal Yemen the lethal blow that it has avoided so far, the international community must not abandon the country in what may be its hour of greatest need.

The origins of the Houthi movement date to 1991, when it was created to protect Zaidism, a moderate form of Shiism, from the encroachment of Sunni Islamists. After the attacks on New York and Washington DC on 11 September 2001, the group's battle took on a geopolitical dimension, as its fighters objected to Yemen's decision to collaborate with the United States and enhance bilateral intelligence co-operation.

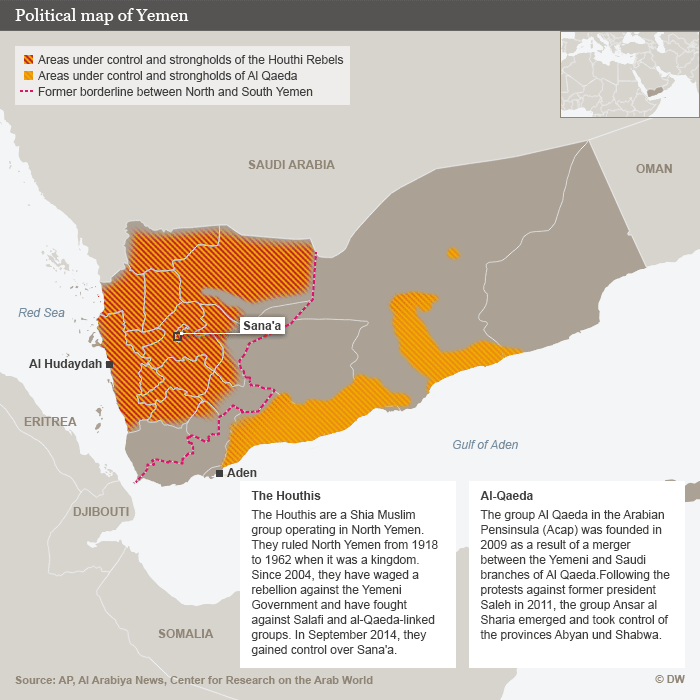

From 2004 to 2010, the group fought six wars against the Yemeni government and even skirmished with Saudi Arabia. Yet it never managed to expand its reach beyond its stronghold in the north of the country. That changed in 2011, when the popular protests and political chaos stemming from the Arab Spring led to widespread institutional paralysis, allowing the Houthis to march past a military that largely refused to fight it.

New alliances with al-Qaida?

The group's power grab has frightened its adversaries, leading them to seek new alliances that could imperil the state's security. In the central region of Marib, home to the oil and gas facilities that Yemen relies on for foreign currency, several tribes have vowed to fight the Houthis. The region was once a stronghold of al-Qaida in the Arabian Peninsula (AQAP), an affiliate of the global terrorist organisation. If the military refuses to assist the tribes – as is likely – they may be tempted to turn to AQAP.

The situation is no less precarious in the southern provinces, where a secession movement has been active since 2007. Southerners are up in arms because the Houthi rebellion halted plans for the adoption of a federal system, which would have given the region greater autonomy. In response, armed groups seized checkpoints and closed the port of Aden. The risk of secession is very real.

Southern Sunnis have been marginalised since a 1994 civil war that left northerners in control of most of the country's political institutions. Many in the region worry that the Houthis will discriminate against them further. AQAP is firmly rooted in this region as well, implying the possibility that local residents will seek its help in defending against an expected Houthi onslaught.

Battleground in a proxy war

Meanwhile, Yemen continues to serve as a battleground in a proxy war between Iran and Saudi Arabia. Iran has armed and trained the Houthis, and, though the rebels' brand of Shiism shares little with that practiced in Tehran, they have praised the Islamic Republic's founder, Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini, and held up Iran's Lebanese proxy, Hezbollah, as a model to be emulated.

When the Houthis took over Sanaa, the capital, in September, Saudi Arabia cut off aid to the country. To make matters worse, falling oil prices and attacks on pipelines imperil a hydrocarbon industry that provides 63% of government revenues. Decreased earnings led Yemen to forecast a $3.2 billion budget deficit last year. If the turmoil is not curtailed and the Saudis do not resume the payments that have long ensured the country's ability to function, Yemen may not be able to cover its expenditures.

The US has followed Saudi Arabia's lead, shuttering its embassy and freezing intelligence co-operation and counterterrorism operations. This is a mistake. Yemen's military is largely intact, having remained in its barracks as the Houthis marched to the capital, and there is little evidence that the units that work with the Americans are loyal to the new rebel government. Suspending co-operation risks giving AQAP free rein in a country where it was able to wreak havoc even when bridled.

Yemen is mired in crises that it cannot solve alone. Unless its international allies throw it a lifeline, it risks being swallowed by a sea of disorder that could imperil the entire region.

Barak Barfi