"I want to write until I die"

Linda Christanty is a small, delicate woman with distinctive, Chinese-looking facial features. Even in a busy café in downtown Jakarta, she commands a noticeable presence.

The eldest daughter of a mining company manager, Christanty grew up on the island of Bangka. Her parents were liberal and Western in their outlook, and cared very deeply about the education of their three children. But like many members of their generation, they were very careful about expressing any political views in the wake of the bloody mass murders of Communists and their alleged sympathisers that followed General Suharto's power grab in 1965.

Christanty's grandfather, however, who was a trade unionist and supporter of the deposed President Sukarno, did not keep his opinions to himself. He passed on his core political beliefs to his granddaughter, for example, that social justice is more important than the accumulation of personal wealth and that one must fight social evils.

The devout Muslim also taught her that it is not important to which faith you adhere, but rather how you express that faith in the way you live your life. In keeping with this belief, the family would give rice and cake to their poorer neighbours on all important public holidays, regardless of whether these neighbours were Muslims, Christians or Buddhists. "I grew up with the awareness that Indonesia is not an Islamic state, but a secular republic," says Christanty, herself a Muslim. She got her Christian-sounding name from her father, who was a great admirer of the tennis player Chris Evert.

Left-wing activism

While studying literature in Jakarta, Christanty met some kindred spirits and joined a left-wing student group in 1992. Following her graduation, she campaigned with the labour movement for better living conditions for factory workers and the underprivileged in the city – a risky undertaking under Suharto's authoritarian military regime.

She eventually went to ground and co-founded the Democratic People's Party (PRD), which was banned in 1996 for its allegedly Communist ideologies. Party leaders were arrested; some were tortured; others never reappeared. During this period, Christanty moved from place to place, hiding in workers' barracks and writing anti-regime material under the pseudonym "Mirna".

When Suharto was eventually forced to stand down in 1998 as a result of the Asia crisis and the overwhelming wave of protest at home, the euphoria soon changed to frustration. The effects of 33 years of indoctrination had left their mark: the civilian population was, politically speaking, completely uneducated and not prepared for the sudden change. The opposition was too fragmented to be in a position to build up a new democracy. And so the power vacuum was filled by the old guard.

In the year 2000, Linda Christanty stopped getting involved in organisations. "I never wanted to be a politician. I wanted to fight for a free country where everyone has the same rights," says the former revolutionary. "My personal goal was always to write. I want to write until I die."

An astute observer

Whenever the 45-year-old surveys the person with whom she is speaking through her square-framed glasses, her gaze flickers with energy and depth. To this day, she is not afraid to speak frankly or to talk about people whose behaviour is anti-social, whether they be corrupt rulers, unethical businesspeople or religious fanatics. But for the dedicated author, who also spends much of her time working as a journalist, it is equally important to always consider both sides of a story: "I prefer to weave my own ideas and emotions into fiction," she says. "In my journalistic work, on the other hand, I try not to make judgements. The facts should speak for themselves."

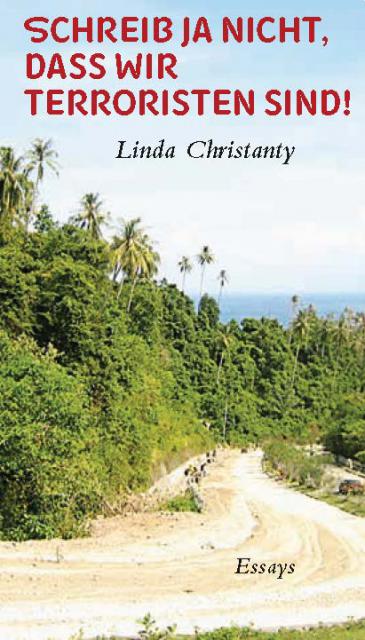

This is the case, for example, in her volume of political essays entitled "Don't write that we're terrorists!", which is soon due to be published in German. In it, Christanty describes her experiences in the crisis-torn province of Aceh, where she managed the editorial offices of the Aceh Feature Service for six years.

She reports on the consequences of the 30-year civil war, which ended only after the devastating tsunami of 2004, a disaster that killed some 170,000 people in Aceh alone. She considers the arduous peace process as well as the introduction of Sharia law in the autonomous province, describes the difficult lives of orphaned children and abused women and tell the personal stories of former rebels or fanatical religious scholars.

The collision of national and international politics

In the final third of her book, she places the events in Aceh in a broader context by focusing on extremist ideologies worldwide, and in South-East Asia in particular.

"The debate about global conflicts influences regions all around the world. In view of the political situation in Syria and Iraq, Islam is often associated with 'terrorism' or 'radicalism'. Moreover, the Palestinians, who are fighting for their independence, are also referred to as 'terrorists'. In certain situations, however, Islam also serves as the collective identity of a community that feels under threat," says the journalist. "For me, Aceh is the best example of how local, national and global politics collide. After the end of the armed conflict, martial law was replaced by Sharia. This has changed nothing in practice: in order to protect their interests, a small group of politicians, businesspeople and clerics continues to suppress critical thought within the civilian population."

The fact that the German translation of Linda Christanty' s book is to be presented at the forthcoming Frankfurt Book Fair is due to the commitment of her good friend Gunnar Stange, an expert on Aceh and research associate at Frankfurt's Goethe University, who published and translated her book.

Although Indonesia is the guest of honour at this year's Book Fair, it is not yet clear whether any of Christanty's literary works will feature there. The selection process adopted by Indonesia's National Committee is not all that transparent.

In any case, her prize-winning short story collections "Maria Pinto's Flying Horse" and "A Dog Died in Bala Murghab" have already been translated into English. Her stories are mostly based on contemporary events that she transposes into a kind of magical realism. The stories also revolve around social and political conflicts, repression and resistance, and also love and forgiveness. "I've inherited my grandfather's ideas. But because I don' t have my own children, I'm passing this legacy on through my books," she says.

Christina Schott

© Qantara.de 2015

Translated from the German by Nina Coon

In 1998 – at a time of democratic upheaval in Indonesia – Linda Christanty received a human rights award for her essay "Militarism and Violence in East Timor". In the years 2004 and 2010, she won the nation's most prestigious literary prize, the Khatulistiwa Literary Award. In 2005, she founded the independent online journalism portal Aceh Feature Service. She has twice been awarded prizes by the Indonesian Ministry of Education.

This article was amended on 14 August 2015.