A mutation of religion

According to the latest estimates from the London-based International Centre for the Study of Radicalisation and Political Violence (ICSR), more than 20,000 foreign combatants were fighting in the civil war zones of Syria and Iraq at the end of 2014. Of these, a good 20 per cent came from Western European countries. Europe is thus the second-most-important recruiting ground for Islamic State (IS) henchmen.

The numbers of those leaving Belgium, Denmark and Sweden to fight for IS are very high. From the small nation of Belgium alone, as many as 440 citizens had set off by the end of last year. This is equivalent to 40 for every one million inhabitants. The figures for Germany are less dramatic. During the period under consideration, 500 to 600 people are estimated to have left the country to travel to the war zones. In comparison to the total population, the ratio is thus seven for every one million inhabitants.

In view of these high numbers, a series of questions present themselves: who is going to war here? What motives do these people have? And what are Muslims and civil society doing to stem the tide of this escalating civil war tourism?

Mostly men in the service of the new "caliphate"

On the basis of the information now available, at least the first question can be answered in a reasonably satisfactory manner. Police and intelligence data as well as reports from schools and youth services show that it is predominantly men who are offering themselves as fighters in the service of the new "caliphate".

In Germany, 89 per cent of the 378 persons who left the country for this purpose up to June 2014 were men. Most of them were between the ages of 16 and 29. The educational backgrounds of the self-proclaimed combatants are heterogeneous. Many have only a low level of schooling, but university students and academics have also chosen to fight in these foreign battles.

For this reason, the British terrorism researcher Max Taylor has pointed out that certainly not all potential jihadists come from socially deprived backgrounds. Some choose to go radical of their own free will. Nor does the religious affiliation of those who leave to fight with IS enable any clear-cut conclusions to be drawn. In addition to Muslims, there are also members of other faiths who have "converted" to this rudimentary form of self-made Islam.

Many Muslim militants were previously not very religious at all and come from families that do not regularly attend the mosque. Also notable is that a significant number of them have a criminal record. Due to this heterogeneity, it is impossible to create a precise profile of the group of those at risk.

Clear statements regarding the factors and processes involved in radicalisation are not possible either. The main problem is the lack of studies that deal with this issue and are based on solid data. Islamic State and its mobilisation strategies are such a recent phenomenon that research results that might be useful for prevention work can be expected to be available in one or two years at the earliest.

The war in Syria as an apocalyptic mission

Notwithstanding the gaps in our knowledge, we can describe somewhat accurately what makes for the appeal of IS. One of the most effective mobilisation factors is the eschatological vision that has been propagated by the highly professional IS propaganda machine for the past two years.

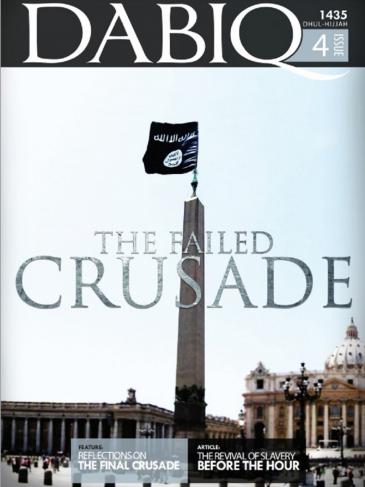

At the heart of this narrative, which is based on a hadith (one of the handed-down teachings, sayings and actions of the Prophet Muhammad), is the small Syrian village of Dabiq, located not far from Aleppo. This is where, it is said, one of the biggest battles between Muslims ("the best people on earth") and the "Crusaders" will take place. The battle will then be followed by the conquest of Constantinople and Rome. In the context of jihad propaganda, the war in Syria thus becomes an apocalyptic mission in which every upstanding Muslim must participate. The mobilisation potential of these apocalyptic fantasies, which are spread via films and magazines on the Internet, can hardly be overestimated.

Mobilisation is further reinforced by other factors inherent to the compact worldview of IS. First among these is a series of psycho-social effects. The crude IS ideology at first allows its devotees the act of self-exaltation. This is made possible by a dichotomous worldview that divides everyone into either "believers" or "non-believers".

Needless to say, the "believers" are ultimately on the right side and thus superior to all those who do not follow IS ideology. This idea is often conjoined with the act of comprehensive self-empowerment. Fighting on a "divine" mission, IS combatants stop at nothing. Even barely conceivable excesses of violence such as mass executions of prisoners of war and atrocities against the civilian population seem permissible in this light. In this way, the war in Syria and Iraq is developing a kind of irresistible attraction for shady characters longing to live out their pathological fantasies of violence.

The term "hypermasculinity" refers to another phenomenon that has hitherto scarcely been examined. Almost all IS propaganda, which is produced by the Al Hayat Media Center, celebrates the good-looking, casually styled fighter type who makes a good impression even in the heat of battle.

Plenty of visuals of this type can be found in the magazine DABIQ, of which seven issues have been published to date, or in the film production "Flames of War". The film shows long slow-motion shots of black-clad young men with beards and shoulder-length hair who effortlessly withstand the shock waves of heavy mortar rounds. Given these images, it is little wonder that IS fighters are celebrated as "lions" and "heroes" in the social networks of the neo-Salafists.

Camaraderie and "good" community

Another significant tool in the recruitment strategy for IS supporters in Europe is the promise of camaraderie and "good" community. The solidarity among IS supporters offers people a sense of equality in a multi-ethnic group. In addition, the community affords its members recognition and respect. No one asks about their former lives or their personal failures. People who join IS can start over, wipe their slates clean.

Finally, it is important to discuss what neo-Salafi mobilisation and Islamic State have to do with Islam and the Muslims. This difficult question has been provoking controversy for quite some time – even among renowned experts.

Some assert that the Koran and Sunna contain passages that can be used to theologically underpin jihadist positions. But this basic assumption is by no means shared by everyone in the fields of Islamic Studies and Islamic theology.

The French scholar of Islam Olivier Roy in particular has repeatedly pointed out in recent years that the neo-Salafi movement is not a consequence of Islamic culture, but rather "the negation of any culture". According to Roy, neo-Salafism is a mutation of religion that makes the sacred texts speak to people outside their actual cultural and historical context by interpreting them literally.

This, he says, makes the staging of religiousness more austere, uncompromising and self-reflexive. Indeed, an analysis of the issues of DABIQ published thus far shows that they contain a simplified, reductionist "theology", one that is clear and unambiguous in contrast to the traditionally complex Islamic teachings. In other words: IS ideology has nothing in common with classic Islamic theology, which speaks rationally about God.

A crude and simple-minded ideology

The same conclusion can be reached on the basis of a statement made by 120 Islamic scholars, which was presented in September 2014. Their words demonstrate in detail that IS violates fundamental Islamic principles.

These findings also cast a new light on the role of Muslim communities in Western Europe. Policymakers and the media have repeatedly called on Muslims to distance themselves from Salafism and jihadism. But what exactly are they supposed to distance themselves from? Salafism and the jihadism associated with it represent a crude and simple-minded ideology that randomly picks up elements of Islam and exploits them for its own ends.

Those bearing the brunt of this exploitation are in every respect the Muslims themselves. Moreover – and this has so far not been sufficiently understood – youth radicalisation processes usually take place outside mosque communities. Many of those involved are converts from Christian faiths or other religions and ideological backgrounds.

As a consequence, the possibilities available to Muslim communities to take preventive action are limited to non-existent. This is why those working in the new field of radicalisation prevention assume that neo-Salafi mobilisation and IS networks can only be combated in the long term through concerted action by all of society.

Michael Kiefer

© Qantara.de 2015

Translated from the German by Jennifer Taylor