Capturing the light of sages

Since the mid-20th century, many in the West have been aware of the masters of the Indian subcontinent. Books such as Swami Yogananda's Autobiography of a Yogi influenced a whole generation in its quest for meaning; so much so that Steve Jobs, for instance, had the book handed out at his funeral.

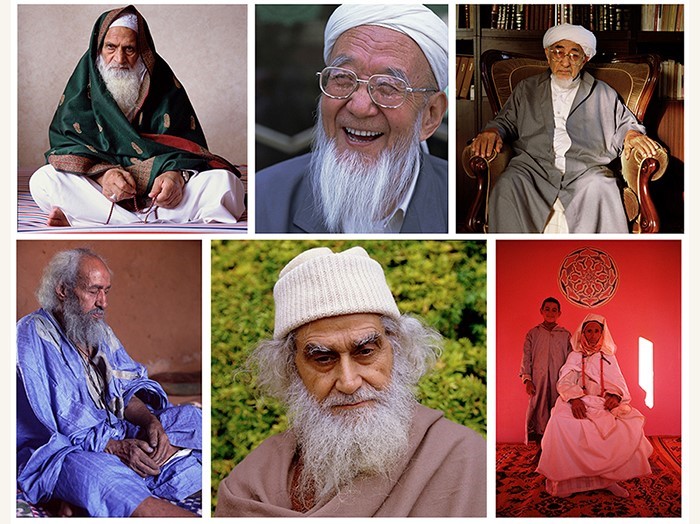

The saints and enlightened beings of Islam, on the other hand, are hardly known to anyone. In mediaeval Islamic mysticism, there is a lively tradition of recording the biographies of great masters in the form of hagiographic legends and narratives. However, the fame of contemporary Muslim saints rarely extends beyond their homelands.

It was thus from a sense of vocation that British photographer Peter Sanders went to seek out saints in the Islamic world and invited them in front of his lens, to be recorded for posterity. For nearly five decades, Sanders travelled between North Africa and Southeast Asia to spend time in the presence of spiritual leaders of Islam and – if they gave permission – to take their portrait.

Yet the early years of Peter Sander's career were very different: in London of the sixties, the young artist made a name for himself by photographing the great idols of contemporary youth culture. Sanders put legends like Bob Dylan, Eric Clapton and the Rolling Stones in front of the camera, taking one of the last photos of Jimi Hendrix before he died from drug and alcohol overdose.

Disillusioned with the materialism in British society

“These people were the poets of our time. They were commenting on what was happening in society,” Sanders says in an interview on Zoom, sitting in his study in front of a shelf of photo books and records. "Before I embarked on a spiritual journey, those were my reference points. However, after becoming a Muslim, my reference points came to be men of wisdom." In retrospect, he sees rock stars as similar to the poets of the jahiliyya – the period of ignorance in Arabia before the Prophet Muhammad – because they were poor role models to base a life on.

Disillusioned with the materialism and hedonism in English society, Sanders, like many of his contemporaries, embarked on a spiritual quest to India. In 1971, following a dream, he embraced Islam as a spiritual path. Three weeks later, he travelled to Morocco and had an encounter that was to have a profound impact on his life – a meeting with Muhammad ibn al-Habib, Sufi master of the Dharqawi order.

The encounter with al-Habib in Ramadan 1971 is documented at the beginning of Meetings with Mountains, Sanders’ impressive volume of photographs. Besides the impactful shot showing the saint in white robe and turban, with kohl-rimmed eyes and prayer beads, Sanders describes how his initial shyness dissolved in the saint’s presence:

"It felt like we had slipped into a still pool of peace, and under his gaze my fears suddenly and inexplicably melted into ease. There was very little conversation. Sayyiduna Shaikh emanated a compassion that filled the room. When he did speak to me, it was with great gentleness and an acceptance of all I was, without any judgement."

Not charisma, but a quality of the soul

It was then that Sanders got a sense of what is called in Sufism an insan-i kamil or "perfect man" – a person who has realised the highest potential in himself: "There is something special about looking into the faces of these people. They have beautiful faces. It is not about charisma, much more about a quality that comes deeply from the soul. It is so refined that you can easily miss it."

In addition to Morocco and the Maghreb, Sanders documents spiritual leaders from Egypt, the Arabian Peninsula, Turkey, Syria, the Indian subcontinent, Central Asia and China. The portraits are touching. There is nothing of folklore about them, but they convey a sense of the deeply transformative potential of Islamic spirituality.

"Taking portraits was never easy for me, because I am rather shy by nature. I had to first find the courage. But it is easier with those people, because they don’t have any ego. It’s harder with people who have an ego, as they put on a mask," says Peter Sanders. "Many of these saints have never been photographed before. That's because of their modesty, because they don't want to give the impression that they are something."

Over the years, Sanders noticed that many of his subjects died just weeks after he had photographed them. Muhammad ibn Al-Habib also died in early 1972 while on the way to Mecca on his third hajj. What at first seemed to Sanders like an uncanny chain of coincidences soon led him to realise that the old masters' willingness to be photographed might actually stem from their knowledge that they would soon leave the earth.

In fact, Sander's photographs are often the only pictures ever taken of the respective saint. They thus carry a historical significance of which Sanders only became aware in retrospect. "It's important that we get to see the faces of these people. It is as if this picture has been removed. We need to restore that image of Islam," says Sanders. "Many Muslims today don't even know why they are actually Muslims. Many feel alienated from the religion as it is lived at the moment. We live in such divisive times. Especially now it is important to bring people together."

© Qantara.de 2022