What can an Islamic scholar tell us?

Some time ago, a group of devout Muslims announced that they intended to give every German a generally-intelligible edition of the Koran. To invite their fellow citizens to read the Koran, these devout Muslims planned to stand about in pedestrian precincts and go around ringing people′s doorbells. At the same time, they also intended to run a poster campaign bearing the slogan: ′Read!′ – Read!

In the generally-intelligible translation that was to be distributed in the pedestrian precincts, this constituted both the opening of Sura 96 and also, according to these devout believers, the very first word God said to the Prophet: iqra` bismi rabbika lladhi chalaq / chalaqa l-insana min 'alaq – Read! in the name of your Lord, who created / Created man from a clot of blood′.

Their announcement caused quite a stir and indeed disquiet, among the German public. The devout Muslims were the top story on the television news; they found themselves on the front pages of national newspapers and were invited onto talk shows on the main public TV channels. The German Interior Minister also expressed his concern and the security services declared that they were keeping a very close eye on these people.

The devout Muslims themselves firmly rejected any suggestions that they had extremist sympathies, pointing out that the Bible was also given away for free in generally-intelligible translations. Their campaign should not, they said, be seen as a mission – there is no such term in Islam – but simply as dacwa, an invitation. Why shouldn′t one read the Koran just as one reads the Bible?

Yes – why not?

Like so many debates that are whipped up into minor hysteria by the constant noise from all sides that constitutes the shaping of public opinion nowadays, the one about handing out Korans also died down quickly. The devout Muslims didn′t have enough money to print eighty million or fifty million or even one million copies of their Koran, nor were there enough volunteers all over the country to invite people to read it.

It eventually emerged that the Koran had only been distributed in those pedestrian precincts that were also furnished with television cameras. And yet the question remained, hanging in the air and in the press, as well: why shouldn′t one read the Koran just as one reads the Bible? The newspapers and talkshows, the interior minister and the security services all provided answers.

But philology can give answers that are more exciting, more logical, even more politically relevant – that is, exemplary philology like that of Angelika Neuwirth. If one wished to reduce her research to a single denominator, a single statement, a fundamental theme, it would be this: the Koran itself is the reason why it shouldn′t be read like a Bible.

It begins with the dating of Sura 96, which, if one examines it closely, can hardly be the first, and it continues with the simple Arabic wording that the devout Muslims obviously failed to understand. In Koranic Arabic, iqra` means not ′Read!′ but ′Declaim!′, ′Recite!′ or even ′Repeat!′ The Koran itself explicitly denies that the Prophet was presented with a written document, comparable to Moses′ Decalogue.

The modus of revelation is repeatedly given as the spoken word: spoken aloud, recited like a cantilena, or even sung – rattili l-Qur`ana tartila, as it says elsewhere in the Koran. The poet Friedrich Ruckert translated this section into German more beautifully and more precisely than any devout Muslim: ′Singe den Koran sangweise,′ he wrote. ′Sing the Koran like a song.′

The Koran is not a Bible

The Koran is not a Bible. As obvious, even banal, as this statement sounds, its implications have been flagrantly ignored – not only by the general public, but also, for many years, by Orientalists, who based their assumptions on Christian theology and Old Testament scholarship in particular.

It is thanks in no small measure to Angelika Neuwirth′s early research that, since the 1980s, the realisation has gained general acceptance, in Western scholarship at least, that the Koran is neither a sermon about God, nor spiritual poetry, nor a prophetic speech in the Ancient Hebraic style. The Prophet certainly did not compose his revelation as a book, to be read and studied alone and in silence.

The Koran′s own conception of itself is as the liturgical recitation of the direct speech of God. It is a text intended to be read out loud. The written word is secondary and until well into the twentieth century it was, for Muslims, little more than an aide-memoire. God speaks when the Koran is recited: in the strictest sense, one cannot read it, one can only hear it.

In this context, Angelika Neuwirth speaks of the sacramental character of Koranic recitation. Although Islam does not use this term, it is essentially a sacramental act to take God′s word into one′s mouth, to receive it through the ears, to learn it by heart: the sacred is not simply remembered, the faithful physically take it into their bodies, actually absorb it, much as Christians do Jesus Christ when they take Communion. (This, incidentally, is why singers are supposed to clean their teeth before declaiming the Koran.)

And now devout Muslims appear on German television and announce that they will be handing out unsolicited Korans in pedestrian precincts and on people′s doorsteps. You only have to have read a book, or a single article, about the Koran by the non-Muslim scholar Angelika Neuwirth to comprehend the presumptuousness of these devout Muslims, who are disregarding the linguistic structure of the text and the history of its reception; to appreciate the sacrilege that, in their zeal, they are committing.

You need only think of the fact that in Muslim households the Koran is, to this day, kept in the place of honour, wrapped in precious cloth. The whole Islamic tradition holds that merely reading aloud from, listening to or touching the Koran – by Muslims themselves and certainly by those of other faiths – requires them to be, if not actually ritually purified, at least in a state of respect, humility and contemplation.

Because in reciting or hearing the Koran a Muslim relives nothing less than the initial act of revelation: it is not a human voice, it is God himself speaking to him or her. This was why, in former times, Muslim military leaders would avoid taking manuscripts of the Koran into battle so that the word of God would not fall into the hands of unbelievers, and why those of other faiths were sometimes even forbidden to learn Arabic on the grounds that they would then be able to recite the Koran.

These are curious, perhaps even extreme examples, yet they are indicative of the scruples that Muslims have always retained with regard to the Koran. And now these devout Muslims wanted to distribute the Koran like a leaflet, or a product sample, with no reservations about copies of the Koran ending up, like all leaflets or product samples, in the nearest rubbish bin.

Treating the Koran unscrupulously

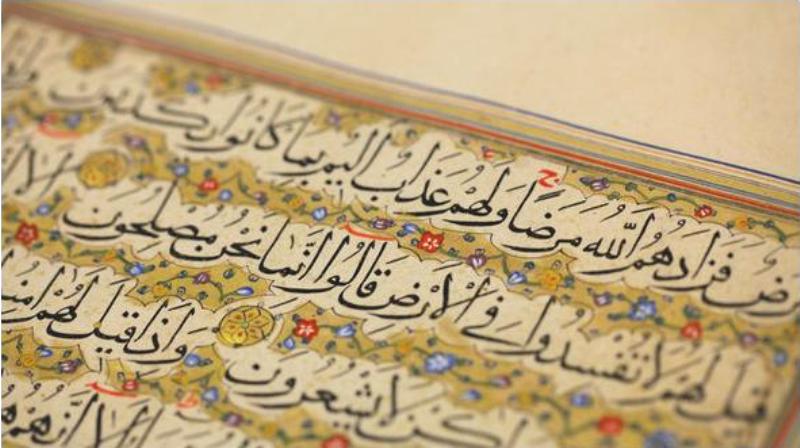

And what an edition, what a devout yet insipid German edition of the Koran, all too easily intelligible and therein falsifying the heart of the Koran, it was that the devout Muslims wanted to distribute! Even the opening of Sura 96 that they quoted on the posters, the supposed call for the Prophet to read: this, in Arabic, is a rhyme – iqra` bismi rabbika lladhi chalaq / chalaqa l-insana min calaq.

It is a rhyme, as all the verses of the Koran, without exception, rhyme. The Koran is legato, rhythmic, onomatopoeic language. You cannot simply read it as you would read a story or the wording of a law. Anyone who opens it without preparation is initially confused.

To him (or her) the Koran appears disjointed; the reader is bothered by all the repetition, the mysterious or incomplete sentences, the allusions whose references remain enigmatic, the drastic changes of subject, the lack of clarity with regard to the grammatical person, the ambiguous imagery.

The difficulty of reading and comprehending long passages from the Koran is not one that arises only in pedestrian precincts. Right up to the present day, Western academics, especially those influenced by their study of the Bible, have disputed the authenticity of the Koran on the basis of its chaotic, indeed arbitrary-seeming structure.

They claim that the Koran in the form in which we know it today is the product of a later age and owes its existence to many different authors whose writings were assembled at random. Muslims, of course, deny this, as a later date of origin and authorship by an anonymous collective would render the entire foundation of Islam obsolete.

All devout Muslims should read Angelika Neuwirth. She made her reputation as an academic with her first great work, the ″Studies on the Composition of the Meccan Suras″, in which she demonstrated the poetical homogeneity, the internally consistent image matrix and extensive textual integrity of the Koran through a microscopically precise reading of the text.

Exactly those things that appear enigmatic, disconnected, tiring to the ordinary reader and especially to the reader of a generally-intelligible translation – the repetitions, anacolutha, ellipses, insertions, the sudden changes of the grammatical person or the apparently surreal metaphors – are what characterise the quality of Koranic language for an Arab listener and explain why James Joyce was fascinated by the Koran.

Thus, historical-critical textual analysis, which devout Muslims often claim is directed against Islam, broadly confirms the traditional picture of Islamic salvation-history. The Koran is, in its essential components, the work of a single period and of an ingenious, linguistically highly-gifted intelligence. The question is: who was this intelligence?

The answer Angelika Neuwirth provides to this question is, for the devout, a far more uncomfortable one. In the work she did after the ″Studies on the Composition of the Meccan Suras″, she turned her attention to the oral character of the Koran and demonstrated its performative elements. What is meant by this is that the Koran is not simply a text that must be read aloud and which, like a musical score, is only realised in performance.

No – the text itself, as it stands, is in part the written record, the carefully-edited transcript, of a public recitation, a performance, written down after the fact. The Koran thus does not consist solely of the statements of a single speaker: it incorporates interjections from an audience of believers, or of unbelievers – as well as spontaneous responses to these interjections, which repeatedly lead to abrupt changes of subject.

God speaks, Man answers

This, however, means that the congregation, those who were the first to hear the Prophet, made a substantial contribution to the Koranic text and the transition from an oral to a written culture takes place in the Koran itself.

If we read the Koran as precisely as Angelika Neuwirth demonstrates, it becomes clear that the Koran is not dictation, but a conversation: for and against, question and answer, puzzle and solution, warning and fear, promise and hope, the voice of the individual and the refrain of a chorus. That God speaks in the Koran is something one has to believe. But philology is enough for us to see that, in the Koran, Man answers.

This conversation that is the Koran takes place not only with the Prophet′s immediate listeners on the Arabian peninsula in the seventh century. In her more recent work, culminating in the propaedeutics of her Koran commentary, which runs to several volumes, Angelika Neuwirth reveals that the Islamic revelation is embedded in the culture of Late Antiquity – i.e. the same period and cultural realm in which Jewish and Christian theology also developed.

This is not, however, one of the usual lists of ways in which Arab thinking influenced Western scholarship. The fact that one of the main strands of the European Enlightenment can be traced back to Arab culture and to Judeo-Islamic philosophy in particular, is something that has been known in Germany at least since the period of Jewish scholarship – even if Germany′s current Minister of the Interior is still unaware of it.

Angelika Neuwirth is concerned with something else. She makes clear that the Koran itself, the founding document of Islam, is a European text – or vice versa: that Europe, according to its origins, also belongs to Islam. The explosive contained in this research is something no security service is capable of defusing. It will rock the foundations of our intellectual landscape for a very long time to come.

Angelika Neuwirth′s most recent work, the first volume of her Koran commentary, gives us an indication of just how enriching this shock might be. By tracing the various Biblical, Platonic, patristic and Talmudic references in addition to the ancient Arabic and inner-Koranic ones and above all by paying serious attention to the linguistic structure of the Koran as a poetic text, a musical score for sung recitation, the extent to which the Koran has breathed in the entire culture of the eastern Mediterranean becomes apparent. And the extent to which, in turn, its exhalation has permeated this, our culture.

In my laudatory speech I have referred only to Angelika Neuwirth′s tremendous and excellent work on the Koran. Acknowledging her numerous essays on classical and modern Arabic poetry, such as those on the important Palestinian poet Mahmoud Darwish, would require a whole other speech.

I have also omitted to depict Angelika Neuwirth as an instigator, which she is as well: the instigator not only of the Berlin-Brandenburg Academy of Sciences′ comprehensive project on the textual history of the Koran, but also of countless smaller research projects.

Almost everyone in Germany who is engaged in working on the Koran or classical Arabic poetry – including myself – has been taught by her, infected by her enthusiasm and supported by her loyalty. At the same time, she also spends many months of the year in the Middle East, keeping a room in Beirut and another in Jerusalem, supervises a whole host of religious students from the Muslim world and gives lectures not only at Harvard and Princeton but also at many Arab universities, as well as at the most important Islamic institutions.

Taking the Other seriously

For as long as I have known her I have been asking myself how she manages it. Time is one aspect – so much work crammed into just one life! But why is it that people, even those at the heart of Islamic scholarship, listen to her so closely, even though her research may touch, even undermine, the very foundations of the Muslim faith?

I believe this has to do with her attitude, her empathetic fidelity to the text, her seriousness and with her own piety. And perhaps this is something we can learn from this philologist in terms of the way the secular public realm relates to religion.

We may question that which is sacred to others; we may, of course, criticise the fundamental principles of any religion. But we should respect the fact that, for others, these fundamental principles are sacred and we should take this seriously. I would like to congratulate Angelika Neuwirth on being awarded this year′s Sigmund Freud Prize.

Navid Kermani

© Goethe-Institut / Fikrun wa Fann 2014

Translated from the German by Charlotte Collins