Midwife of the Middle East

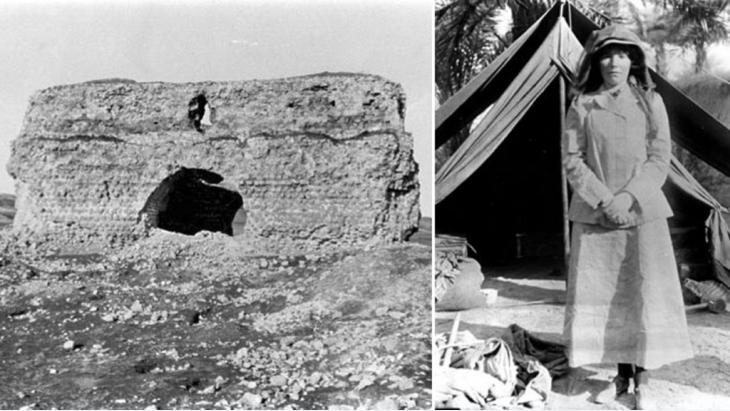

They buried her in Baghdad. This is the short sentence ending the biography of one of the most important women in recent Middle Eastern history. Gertrude Bell, "Queen of the Desert", as the film by Werner Herzog called her. Or "Mother of Iraq", as the inhabitants of the region between the Euphrates and the Tigris describe the woman who brought them both a blessing and a curse.

The search for her grave in the Iraqi capital is something akin to a small-scale odyssey. "No, she's not here," claims the cemetery guard at the British memorial cemetery in the heart of Baghdad in Bab al-Muadam and takes the visitor along the rows of graves. Here lie soldiers of his majesty, King George V. of Great Britain. Most fell in 1917.

A small mausoleum has been erected on the extensive site for Sir Frederick Stanley Maude. The General made a name for himself in the campaign on the Mesopotamian front during the First World War, as conqueror of Baghdad. Following the invasion of Iraq by British and American troops in 2003, the British named their headquarters in Baghdad's Green Zone "Maude House".

A new Middle Eastern order

"Go and have a look at the Armenian cemetery, if you want to find Miss Bell," the guard at the British cemetery finally advises. But she's not there either. When the woman that created Iraq died, on 12 July 1926 in her adoptive city of Baghdad in circumstances still unexplained to this day, she had already lost considerable influence.

A secret agreement between the governments of Britain and France had already decided on the allocation of the Ottoman spoils of war. But it would be another two years before the final demise of the Turkish Empire. Nevertheless, the new Middle Eastern order was a done deal and would from that moment bear the signature of Gertrude Bell.

Initially an unofficial employee of the British secret service, and later as a political liaison officer ranked as a major and 'oriental secretary', she played a decisive role in the foundation of modern Iraq and was a close confidante of the Iraqi King Faisal I, who initially became King of Syria. When the French hounded him out, the British installed him in Baghdad on Bell's insistence.

Thereafter, the Hashemite King no longer needed Bell and the English also distanced themselves from a woman who was highly unusual for her time. This explains why she did not find her final resting place at the British memorial cemetery.

There was intense animosity between Gertrude Bell and Mark Sykes, one of the two leaders in the negotiations to reach the secret agreement. He called her a "flat-chested, man-woman, globe-trotting, rump-wagging, blathering ass." She, meanwhile, accused him of huge incompetence.

This is because the agreement forged by Sykes together with his French counterpart Francois Georges-Picot was controversial at the time of its signing. Picot was the far more experienced partner in the negotiations and knew how to secure much more for France than expected. The agreement also contained serious contradictions. Whereas previously, Britain had pledged it would support the Arabs in the event of a revolt against the Ottoman Empire, and the prospect of recognising a subsequent Arab independence had been set out, France and Britain were now dividing up huge areas of the Arab territory between them and creating nations like Syria and Iraq.

The Sykes-Picot agreement did however also contain, in the first paragraph, a reference that both France and Britain were willing to recognise and protect an independent Arab nation in the regions of the map marked with A and B. But within their spheres of influence, both countries retained privileges that would remain in place until the 1950s.

Modern Iraq′s birth defect

Gertrude Bell, who although employed in the service of the British, always lobbied for the interests of the Arabs, did not agree. Mark Sykes did not care. He was more interested in the fate of the Armenians, who had suffered under the pressure of the Ottoman Empire, than for the retention of the Arabs and the Kurds and threw his weight behind the emerging ambitions of the Jews for a territory in Palestine.

The development shows how bloody conflicts grew from these differing interests, and how these conflicts are now being exacerbated. The forcing together of the three ethnically and religiously diverse provinces of Mosul, Baghdad and Basra brought misfortune to Iraq. The kingdom was always unstable, and was toppled in a military putsch in 1958. The socialist Ba'ath Party seized power in 1968, and Saddam Hussein established his dictatorship in 1979. He held the nation together with what can only be described as archaic brutality.

Ali Mansour opens the sheet metal door to the small Anglican cemetery in the "Bab el-Sher Shi" neighbourhood on the eastern banks of the Tigris. The 72-year-old Shia has been looking after the few graves here for almost 50 years.

In the midst of mosques, churches, ministerial buildings, pot-holed streets and endless queues of cars, stands a stone sarcophagus with the inscription: Gertrude Margaret Lowthian Bell. A small bouquet of red and white plastic roses has been placed upon it.

Asked about the significance of the dead woman to his country, Mansour says diplomatically: "There are good and bad sides to everyone." The same applied to Miss Bell. On the one hand she was responsible for the unfortunate border demarcation and the entity that is Iraq, which did not exist previously. But on the other, she was a perpetual champion of the cultural heritage of the nation and founded the Iraqi national museum. "She spoke our language, knew our clans, our customs and traditions," says Mansour.

What she didn't know, were the differences between Sunnis, Shias, Arabs and Kurds. "If she had, much of this could have been avoided."

Birgit Svensson

© Qantara.de 2016

Translated from the German by Nina Coon