Who ate the sky?

On a public square in Damascus, a man searches for his lost identity card. Bent forward, he scans the ground. Soon the bending turns to crawling and then to prostate desperation. The ID, which just minutes earlier had been in his trouser pocket, has gone. It doesn't take a lot of imagination on the part of the reader to recognise in the loss of the document a metaphor for the plunge into identity crisis.

The scene forms part of a nightmare that writer and poet Ra′id Wahsh describes in the first person in a monologue about his life in "Khan ash-Shih", a sprawling settlement, once a Palestinian refugee camp, on the southern perimeter of Damascus. Thirty-five-year-old Wahsh's story is one of a life defined by war.

The loss of identity in the square is reflected in a higher sphere by narrator Wahsh, a reflection that literally shakes the foundations of existence when the witness to the horrors of war tells us that a substantial piece of the blue sky above Damascus is missing, "as though torn out by the enormous teeth of some terrible monster."

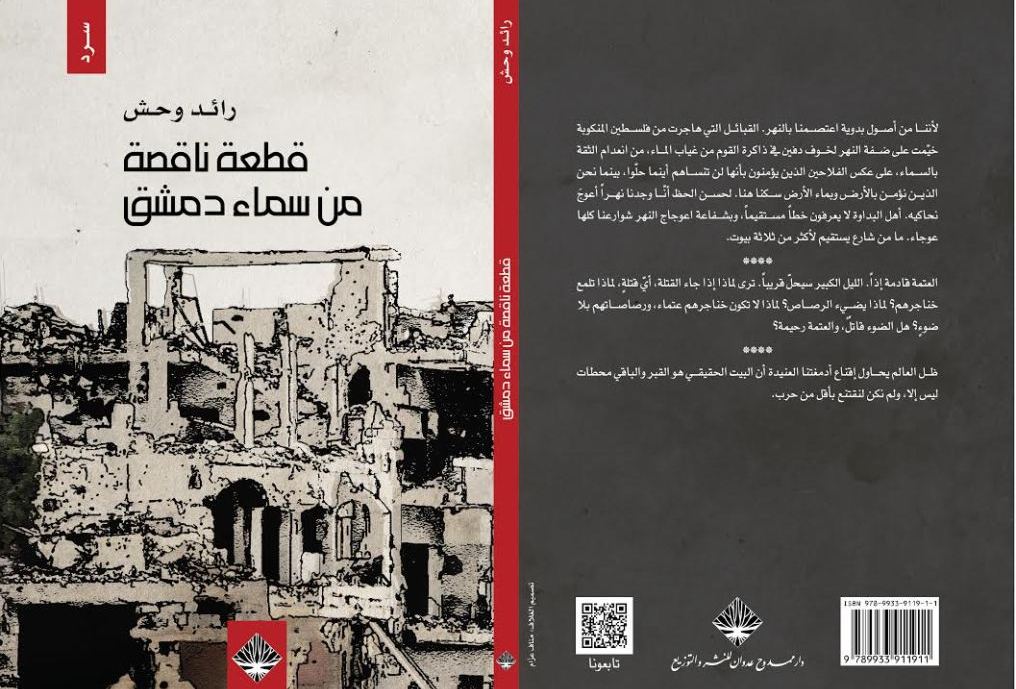

"A missing piece of Damascus sky" is Wahsh's self-communication from the Syrian war. Close observation of reality is central to the work, though, over and over again, the author reshapes real events into fantastical allegories. From this unusual merging of reality and fiction, the reader senses an unarticulated yet incredulous question beginning to emerge: "Can this really be happening?" So far, there is no translation of the Arabic original, though this slim volume definitely deserves to be better known.

Back to the bestial

Though unable to find his ID as he crawls over the Damascus square, the first-person narrator does succeed in leading the reader to a shocking question. Are we still human? The question Syria now faces is about more than whether people can still feel themselves part of a state that bombs its own cities and is thus engaged in its own disintegration. In Wahsh's work we see evolution itself in reverse. Amid the shattered ruins and the roadblocks, people slide down the evolutionary ladder, reverting to animals. The regime militia "bark" at checkpoints and during house searches. Even the narrator "howls like a wolf" against the cacophony of artillery fire at dawn. He finds some hope in a piece of cheap "La Vache qui rit" cheese. As he wolfs it down, he fantasises about being "transformed into a herd of laughing cows".

When human communication is reduced to spreading hate, language itself begins to disintegrate. What remains are animal noises and animal gestures.

Wahsh is clearly opposed to the Syrian regime, which he describes as "neo-fascist". Above the entrance to a military barracks for the training of new recruits, a sign bears the inscription "Man Factory". In spite of barrel bombs and torture chambers, however, the author does not take sides with the armed rebels. These are people, after all, who are responsible for closing down the last bar in the district where aniseed brandy (arak) was still available. When a fighter informs him that "victory" is imminent on a certain sector of the front, Wahsh knows very well that there can be no victors in such a war.

Wahsh, who has also published four volumes of poetry, becomes a chronicler of social regression in this prose monologue. Son of a Palestinian Bedouin family that fled from the shores of the Sea of Galilee to a refugee camp on the outskirts of Damascus in 1948, he draws his material from collective traditional memory.

The poverty he experiences during the bombing reminds him of how his grandparents had lived in Khan ash-Shih. Just as they had done almost 70 years ago, he, too, lights an oil lamp against the darkness. Electricity proves to be a temporary acquisition. In this story, the "darkness" is "no metaphor", however, it is its "essence". His two younger sisters left the camp today to look for food, "barefoot", just as his grandmother had done when she had arrived in the camp decades earlier.

Wahsh provides a glimpse of what everyday life in a war zone is like, from the inside. It is not a static picture however, but one that tells us how conditions change over the years. In the early days, for example, people were still panicked by the thought that the intelligence services might be watching their every step and listening to their phone calls. In the meantime, indifference has become the norm. Worries about surveillance are not a priority when the reality of war has become so familiar.

″War against nature″

Particularly detailed and striking are Wahsh's descriptions of how the people are now waging a "war against nature", rather than each other. In winter, they had begun ″a collective attack with axes and saws″ on olive, apricot and cypress trees. The wood from the trees was to be used for heating. Entire groves wiped out within only a few years. The suggestion implicit here is that the war in Syria is about more than just deciding which side in this brutal conflict is the strongest. This is a society that is also destroying its vital natural resources, the foundations of life itself.

Not everything in Syria was good before the war, on the contrary. But now, even the morbid normality of the recent past has suddenly become elevated to something fondly looked back on and idealised. Though critical of religion, the narrator, who had always been critical of the "disturbance to his night's sleep" caused by the early call to prayer, now regrets that the prayer caller has fallen silent. The ansence of the "Adhan" is a sign that the front has come too close.

In one nightmarish vision, the corpse of a man rises from the ruins of a bombed house. This reanimated corpse, a friend of the author, looks down at the blood running from his wounds and shakes the dust from his tousled hair. "It's what you deserve," it cries out to the other bodies buried beneath the ruins. At such points the monologue takes on a profound ambiguity. On the one hand, "It's what you deserve" reflects the cynical attitude of the regime to the victims of its air raids. On the other, the corpse's interjection also raises the question of collective responsibility for the catastrophe in Syria. What could each individual have done to prevent this situation from arising in the first place?

″Zero hour″

"A missing piece of Damascus sky" is Syrian Trummerliteratur (rubble literature). As such, it is likely to strike a chord with German readers. It is a literature suffused with a sense of things falling apart, the destruction of a way of life and of a society – "zero hour".

"Are we still here? Is this still the old earth? Have we acquired no hide, eh? Have we grown no tail, no beast's jaws, no talons? Do we still walk on two legs?," asks returning war veteran Beckmann in Wolfgang Borchert's drama "Draussen vor der Tur" (The Man Outside, 1947).

A German reader is unlikely to miss the similarity between the Syrian Arabic text and German short stories of writers such as Boll and Borchert. Like the writers of Trummerliteratur, Ra´id Wahsh is aware that after so many years of propaganda, the language needs to be reinvented if it is to be able – once again – to express true understanding and emotions.

"I have collected information from brothers, friends and residents of the camp. Enough material to have written a novel," says the narrator towards the end of his self-communication. But who could have the strength to write a novel where reality so overpowers imagination?

When the Syrian war comes to an end, if it ever does, Wahsh is likely to witness it from Germany. He fled here with his family after being smuggled out of Syria with the paid assistance of traffickers, including both regime soldiers and rebels. There is no missing the irony in this final metaphor: when it comes to the paid removal of the voice of reason from the country, the regime and its oponents are on the same side.

Stefan Buchen

© Qantara.de 2017

Stefan Buchen is a television journalist who works for Germany's ARD "Panorama" programme.