"Head Straight on to Europe!"

"Do you have a pound for a berth on a boat to Italy?" asks an old one-eyed man with a walking stick, turban and long bushy beard. He's grinning through the open car window. In the run-down Egyptian coastal town of Abukir, west of the Mediterranean port of Alexandria, even the beggars have a clear aim – and that lies behind the sea's horizon. The hope is there, where the Europeans sunbathe on the beaches, or it dies on en route.

If Abukir was once the place where Britain's Lord Nelson and his Royal Navy sank Napoleon's fleet, today it is the place where refugees, most of them Syrian, embark on the dangerous crossing to Europe. Syrians are paying up to 4,000 dollars for a berth on one of the boats, says Abou, who runs a small kiosk on the beach. The boats mostly set sail at night, full to capacity with around 200 people on board and a few smaller boats in tow.

The refugees are transferred to the smaller craft shortly before reaching the Italian coast, and then it's just a matter of heading straight on to Europe! "For those who drown, it's tough luck, those who get there, well, they've made it, and those who are arrested, that's just the way it turns out. The traffickers win whatever happens," Abou summarises the people smugglers' business model.

The boats are only worth a fraction of what the Syrians crammed onto them have paid. Sometimes the refugees are set down on one of the few small off-shore Egyptian islands, where they are later picked up by the coastguard and arrested.

Firing on refugees

One such boat set sail on 17 September with 240 refugees on board. But it didn't get very far: before long it was intercepted by the Egyptian coastguard. The officials ordered the boat to stop, but the traffickers continued, probably out of fear. The coastguards then fired on the boat. Two of the refugees on board were killed and another seriously injured before the ship was forced to stop and the refugees taken back to shore.

Egypt is perhaps the only nation in the world that opens fire on refugees that are trying to leave the country. "Egypt is doing the dirty work for those European countries who've demanded that the nation on the Nile stop the wave of refugees coming via the sea route," explains Egyptian human rights lawyer Ahmad Nassar from Alexandria. Over the past two months, since the coastguard has been taking a tougher line, almost 1,000 refugees have been detained.

Shock and panic

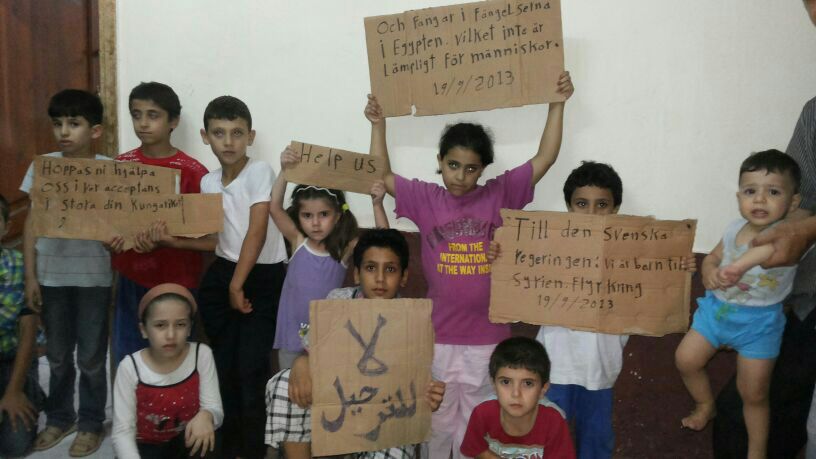

Some of those who survived the ill-fated trip on 17 September are being held at the Abukir's small police station. Just over 100 refugees, including 40 children, are being detained here. After much negotiation, a police officer finally opens the padlock securing the door. "I could get into trouble for this, but these people need help. Please write about them so that the Europeans understand what's going on here," he says.

The atmosphere here is more like that of a refugee camp than a police station. Washing hangs out to dry. One of the rooms serves to accommodate women and children, another is for the men.

Muntazir is a self-appointment spokesman for the group. He again tells the story of how they were intercepted by the coastguard. He shows mobile phone footage as evidence. The film also captures the moment after the boat was fired upon. Shock and panic are visible in the eyes of the refugees on board. And the mobile phone video repeatedly pans over the two corpses, that of a young man and a woman.

They also took photos. One shows the two dead bodies covered with ice blocks to prevent them decomposing in the heat. "We knew the crossing would be dangerous, but back home in Syria it was even more dangerous," Muntazir sums up his dilemma.

The 35-year-old is alone here. His wife and his daughter are still in Damascus, although their house in the Palestinian quarter of Yarmuk has in the meantime been destroyed. "My 12-year-old daughter started wetting the bed again out of fear at the almost daily bombardments. It was then I knew we had to leave," he says. Because he didn't have enough money for the whole family to make the crossing, he planned to be the first to go on ahead and try and fetch his family later.

If not illegally, then how?

Crossing the sea from Lebanon costs twice as much, so he came to Egypt. "I thank God that my family was not with me on that trip," he says in hindsight. "In Europe they only give us refugee status, if we manage to get there at all. But how are we supposed to get there, if not illegally via the sea route?" he asks and adds: "People need some kind of hope. We have to risk our lives to find a safe place." Muntazir has spent many years working as surgical assistant. He believes there is a need for people with this kind of experience in Europe.

Alaa, another refugee at the station with his wife and three children, says that just a few days before the ill-fated journey, he was still at the Austrian embassy in Cairo. He wanted to present his case there in the hope of being accepted. They didn't even get past the security official at the door. "That was the day we decided to try it illegally by sea. What other choice did we have?" He is interrupted by a woman holding a mobile phone with a photograph on it. The picture shows a ruined building. "That's our house. Are we supposed to go back there?" she asks.

European pressure on Egypt

"The Europeans give Syrian refugees few options to reach Europe through legal channels. Italy and Germany in particular are pressurizing Egypt to stop the boats," explains human rights lawyer Nassar. "The solution would be to officially accept more refugees in Europe and also help Syria's neighbours absorb them," says the activist. "These Syrian refugees are people who are being treated like animals."

The Egyptians will offer the people at the police station in Abukir the option of travelling on to a nation of their choice without a deportation stamp in their passport. The only two countries they can choose from are war-torn Syria and Lebanon. The latter nation is completely overwhelmed by the refugees. It is estimated that by the end of the year, 40 percent of people living in Lebanon could be Syrian refugees. Transposed to Germany, this would be equivalent to 32 million refugees; to Austria 3.2 million.

In a corner of the police station sits 13-year-old Ibrahim, staring into space. It was his mother who was shot dead on the boot – directly alongside him. He relates what happened, rattling off an account almost mechanically. He also reports that he sat next to her and cried. Now it's just him and his 21-year-old brother. The two were allowed to leave the station once for a short while: to bury their mother at a cemetery in Abukir.

Anyone sitting opposite Ibrahim quickly forgets what he actually wanted to ask, the boy's pain and shock are so tangible. What would Ibrahim liked to have done in Europe, if he, his brother and his mother had managed to get there? "It was my greatest wish just to go to school again," he replies briefly. And what did he want to be later? Ibrahim thinks for a moment: "I would most like to be a doctor," he says, "so that I can help other people."

Karim El-Gawhary

© Qantara.de 2013

Translated from the German by Nina Coon

Editor: Lewis Gropp/Qantara.de