The Hopes and Fears of the Exile

When asked about the situation in their native country, Syrians living in Germany are often very quick to change the subject. Very few are willing to say what they think, often because they are afraid of the Syrian Secret Service, which also has a network of agents in Germany and spies on the opposition movement in exile.

"Please don't use my name. And I would rather you didn't take photos," says Nadhiya (53), who hails from Aleppo and has lived in Germany for 23 years. She doesn't feel safe, even in a Western country. Hafez al-Assad, the father of Syria's current ruler, Bashar al-Assad, was in power when she lived in Syria. Even back then, Syrians couldn't speak their mind.

"There was no freedom of speech in Syria. Already when Hafez al-Assad was in power, we were afraid; the Secret Service was everywhere. If you expressed a critical opinion, they arrested you immediately." Those who kept their opinions to themselves were able to carve out a profession and climb the career ladder. "But we Sunnis were systematically put at a disadvantage," she adds.

The recurrent trauma of Hama

This disadvantageous situation culminated in 1982 in an uprising by the Sunni Muslim Brotherhood in Hama, which was brutally crushed by Hafez al-Assad. It is estimated that up to 30,000 people were killed in the process. After that, a deathly silence descended on the country.

But after the events in Tunisia last year, people in Syria began to take courage again and took to the streets. Nadhiya was delighted when she heard about the revolution in Tunisia and discussed the situation at length with her family. "At last an Arab country had started to rise up against a dictatorial ruler. We wanted that for Syrians too. Now, the violence has started again." Much of what has happened in recent weeks and months is reminiscent of the massacre in Hama.

Muhammad (27), who, like Nadhiya, hails from Aleppo, has been studying art in Germany for two years now. He can still recall the start of the protests quite clearly. "Initially I thought that that would not be possible in Syria. Everyone was afraid." Then came the demonstrations in Tunisia, and young people in Deraa began to spray anti-regime slogans on the walls. They were arrested by the security forces and held for days.

Opinions differ as to what happened next. Two very different versions are in circulation: that of the regime and that of the activists. The official version of events is that the young people – and in particular the 13-year-old Hamza al-Khatib – stood accused of wanting to rape soldiers' wives. Nadhiya is aghast at the very idea: "They were just children! They didn't want to harm anybody. They simply used slogans calling for more democracy and freedom." Then the Free Syrian Army was founded by soldiers who had deserted the army in order to protect the civilian population, which the army had already started firing on.

Assad's declaration of war against his own people

Muhammad's views contradict the official version put out by the Syrian authorities: "This incident demonstrates the brutality of the regime. Hamza al-Khatib was arrested. A week later, the family was allowed to come and pick up his remains. His penis had been cut off and he had been shot in the head." The murder of Hamza al-Khatib was a turning point; it changed the attitudes of many demonstrators.

Initially, Muhammad and his acquaintances waited for Bashar al-Assad to react to the demands for political reforms. Says Muhammad: "Had he given assurances that the incident would be investigated, called elections and revoked emergency laws, most people would still have supported him. I probably would have too." But could Assad have tolerated the protests instead of suppressing them? "Definitely," says Muhammad, "It was stupid and arrogant of Assad to refer to the demonstrators as terrorists from the word go."

Assad as the reformer the West initially took him for? "Yes. We hoped so. But this? With blood and violence?" Gradually, he says, the conflict escalated. The newly established Free Syrian Army responded to the terror of the Shabiha militia, who are loyal to the regime, with attacks. "The Shabiha terror was particularly bad in the city of Idlib," says Muhammad.

Hassan, a student from an Alawite border town, vehemently rejects this version of events. He has absolutely no sympathy with the revolution: "For me, the fighters of the so-called Free Syrian Army are the real terrorists; they have links to al-Qaeda. These Salafists don't want democracy!" He continues to stand by Bashar al-Assad: "The Western media's reports about atrocities are all lies!" says Hassan.

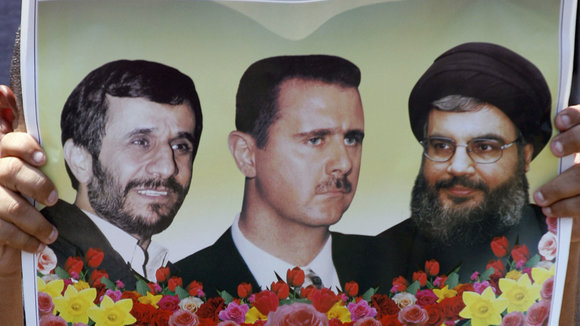

Supporters of the regime do not consider the members of the Free Syrian Army to be freedom fighters. As far as they are concerned, there is no revolution against Assad; it is much more a case of a "foreign conspiracy" to destabilise Syria. "They don't want freedom; they just want to cause chaos in order to destroy the Shia axis between Iran, Syria and Hezbollah," says Hassan. "It is a joke that Saudi Arabia of all places is demanding democracy for Syria. Shia are oppressed there, and the West says nothing about that."

The Salafist threat

Fadwa, a 22-year-old student of Islamic Studies, considers the opinions of Assad supporters – who can be found on every university campus in Germany – to be untenable. "The uprising is being supported by the entire Syrian people," she says. "There are also Alawites and Christians who are taking a stand against Assad." However, she does concede that the Salafists are already active in Syria.

Nadhiya points to a combat unit from her home town of Aleppo: "There is the so-called 'unity brigade' there. There are Islamists among them, but they don't in general play a major role. Student groups and other activists are much more active there." Although Fadwa does consider it possible that there are Salafists and al-Qaida supporters among the rebels, "they are only accepted insofar as they help to topple Assad. Once he is gone, no one will want them any more; the Syrians are not stupid."

Although Muhammad supports the revolution, he sees things differently: "The Salafists are very active in Aleppo in particular. They dominate the unity brigade in Aleppo. Although I am in favour of the overthrow of the regime, I am against the Salafists. And I think that the majority of Syrians share my opinion. The Shabiha and those who benefit from the regime have triggered a sectarian war with the appalling approach. It is often only about Shia or Alawites against Sunnis."

But Muhammad is also certain that many Shia and Christians are only supporting Assad because they are afraid. "A good friend of mine, a Shia, said to me: 'They'll send us to Iran if Assad is toppled!' My Christian acquaintances are also afraid of what might happen."

Hassan is afraid of a future without Bashar al-Assad and the Baath Party: "The terrorists all want to massacre the Alawites. Sure, there is an Alawite majority within the military; but there are Christians and Sunnis in there too." Although he would also like "that we all live peacefully side by side like we used to, but under Bashar al-Assad, who was only unable to implement his reforms because of the terrorists."

The stony path to democracy

As far as the future is concerned, most Syrians in Germany agree: "We want democracy!" Interestingly, all sides – both Assad opponents and supporters alike – speak of freedom and living peacefully side by side. Fadwa agrees: "I hope for real democracy and freedom of opinion where one can finally express an opinion without being locked away. But the main thing is that Bashar goes!"

But is it even possible to establish democracy in a country like Syria? For Muhammad, this question is not easy to answer: "I want neither a one-party state nor the Salafists. I want a Syria where Sunni, Shia, Druze, Alawites and Christians can live together and enjoy equal rights. Everyone should have the right to become president, regardless of his religious denomination. A Western-style democracy would be very difficult to achieve. But one like in Tunisia or maybe Turkey is definitely possible."

Fabian Schmidmeier

© Qantara.de 2012

Translated from the German by Aingeal Flanagan

Editor: Lewis Gropp/Qantara.de