Hakan Bicakci's disintegrating self

Since the Berlin-based publishing house, binooki Verlag, closed its doors, the word of emerging Turkish literature in German translation has gone noticeably quiet, at least where media attention is concerned. That is not to say there isn't just as much going on as there was before, especially as numerous small presses continue to commit their energies to this area. One such press, which has been active in this vein for many years, is Dagyeli Verlag, which published Sine Ergun's outstanding short story collection, “People Like Them” in 2022.

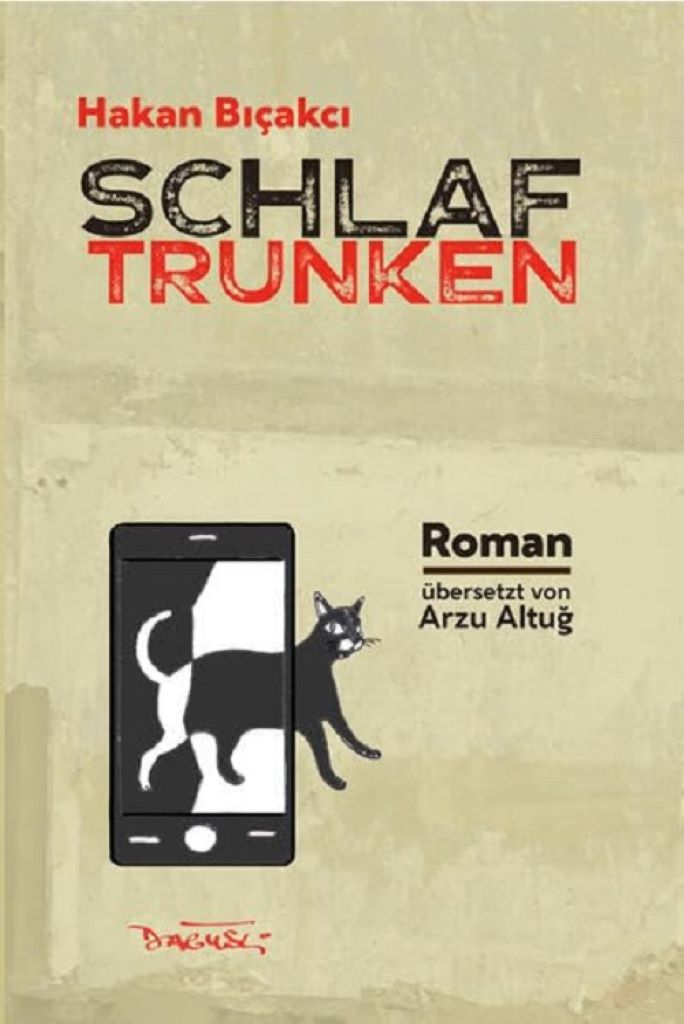

This was followed in 2023 by Hakan Bicakci's novel, “Schlaftrunken”, translated into German by Arzu Altug, an Istanbul novel that plays with genre while also providing acerbic literary commentary on the devastating developments along the Bosphorus.

"My eyes closed, the left one most of all," explains the book's protagonist, Kahraman Kara, as he steps out of the summery bustle and heat of the city and into his girlfriend Elif's apartment. She has left a note informing him about an enormous spider in the bedroom which has now disappeared under the bed and begins to haunt Kahraman's nightmares. "The roar from Istiklal Avenue reverberated in my ears. I felt like I had come from a battlefield where it was impossible to tell who was fighting whom. I fell asleep at once."

Old Istanbul has ceased to exist

But falling asleep is tricky. Kahraman usually suffers from a gruelling kind of insomnia and, as time passes, struggles to tell when he is awake and when he is asleep. He usually realises when eerie things happen, such as the instance with the spider.

He tries to focus on the details that aren't present in dreams, but it doesn't really help. His day-to-day life gives him no opportunity to relax. Kahraman is working on a book about Istanbul. The book is supposed to be a travel guide about unusual places: bookshops, cinemas, theatres, old patisseries.

The publisher promises broad circulation and translations into numerous languages. But disaster soon strikes during a conversation with the owner of Beyoglu's oldest bookshop: in the middle of a meticulously prepared interview, the man admits that the shop will soon be closing down, making the interview itself pointless.

And so it continues, in increasingly rapid succession: one location after another folds or is torn down, until all that remains is the dance school opposite Kahraman's apartment, in a district which is already being demolished by diggers and cranes, blocked off by construction site fences

It is clear that Kahraman's apartment will eventually be for the chop too. A police water cannon stands guard next to the building equipment. What are you supposed to write about, Kahraman wonders, when everything is disappearing and being ruthlessly gentrified? He can't even report on the new shops, because they don't last long either. And so, his publisher decides to throw a spanner in the works with a new idea: why not write a book, she says, about places that no longer exist? At least he won't have to scrap all the work he has done so far.

A journey through time to a lost world

Opinion in Turkey is divided over Orhan Pamuk. For some, the Nobel laureate is a shining star among Turkish writers. Others view him as a plagiarist and even denounce him as a traitor. His new novel has once again fanned the flames of the debate concerning the author and his work. Ceyda Nurtsch read the book

Everything is unravelling

But it doesn't help. Like the city around him, Kahraman Kara's life is gradually unravelling, it feels distorted and unreal, like a nightmare. Elif leaves him, his cat dies, then so does his grandmother, his mother moves to Germany and Kahraman finds himself in an apartment building on the Asian side where no one is allowed to live because it is not earthquake-proof and at risk of collapse.

To cap it all off, Kahraman is losing his face: he suddenly finds he looks completely different in photos and in the mirror, nothing like the picture on his ID card: “I glanced briefly at the photo Elif held out to me, wanting to look away, when something bizarre caught my attention. An ice floe broke inside me. It wasn't me in the photo. It was a man around my age, wearing my clothes and sleeping on my sofa with my cat. He looked like me, but he definitely wasn't me.”

Not only that, but he can no longer recognise his own voice. Bit by it, his crumbling reality and his nightmares merge, scenes of actual desperation meld with episodes that could be drawn straight from horror films, and this is where Bicakci's novel is particularly strong: with a mischievous wink, he switches seamlessly between genres, countering the heavy subject matter with plenty of humour, defying narrative ambiguity until the reader, like Kahraman himself, has little idea of what is real and what's not.

Kahraman, who has been making lists since his childhood (list of films, playlists, and, of course, lists to help structure his Istanbul book), now lists his dark dreams, checks himself into a sleep clinic, and everything goes from bad to worse.

Fast-paced storytelling

Hakan Bicakci was born in 1978 and studied economics. With fifteen novels to his name over the course of twenty years, he has developed a kind of cult status in Turkey, particularly among younger readers. He has received various literary prizes and was named one of Newsweek's Twenty Best Contemporary Turkish Writers.

His use of humour is reminiscent of authors such as Alper Caniguz, his work is defined by his fast-paced storytelling and use of short and snappy sentences full of outlandish ideas, not to mention the fact that he succeeds so brilliantly in bringing the hustle and bustle of Istanbul to life that you could be forgiven for thinking you were standing there yourself, right in the heart of it all.

© Qantara.de 2024

Translated from the German by Ayca Turkoglu