The fight to secure capital

Yemen’s conflict has contributed to a deteriorating economy, leading to significant tension and suffering within families and communities. Almost half the population has lost jobs, and public and private sector employment opportunities are scarce. The majority of families do not have an income, contributing to the country’s catastrophic humanitarian situation.

Although it has traditionally been men’s responsibility to provide for the family’s basic needs, many are fighting on the frontlines, have lost their jobs, are not receiving salaries, or are suffering from war-related disabilities. Women have come under enormous pressure, driven by need, to assume the role of breadwinners. However, conservative and patriarchal norms make it difficult for them to join the labour force. Normalised forms of economic gender-based violence, such as restricting women’s ability to save money, contribute to tension within communities.

Stepping up to these demands, many women have found solutions and turned negative situations into opportunities – by becoming entrepreneurs. Despite socially encoded norms, women-led businesses in Yemen have recently proliferated, with examples including home-based businesses or selling products through online platforms.

Women with cooking or sewing skills have started selling their products from home, while others have started businesses selling imported products, such as clothing, electronics, and cosmetics, that they can’t get because of the sea, air, and land blockade imposed by the Saudi-led coalition. Some have opened small shops to provide necessary services, such as mobile phone maintenance.

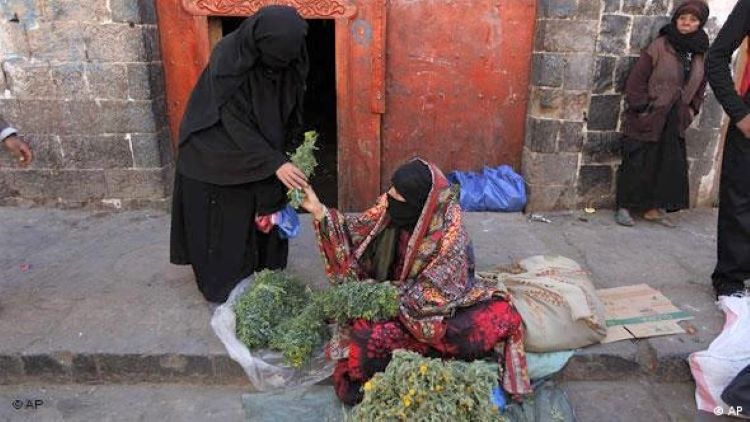

Unfortunately, many women, including internally displaced women and other minorities, have limited means to generate income. Some resort to selling clothes, tissues, or miscellaneous products on the streets, which frequently exposes them to violence and abuse.

For many, the obstacles to opening a business are too high. Women entrepreneurs note that even if women overcome social barriers, they do not have access to the necessary financial resources. With many families left without any source of income, savings, assets, a job opportunity, or any other means to access finance, securing capital remains a challenge.

Islamic micro-financing services and the community-based fund, Jami’yaat, present potential solutions. But socio-cultural norms, religious beliefs, and the wider economic situation prevent many women from seeking financial opportunities outside of their families. According to an assessment conducted in Sana’a City, "the main source of capital to starting a business was from personal savings and family", indicating that a large gap exists in the financial sector.

With so much economic potential ready to be released, there is an urgent need for financial institutions, such as microfinance institutions (MFIs), to increase support for women entrepreneurs, especially those who do not have alternatives to loans to secure capital.

Banks viewed with suspicion

In Yemen there is a lack of knowledge about the banking system and its services, contributing to many people, particularly women, not having bank accounts. In 2014, less than 2 percent of Yemeni women had an account with a financial institution – very low compared to other Arab countries.

Although by law Yemeni women have the right to own property and business and to engage in financial transactions, including taking out loans, significant barriers still prevent women from approaching financial institutions such as banks and MFIs and taking out loans to secure start-up business capital.

The wider culture, with traditions and customs that define women’s gender roles and their interactions with men, creates obstacles for women who want to approach banks. For instance, many women must gain permission from their male guardians. Furthermore, the societal culture encourages people to borrow money from a relative, rather than a bank.

Many Yemenis prefer to invest most of their savings in assets such as gold ornaments, houses and land rather than a bank account. Even in terms of security, most people believe that it is safer and simply easier to save money in cash at home. This belief was reinforced by banking practices at the beginning of the conflict.

As banks turned down withdrawal requests or asked for smaller amounts to be withdrawn due to a lack of liquidity and devaluation of the local currency, many lost their trust in banks. Moreover, stories of militias seizing or freezing entire bank business accounts increased fears of depositing savings in banks. However, with the conflict continuing and widespread insecurity and impunity, it also became riskier to keep savings at home.

An additional barrier is the Islamic attitude towards interest ('riba'), a significant cause of suspicion and mistrust in financial institutions. Islamic principles prohibit interest rates on loans and deposits, which deters many Yemenis from depositing their money or taking loans from banks. In some especially conservative communities, there are even more doubts about financial institutions, including Islamic banks.

When micro-financing was introduced by the Social Fund for Development in 1997, much of Yemeni society rejected it, while religious figures, such as imams, denounced it and prohibited people from taking micro-credits. But, after persistence in providing these services, over time this negative perception has changed, and microfinance has gained some level of acceptance.

Accessing formal finance a problem

Even if women get past the societal suspicions of banks, they face other hurdles. Credit requirements prevent many from seeking finance opportunities from financial institutions. Conventional and Islamic banks embed substantial collateral requirements, making it prohibitive for most women to apply for loans. High interest rates are a barrier, firstly because women entrepreneurs cannot afford them and, secondly, because for many it goes against their religion.

While Islamic banks can fill this gap as they provide alternatives to interest rates in line with Islamic principles, women are still unlikely to approach them because loan collateral requirements remain similar to conventional banks. Consequently, banks are one of the least favoured options to obtain business start-up loans.

Most MFIs offer different types of loans with lower interest rates while adhering to Islamic principles. Yet, MFIs still have collateral requirements, especially on individual loans, which many women cannot meet. These requirements differ between MFIs; for example, guarantees in the form of deposits, jewellery, salaries, and bank letters.

Networking is one potential way around this obstacle, with support available for collateral requirements, such as facilitating guarantees, needed by most MFIs and banks. However, social restrictions affecting women lead to limited access to business networks; restrictions include a prohibition on attending social gatherings of men where much business takes place.

Jami’yaat: an alternative means of finance

Given the obstacles to accessing formal financial institutions, informal mechanisms for lending and saving are common amongst women. Most women entrepreneurs rely on their own or their family savings and resources. Examples include borrowing money from a family member or obtaining cash in exchange for gold (i.e. jewellery). Often women acquire most of their gold by dowry before getting married.

Within Yemeni culture, a woman’s gold is considered her financial security and insurance. However, some women entrepreneurs pawn or sell any gold they have as a last resort to secure some or all the capital needed for their business. In other cases, women put aside small sums of money over an extended time, from their personal income if they had a job, or from money their husband gave them for household or personal expenses.

Jami’ya is a well-known informal finance arrangement in Yemen and across many Arab countries. It is a membership-based fund, to which each member regularly pays a fixed amount of money, mostly every month. The fund’s accumulated balance is paid to a single member at the end of each agreed period (e.g. end of the month) until all members receive a monthly share.

Fund members may be family members, co-workers, neighbours or friends, with some participants from different social circles if they are vouched for by trusted members. Women research participants stated that Jami’yaat are popular within their communities, and they prefer them to take loans from formal financial institutions for several reasons.

First, Jami’yaat do not require any interest rate or substantial collateral; rather, members/participants have trust and act as a guarantee for each other, reducing the risk of defaults. Second, any woman can initiate her own Jami’ya and allow people she trusts to participate. Third, participants decide together who will be paid out first, for example, in terms of necessity, or randomly, or alphabetically. It is common for participants to exchange turns later on between themselves, and everyone is free to spend the money the way they want.

As the current economic crisis, including the widely suspended salaries, is making it increasingly difficult for community members to participate in a shared fund, women say that they plan to continue this practice once they receive salaries again. Interestingly, Jami’yaat are still operating among some micro and small business owners, owned by both men and women, to secure the funds needed to improve and sustain their businesses.

More networking by MFIs and women entrepreneurs

Women entrepreneurs provide income to families that might otherwise have been sought at the frontlines. Their economic participation introduces opportunities for members of local communities to collaborate, and ultimately sustain each other. Therefore, there needs to be more financial resources and wider societal support to help women who have great ideas to open businesses and be active in public and economic life. This support should be cemented through the establishment of more business networks involving women entrepreneurs to provide each other and new women-run start-ups with the necessary assistance.

So far, women’s roles in the economy as entrepreneurs have been accompanied by many difficulties, securing capital being one of the most critical. MFIs, especially informal institutions, are plausible sources of finance. However, they face several challenges, including "insufficient funds, limited outreach and poor infrastructure". To support women by encouraging them to access MFI services, MFIs could, for example, ease credit requirements. Conventional banks, the government and international donors could support MFIs in this.

Also, civil society organisations and international/non-governmental organisations could promote awareness campaigns and workshops about the financial sector and microfinance opportunities, to achieve financial inclusion and normalise bank and MFI accounts for each Yemeni woman. These campaigns could also bring the dual benefit of reducing excessive suspicion around interest rates, specifically in the case of Islamic MFIs.

Necessity has shown that Jami’yaat are successful as a method of social solidarity and have supported many people, including women entrepreneurs. Thus, women entrepreneurs can establish Jami’yaat so that each member can periodically receive her share of the fund and help women in the community who need start-up capital. This can assist in creating multiple job opportunities and sources of income for many families.

Jami’yaat should be supported and expanded, offered either as an MFI product or through the local postal service. With the right support, Yemeni women’s entrepreneurial spirit, already evident, could be unleashed still further.

Amal Abdullah

This article was originally published by the Yemen Policy Center, which is funded by the German Foreign Office.

Amal Abdullah is a Research Fellow at the Yemen Policy Center. She has published analyses on YPC’s Majlis blog and served as a translator for YPC projects and several other organisations, including the UN Human Rights Training and the Documentation Centre for South West Asia and the Arab Region. She has written reports on various subjects, including the effect of women’s education on fertility rates in Yemen; her interests lie in development, family economics and women’s issues.