The Sahrawis are fed up with waiting

Omar is seated on a carpet in his father's tent. He was born here, the 21-year-old says – here in the refugee camp of Awserd in the Algerian part of the Sahara. All around there is only desert, no water and farming is impossible. "It's not easy to live here," says Omar. "There is no future here."

Awserd alone houses some 50,000 people – in tents, mud shacks and brick houses. Omar lives with his parents and five siblings somewhere between the camp's areas two and three. He attended school until he turned 18 and went on to an Algerian university. But that did not last long. "I had problems because I'm the eldest in the family and the family needs me to earn money and much more. So I had to give up my studies. There is no hope. There is no hope."

People in the camps have tried to make the best out of their situation. They set up their own urban districts, communities and regions. Schooling, health care and the distribution of relief supplies has to be organised. The camp has been in existence since the outbreak of the civil war.

No light at the end of the tunnel

Now, after more than four decades of conflict, hopelessness is spreading, says the governor of Awserd, Mariem Salek Hamda. The food aid supply has declined, infant mortality is double that of Europe and water is limited to 10 litres per day.

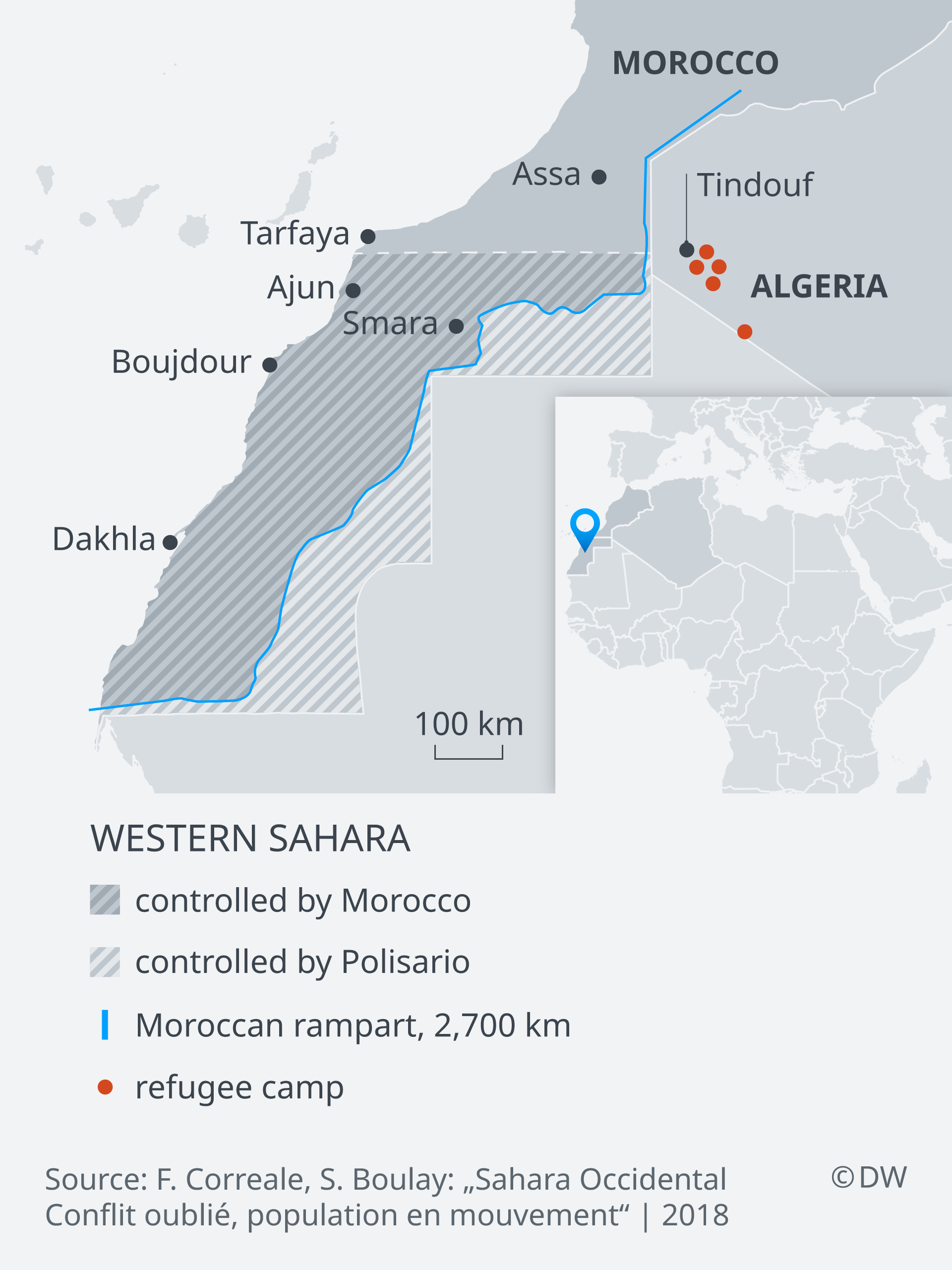

"The young people are in despair because in this situation, in which we have been for more than 43 years, they see no light at the end of the tunnel," Hamda says. She points to the ceasefire of 1991. A United Nations mission has since been monitoring the zone adjacent to Morocco. It should actually be overseeing a referendum on independence for Western Sahara.

"But since 1991 the young people born here see no solution on the horizon. With this standby situation of 27 years – with no peace or war and doubt and mistrust of the UN – this situation arises in the occupied areas. One hears daily about a mother, sister or brother being kidnapped and abused. All this breeds dissatisfaction that can lead to anything," Hamda says.

Some people in the camps make no secret of where the dissatisfaction can lead. Among them is Addou al-Hadj who leads tours at the Museum of Resistance in the nearby Smara camp. "We are tired of waiting," he says. "We are fed up with the status quo. No one has made a move in 43 years; we have waited for more than 27 years for a resolution via the UN. We are peace-loving people, but when nothing is resolved, we are prepared to take up arms."

Independence or referendum

Many people of Western Sahara want independence for their homeland, or at least this long-promised referendum. Mohamed Salem Salek, the foreign minister of the government-in-exile, knows that. His office is half an hour's drive from Awserd, in Rabuni – the seat of the Sahrawi Arab Democratic Republic.

Western Sahara is a member of the African Union but only few countries recognise it as independent. "How can one convince the Sahrawi people to hold out and accept that the UN is working on a referendum with which they can exercise their right to self-determination?" asks Salek. "The people say: 'No, they are just playing games with us."

As night falls in Awserd, Omar makes his way home from the little grocery business where he sells water, a little meat and tea to those who can afford it. His eyes wander to the starry heavens. "The most beautiful sky in the world," he says.

All the same, he sometimes dreams of going far away, to Europe. He has lived many years in difficult conditions, he says. His children should have a chance of living a normal life.

Hugo Flottat-Talon

© Deutsche Welle 2019