A race against time

Over the last three decades, various initiatives and proposals have been launched to save Beirut′s endangered buildings, yet to no avail. The greed of real-estate moguls is not only having a dramatic impact on the appearance of the city′s historic Levantine neighbourhoods, but also on structures dating from its cosmopolitan heyday of the early 20th century.

In 1996, the Lebanese Ministry of Culture commissioned a survey by the Association for Protecting Natural Sites and Old Buildings (APSAD) to list the capital′s historically valuable buildings. Although APSAD classified 1,051 endangered buildings in need of protection, Beirut′s old houses continued to vanish apace.

In 1997, more than half of the buildings were removed from the list by the government. A year later, the number of endangered houses was reduced to 209. As of today, while developers inflict irreversible damage on the city′s heritage, civil activists are the only ones protecting the vanishing beauties of Beirut and raising awareness about their city′s hidden gems.

Tabula rasa

Post-war demolition began in downtown Beirut. The quarter saw some of the fiercest fighting during the civil war and most of its old souks and the adjacent Martyrs′ Square were destroyed as a result. But what proved the final death knell for the centre of the capital was Solidere.

Solidere, a development company founded by the first Lebanese post-civil war Prime Minister Rafikh Hariri, razed the district to the ground, replacing it with a soulless, ostentatious development. ″This area belongs to Solidere and all the changes in this area have been dictated by this company,″ says Mazen Haidar, a Lebanese conservation architect and vice-principal of the School of Architecture at the Academie Libanaise des Beaux-Arts (ALBA).

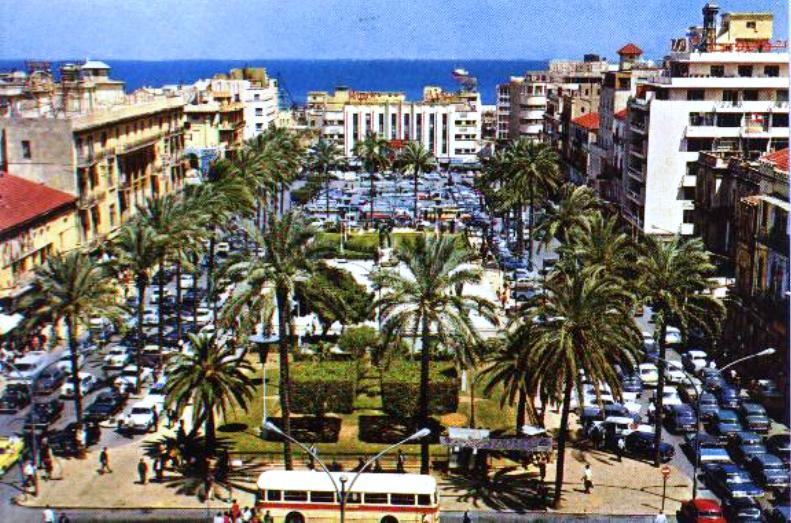

According to Haidar, Martyrs′ Square, in the heart of Beirut, was a landmark of the Lebanese hybrid identity. ″The square didn′t have a homogeneous character – indeed it was a true reflection of the Lebanese identity. It included buildings from the 19th century, the French era and the modern time. The decision by Solidere to demolish Martyr′s Square resulted in the eradication of Lebanon′s pre-civil war history,″ Haidar adds.

These days, every trace of downtown Beirut is gone, but the city′s architectural heritage is still alive and scattered across the capital. Saving Beirut′s 300-year-old Red House, breathing new life into the 19th century Rose House, turning the Barakat Building from the early 1920′s into a museum and preserving the Heneineh Palace are examples of successful campaigns to protect the city′s once majestic houses.

The biggest obstacle that preservation activists face in Lebanon is how to achieve results in a country plagued by political dysfunction. Lebanon has been without a president since May 2014, the last parliamentary elections were held in 2009 and the government is currently unable to solve Beirut′s garbage crisis.

Activism in a vacuum

On Martyrs′ Square, the skyline is punctuated by a dozen or so cranes, like the arms of a gigantic octopus attacking its prey.

″There is no law that protects the Lebanese heritage,″ says Joseph Haddad, the secretary general of the Association for the Protection of the Lebanese Heritage (APLH). ″The only law we have is an architectural law from 1933. Even this law is not Lebanese. It was introduced by the French during their mandate in Lebanon.″

In 2010, the APLH was launched as a Facebook page to raise awareness about the dilapidated state of Beirut′s architectural heritage. The group organised several sit-ins to protect buildings in danger of demolition, but soon expanded its activities to include education and the documentation of Lebanon′s architectural and cultural heritage.

According to Haddad, raising awareness is one of the main focuses of the APLH. ″Culture, history and identity are like good health. You don′t realise how important they are until they′re gone,″ Haddad says. ″We need to constantly remind the Lebanese people of the importance of these factors, promoting the concept in a creative and festive way. We want people to celebrate their culture and heritage.″

Today, when Haddad looks back at six years of activism in Beirut, he points out that one of the highlights of APLH was the launching of a crowd-map to document every archaeological site and piece of architectural heritage in Lebanon. ″With this crowd-map, even if property developers demolish a building, we will retain its records and memory,″ Haddad says.

Haidar strikes a similar tone when expressing the importance of education and documentation in preserving Lebanon′s architectural heritage. ″To raise awareness, we need to work steadily and without getting over-excited,″ he says. ″For a start, the existing heritage should be documented and the citizens made aware of what they have.″

In co-operation with the non-profit institute of the Arab Centre for Architecture, Haidar has organised conferences, workshops and walking tours in an attempt to introduce the modern Arab-built heritage of Beirut to its citizens. ″If people could understand the value of these landmarks, then we might convince their owners or political stakeholders to halt the demolition,″ he says.

During the civil war, Beirut and its people were divided – East versus West. Now, 26 years after the end of the civil war, people of Beirut are still hesitant to go from one side to the other. That′s why activists like Haidar believe people need to look at Beirut from a new perspective. ″With the Beirut walking tours, we aim to provide a new window for people to discover their city and see it from a different angle.″

Changiz M. Varzi

© Qantara.de 2016