Of infernal proportions

If there is one thing North Africa and the Middle East are not short of it is crises. The wars raging in the Fertile Crescent, in Yemen and Libya have become as depressingly familiar as the dangerous, interminable slow-burn of the Israeli-Palestinian conflict.

Turkey is gradually being transformed into a dictatorship, while Egypt, a country which has already returned to that state, is facing bankruptcy. For decades now, the former "breadbasket" on the Nile has not been producing enough food to feed its rapidly growing population. Now the government can no longer afford to pay for the necessary grain imports. Even in apparently stable countries, like Morocco, the smallest of sparks may ignite flames of protest.

All of this is more than enough justification for a high level of despondency. Added to these political-social conditions, however, there is another, more subtly insidious blight. Neither dramatic nor sensational, it is a gradual, barely perceptible affliction, so gradual that, in the short-term, the small changes that characterise it seem normal. The term "creeping normalcy", has been used by the US scientist Jared Diamond to describe the inability of people even to recognise the problem.

From Casablanca to Dubai, summers have never been cool. Anyone foolhardy enough to have taken to the beach in the Red Sea resort of Dahab in July without a sunshade, visited the pyramids at Giza in the heat of the mid-day sun, or the Chehl-Sotun palace at Isfahan, even those who dared to take a hundred-metre walk to cross the street in Doha can testify to that. A closer look at the figures makes it clear that temperatures across North Africa and the Middle East are on the rise, especially in the summer months.

Large areas uninhabitable

Scientists from the Max Planck Institute for Chemistry have been taking a closer look. Their predictions make for depressing reading. Using computer simulations, they are predicting that there will be an average rise in temperature in the region of around four degrees celsius by mid-century. This would mean the number of extremely hot days, with maximum temperatures of 46 degrees and above, rising five-fold, from 16 at present to 80 days a year. Night-time temperatures would not sink below 30 degrees. "The climate in many parts of the North Africa and the Middle East could change so drastically in the coming decades that these areas would become hostile to life," says atmospheric researcher Jos Lelieveld, leader of the study published earlier this year. There is a real danger of these areas becoming "uninhabitable" for many creatures, including humanity.

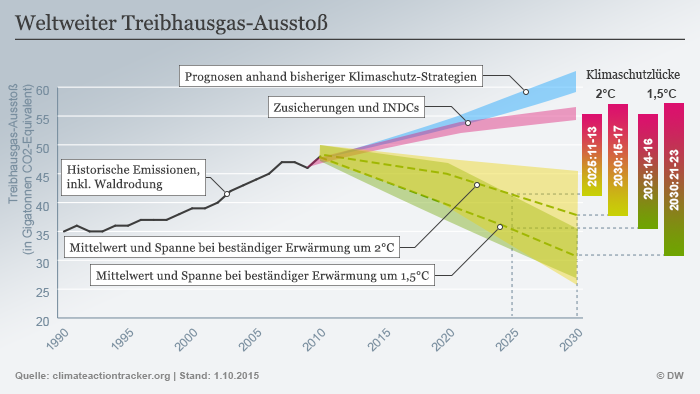

Describing such a "blight" as an act of God, is of course not accurate. This horror scenario is after all the result of man-made global warming. In the 200 or so years that have elapsed since the advent of industrialisation, we have released too much carbon dioxide into the air and by doing so, increased the natural greenhouse effect.

The rise in temperature, however, is not uniformly distributed across the globe. It is greater in some regions than in others: in the Arctic, for example, or in the arid and semi-arid regions of North Africa and the Middle East.

Even today, the increase in temperatures is causing more dust to be stirred up. According to the Max Planck Institute, fine dust pollution in Saudi Arabia, Iraq and Syria has increased by 70 percent during the last two decades as a result.

Under cover of a sandstorm

This is happening even without the bombers and howitzers that are currently pounding the concrete of Aleppo and Falluja to dust. There is no doubt that an interaction between political events and climate change in North Africa and the Middle East exists. In May 2015, an "IS" battalion captured the Iraqi city of Ramadi under cover of a sand and duststorm that prevented anti-IS coalition fighter aircraft from taking off. And just a little further back in time, the four years of drought prior to 2011 was a factor in the dissatisfaction and despair of the rural population in Syria, which was one of the contributing causes of the uprising against the Assad regime.

This month will see the world's climate experts coming together in Marrakesh. The onus will then be on each of the individual countries to explain how they intend to fulfil the commitment they made in Paris – to limit the average increase in global temperature to a maximum of two degrees. The bad news for the city of Marrakesh and for the countries on its latitude, is that even if the world manages to reduce CO2 emissions, the populations of North Africa and the Middle East, in the coming generation, will experience an average rise in temperature of 4 degrees compared to pre-industrial times. Should greenhouse gas emissions continue at present levels (the so-called "business-as-usual-scenario"), scientists are predicting a total of up to 200 extremely hot days a year in the region by the end of the century.

Discussions of the deplorable political conditions in the Arab world tend to come down to the relative degrees of responsibility between outside aggression and the region's own self-destructive tendencies. People question whether colonialism is to blame for the decline "or the people themselves are at fault".

Climate change in North Africa and the Middle East will no doubt add more fuel to the fire. The oil exporting countries, particularly Saudi Arabia, have always tended to drag their feet at climate conferences, putting their economic interests before the need to reduce greenhouse gas emissions. Through an excessive consumption of fossil fuels, their customers in North America, Europe, China and Japan contribute to global warming more than anyone.

The expected new discussion on the question of whom to blame for the climate-induced uninhabitability of large areas of North Africa and the Middle East is as unlikely to remain a mere theoretical exercise as the old dispute on the consequences of colonialism.

Anyone seeking more confirmation need look no further than the withered pistachio plantations in Iran, the decaying groves of date palms near Marrakesh, or the sandstorms in Baghdad. There are warning signs aplenty. Around 550 million people live in the countries of the Middle East and North Africa. Professor Lelieveld and his team believe that "sooner or later, many may have to leave the region."

From the perspective of the West, should this happen, then in the words of leading German climatologist Hans Joachim Schellnhuber, "Christian charity will seem, at best, no more than an ethical warm-up."

Stefan Buchen

©Qantara.de 2016

Translated from the German by Ron Walker