Road movie against patriarchy

There are numerous driving scenes in Three Faces. It is reminiscent of one of Jafar Panahi's earlier works, Taxi, that earned the Iranian filmmaker the Golden Bear at the 2015 Berlin International Film Festival.

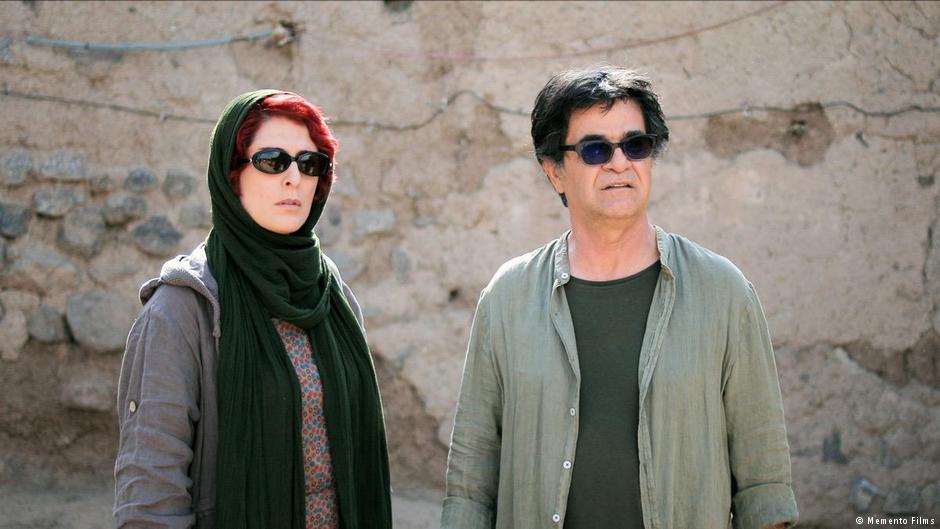

Once again, the director sits behind the wheel. This time, he's joined by an actress called Behnaz Jafari — the actual name of the actress co-starring in the movie.

The two of them are responding to a cry for help from a young girl, Marziyeh Rezaei, who lives in a remote region of Iran.

She sent a video message to Jafari saying that she wanted to study acting and that she had even been accepted into an acting school. But her parents, preferring to marry her off in the traditional way, wouldn't allow her become an actress.

When the famous actress doesn't react to her message, Marziyeh becomes desperate. She had placed great hope in contacting Behnaz Jafari, an actress who managed to become a star despite the country's patriarchal structures. In the country's capital, Tehran, women enjoy more freedom than their counterparts in rural areas.

The final images in Marziyeh's video message show her putting a rope around her neck and jumping into the unknown.

A tribute to female actresses

Behnaz Jafari and Jafar Panahi head off to a village near the border with Azerbaijan to find out whether the young woman really did commit suicide. She didn't. What she did manage to do, however, was to lure Behnaz Jafari into her village.

That's where viewers encounter the third "face" that plays an important role in this film – albeit only as a silhouette: the face of Shahrzad. Before the Iranian Revolution, Shahrzad was a famous actress and a celebrted diva. Although still known in present-day Iran, she was forbidden to act in films from the late 1970s onwards. Nowadays, she lives in a remote area of the country, lonely and ostracised.

Panahi has devoted his latest work to Iranian actresses, and those who dream of becoming one. Under the present regime, they are seen as "fallen women" and consequently outlawed, marginalised and discriminated against. In Three Faces, however, three generations of women take a stand against their treatment, just like Panahi himself: even though he was banned from directing films eight years ago, he has since managed to produce four works.

Minimalist camera work

Under such circumstances, the director was once again forced to film on a shoestring: with only one assistant and one camera. Despite it being a highly sensitive and flexible model, the set-up restricts the complexity of the shots. That's why Panahi made maximum use of his female protagonists, largely remaining in the background himself.

He filmed in three villages in northern Iran where his parents and grandparents once lived, and where nobody would inform the regime in Tehran about his defiance of his occupational ban.

But the film is more than just a hidden form of criticism of the political situation in his home country or the traditional attitudes of the inhabitants of these villages. It is also a colourful and humorous portrayal of life in Iran's rural areas, depicting numerous funny situations and traditional customs.

On one occasion, he is given the foreskin of a little boy, preserved in salt, and asked to bury it in a powerful place in Tehran, so that the boy will grow up to be something great.

And then there's a narrow mountain road that is only wide enough for one car to pass at a time: a complicated honking ritual determines which car may pass first.

When Marziyeh sets out to widen the road, equipped with a pickaxe and shovel, the village community steps in, saying that this is no kind of work for a girl. Then traffic grinds to a halt when a bull lies down on the road, making it impassable.

Regardless of whether the scene is an allusion to the regime, Panahi enchanted viewers in Cannes with his wonderful stories. The Iranian director would have loved to witness his film's world premiere in Cannes, but the Iranian government has banned him not only from filmmaking, but also from travelling. Not even the intervention of the French festival organisers could change that.

That's why the seat reserved for him at the premiere remained empty. In spite of that, or because of that, he received frenetic applause.

Against all odds, he has managed once again to secretly produce a film and have it smuggled out of the country.

Another aspect of his work is that Panahi has produced a feminist manifesto for the #MeToo era. Without accusing men of anything, he shows solidarity with women. For the first time since his ban, several names appear in the end credits. That may be normal in other countries, but in Iran it is as a courageous gesture. After all, the people mentioned there admit that they have worked with an outlawed director. It's a kind of protest that makes people hope for a better future.

Suzanne Cords

© Deutsche Welle/Qantara.de 2018