Flashback to a childhood in Tehran

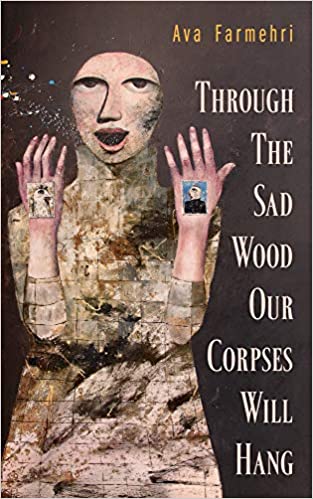

"Through the sad wood our corpses will hang". It could be the title of an American horror novel. Or something by Shakespeare. But it’s actually a quote from Dante’s Inferno, the first part of the Divine Comedy. It’s also the title of Ava Farmehri’s debut novel, originally published in Canada in 2017, and now available in German, translated by Sonja Finck. It is a title that presents the reader with a puzzle, making you wonder again and again over the course of the book what it actually has to do with the story.

Ava Farmehri is a pen name – and, so far, a well-guarded one. There is not much to be learned about the author, other than that she grew up "in the Middle East surrounded by books, cats and war", as the novel’s blurb tells us. But there is a lot of other information in the pages of this book, in the stories, observations and anecdotes from an Iranian childhood during the 1980s and 90s. Too much that is too genuine and realistic for it all to be simply fiction. You get a sense that there is a great deal of autobiographical content here, though possibly fictionalised. And the background is in any case as real as it gets..

Another book, then, by an Iranian author about the Shah, the Islamic Revolution, the Iran-Iraq war, Islamism and prison; another exile story from the generation of the banished?

It’s a question you ask yourself on the first pages, of course, with another sigh, because the few books by Iranian authors to be published in translation, especially in Germany, are so monothematic – which of course is not a charge against them, but against the commissioning publishers.

Most of these books are worth reading, but they do give the (entirely wrong) impression that no one in Iran writes about anything else.

Born with the Islamic Revolution

And this is how it begins: the protagonist, Sheyda, stands in the dock as a death sentence is handed down to her. The case seems clear: she has been found guilty of murdering her mother, and even confessed to the crime as soon as she was arrested in the snow-covered winter garden of her parents’ house.

It is the end of 1999, and Sheyda is 20 years old. She was born in the fateful year of the Islamic Revolution; she has heard a lot about conditions in Iran’s prisons, and now she’s experiencing them first-hand.

Locked up in a communal cell with other women, always ordered around by the sadistic female guards, always with the fear of being taken from the cell at night and raped. But unlike her fellow inmates, Sheyda is astonishingly calm, and seems to be accepting her fate stoically – after all, she says, she is guilty, so this is how it must be.

But is that true? When she is transferred to a single cell, she knows her time will soon be up. She begins to remember, casting her mind back over her short life one more time.

She was always an oddball, had no friends, was defiant and rebellious at school and often brought her parents to the brink of despair, in part because she still wet the bed at the age of seven and no doctor could suggest a solution to the problem.

Even as a little girl she steals things, is a notorious liar and escapes from an unloved, narrow reality into a dream world, where she creates an alter ego named after Dante’s Beatrice, who has a lot in common with her literary role model. She is secretly in love with Mustafa, the boy next door, who gives her English lessons and is a lot older than her. When he realises what lies behind Sheyda’s daily eagerness to learn, he is completely taken aback.

Her own way of rebelling

When the first blossoms of puberty begin to appear, Sheyda throws herself into affairs with much older men. It is her way of rebelling against a system that is increasingly curtailing women’s freedoms. A system that is admittedly scarcely addressed directly in the majority of the book, though its effects on people’s lives can be felt in almost every line.

Once, Sheyda imagines being pardoned and released, and a journalist asking her what she feels. "Nothing," she replies. "Nothing at all." An allusion to Khomeini’s return to Tehran in 1979, when he chose the same words.

[embed:render:embedded:node:24587]

You sometimes forget, while reading, that this is a flashback lasting almost 200 pages. The narrative returns only infrequently to the prison-present for a few pages, before quickly diving back into the past.

Then the story meanders through memories that seem to lead associatively from one to the next – of her grandmother, or her always-unlucky Aunt Bahar; the terrible accident in which her father is killed; the eccentric neighbour and her beloved chickens; the endless days of reading during Sheyda’s part-time job in a bookshop (where she also discovers Dante’s Beatrice, whom she puts on like a cloak, retrospectively, over her childish self).

It is above all Sheyda’s voice, the blacker-than-black humour with which she repeatedly causes offence, and all her odd quirks that make this protagonist so memorable.

And yet, you still keep asking yourself: where is all this going? Is it going anywhere at all? Are the prison and the death sentence just a narrative device to justify all the childhood memories? Ava Farmehri leaves the reader in the dark about this for a long time. Or more precisely: she leaves us "in the sad wood" of the book’s title, the meaning of which is only revealed right at the end.

It is only on the final three pages that you realise what the author is really doing here, how cleverly she has constructed this book and how calculated each one of these often seemingly unconnected flashbacks is. You understand where all these threads are leading very late – too late. For at that point, Farmehri pulls the rug out from under her readers with such force that you are left speechless.

© Qantara.de 2021

Translated from the German by Ruth Martin