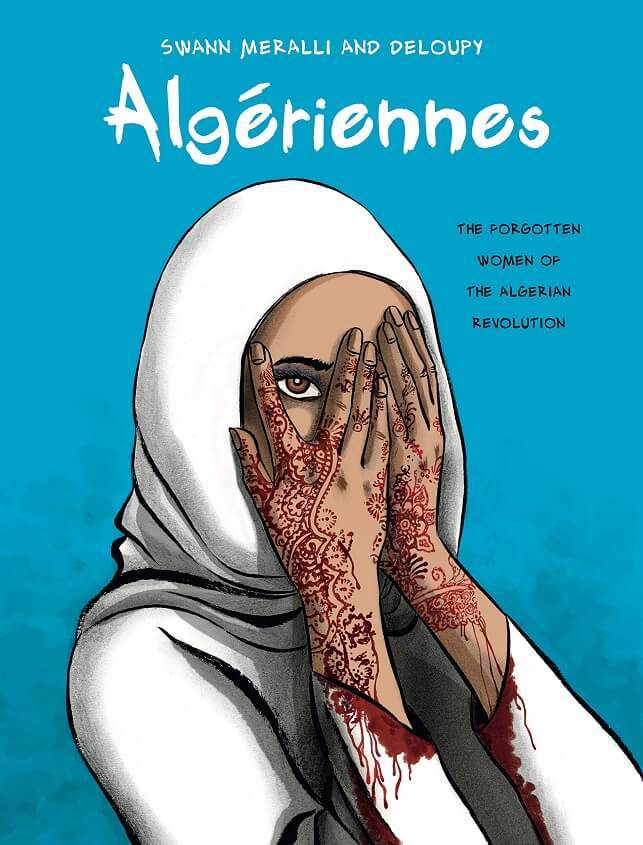

The bravery and resilience of Algeria's "mujahidates"

Algeriennes chooses, as the title suggests, to focus on the involvement of women in the Algerian conflict. While much is published about women bearing the brunt of suffering on the home front or suffering abuse at the hands of conquering soldiers, it is rare that the stories of women who actively participated in a conflict are told. The fact that the personal accounts related in the graphic novel also happen to be true – or, at least, are based on the experiences of actual people – make it even more gripping.

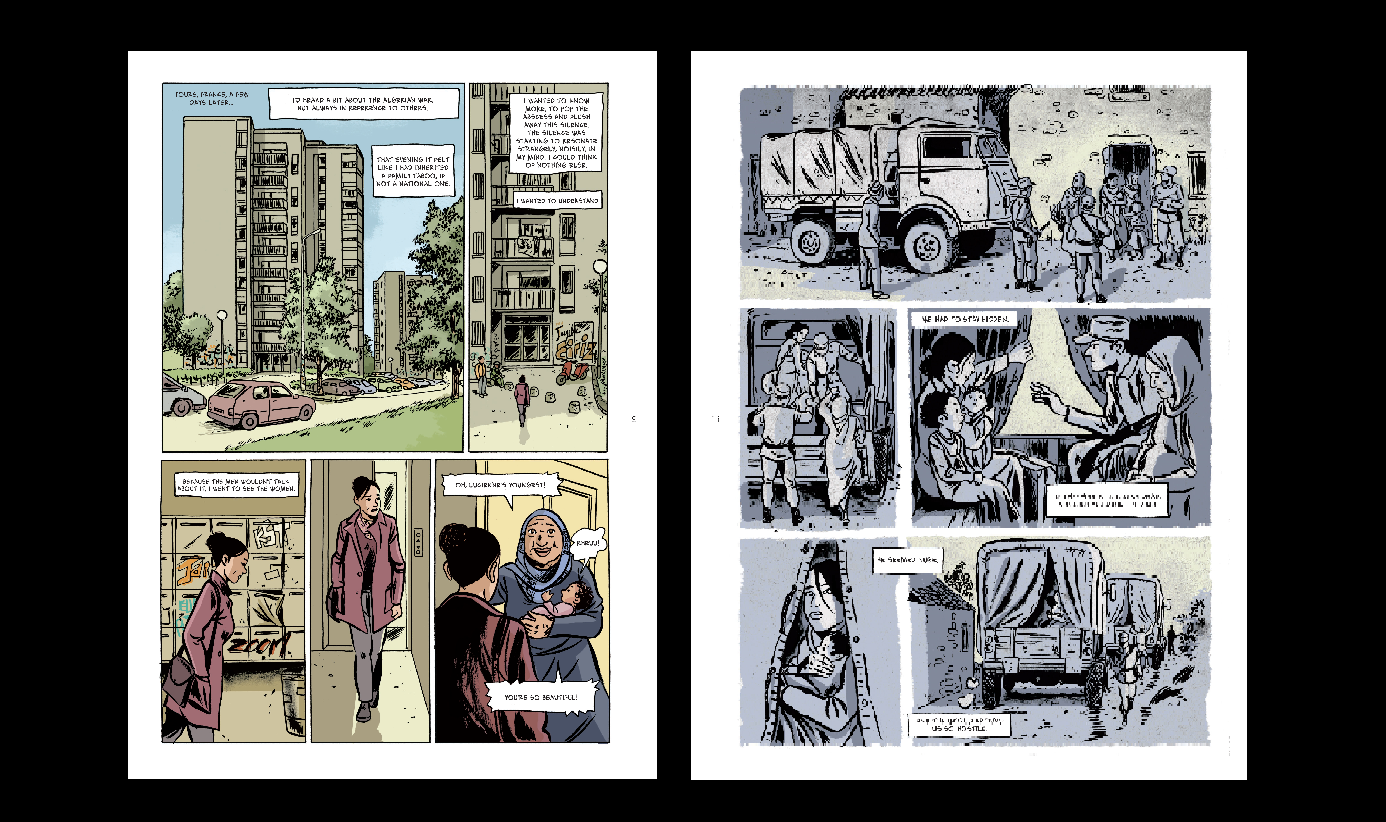

We are led into the novel by Beatrice, whose father served in the Algerian war as a French soldier. She stumbles across a fascinating article about the Algerian war, which feeds her a quantity of titbits, including the fact there's a special term for the children of French soldiers who served: "enfant d'appele". Yet, when she tries to broach the subject of the war with her father, he refuses to talk.

A journey of discovery

Her mother does, however, tell her a little bit about their time in Algeria, including how when she was wheeling Beatrice's sister in her pram, they were nearly injured by a terrorist bomb exploding in a public square. She also tells her daughter that, if she wants to know more, she should talk to an Algerian friend of hers. Thus begins Beatrice's long journey to discover the truth of the Algerian conflict.

The friend of her mother's turns out to be one of the Algerians who supported French rule and had to flee for their lives, abandoning their homes and lives.

Originally her father had fought for the rebels, but when a rival rebel group beheaded his brother, he became a Harkis – the name given to those who supported the French. Fearing retaliation after the war, they were evacuated to France.

On hearing her story Beatrice decides to travel to Algeria to see what she can find out. Through a chance meeting with a woman at the Martyrs Memorial in Algiers, a monument to those who died in the war of independence, she gains access to a variety of women who lived through the conflict.

The first woman Beatrice meets was one of the mujahidates who fought alongside the men. She, however, does not mince her words about the so-called 'heroes of the revolution'. She talks about how the racism of the French colonial masters radicalised her and others when they were just young.

It wasn't until after her father was arrested and tortured by the French, however, that she joined the resistance – just as the army was coming to pick her up.

Yet she quickly discovered the resistance wasn't much better than the French, especially when it came to women.

All revolutionaries are not equal

The first thing they wanted her to do upon joining was submit to a virginity test, which she refused. Women were still being relegated to serving the men and doing menial chores. The men were intent on consolidating their power, rewriting history in an attempt to negate the crucial role women had played in the resistance. When they killed one of her friends, she decided she had had enough and fled.

Following Beatrice's pilgrimage through Algeria, we're introduced to a French women who stayed in Algeria even after the war as it was her home – and one last resistance fighter. This last woman's story is the hardest to read. She was injured in an exchange of fire with French soldiers and is provided with treatment, only to be subsequently tortured for information. She is finally saved by a soldier who, disgusted with the situation, intervenes and manages to convince a doctor to admit her to hospital.

Normally a graphic novel isn't the place you go for a history lesson or enlightened thinking. However, in this case author Meralli and artist Deloupy have given us both. First, they present a balanced view of the conflict from the point of view of the women who survived it. They have no problems talking about the atrocities that were committed by both sides, during what is still considered the one of the most vicious revolutionary wars of the 20th century.

Stark imagery by Deloupy

As befits the medium, they've also used a combination of words and imagery to tell the story. At times they let the pictures tell the story on their own. This is where Deloupy's skills as an artist come to the fore. The images are stark and remarkable. We see the desperation, the hatred, the pain and the humanity these women experienced in the illustrated panels.

Some of the scenes depicted are quite graphic, with the potential to upset the more sensitive reader. However, this was not a pretty time in history and the choice to show it warts and all is valid. There is nothing gratuitous about this book, but it can be shocking in places.

One thing the authors are also very careful about is not presenting the women as victims passively accepting their fates. These are all individuals who were acting from conviction and hoping for a better world. For far too many, the revolution was more about gaining power than freeing people. They make it clear that these women held onto their ideals far longer than the men.

Algeriennes by Swann Meralli and Deloupy may upset a few people: it is not black and white in either its condemnation of one side, or in labelling villains, but it is probably one of the more accurate depictions of the war in Algeria you're liable to read or see in a long time.

While definitely not a work for a younger audience, it remains a brilliant example of how a graphic novel can sometimes be even more effective in telling a story than conventional prose narrative.

Richard Marcus

© Qantara.de 2021

Swann Meralli is the author of "L’Homme", with Ulric Stahl; "Fermons les yeux", with Laura Deo; and the series "Le petit livre qui dit", with Carole Crouzet. Illustrator Deloupy published the award-winning "Love story à l’iranienne", with Jane Deuxard, and "Pour la peau", with Sandrine Saint-Marc.