Politically motivated provocation

Ms. Akyol, what is it like working as a journalist in Istanbul at the moment?

Cigdem Akyol: At the risk of no-one believing me, I haven′t actually had any problems with the Turkish government. Ankara has always issued me with a press card, even if it has sometimes taken a while. I know other German journalists who waited a long time before they were accredited.

It's important to remember – and it's the reality – that Erdogan was elected democratically. Elections were partially not free and certainly not fair, but the man isn't a dictator. That means it's incredibly important not to be led by populist moods and remain factually oriented and cover the topic in a fair way. Of course it's not always easy, given the political situation – journalists are people after all. But one must also take into account the past positive aspects of Erdogan when reporting in order to explain his strength and determination today.

What positive aspects are you thinking of?

Akyol: At one point, he was actually a reformer. Among other things, he expanded women's rights and, for a time, freedom of the press. He led Turkey to the door of the EU and created a middle-class that did not exist before. Thanks to Erdogan, the social systems were improved. These aspects, of course, are things that have contributed hugely to his success. Under Erdogan, there was an economic boom which lasted years, the like of which Turkey had never seen before. But these aspects get ignored because they don't fit into the world picture that many, including the German-language press, have of Erdogan. Instead, everyone agrees he is a born tyrant.

But what remains of Erdogan the reformer?

Akyol: Not much, to be honest. Those claiming that Erdogan is still on a democratic path or that he's still interested in democratic reform is not living in the same Turkey as I do. The Turkey I live in is a land where people are afraid they will have their passports taken away, be put in jail or lose their jobs because they are critical of the government.

Under President Erdogan, not only was the German-Turkish correspondent of "Die Welt" Deniz Yucel taken into custody, but dozens of Turkish journalists critical of the regime are also sitting behind bars. How did it come to this?

Akyol: Relations between Erdogan and the press were never good. Above all, the Kemalist press, that was once very strong, really gave it to him. He now is taking his revenge. When he was mayor of Istanbul from 1994 to 1998, Erdogan complained that, no matter what he said, the Kemalist press always used it against him. They made fun of him and his impoverished background. They also made fun of his wife and daughter because they wore the hijab. Actually, there was no fair reporting. And while Erdogan himself never valued free word, he had to endure it. But since the failed coup attempt, he has carried out a huge cleansing wave, aimed at everyone who doesn't share his opinion.

As campaign appearances by Turkish ministers were cancelled in Germany, Erdogan spoke of "Nazi practices". Were the Nazi comparisons, in your opinion, serious or just a bit for attention?

Akyol: His absurd accusations are part of an electoral campaign. The inner unrest relating to the German-Turkish relationship, which is currently increasing in Germany, plays into Erdogan′s hands. He is fishing on the right for his presidential system and he needs the voices of the nationalists – that is why he is playing the nationalist tune once again. The more German politicians and the public react to it, the more he benefits. And that's why he's so hot on it at the moment. One shouldn't actually fall for this scam. My tip: stay objective and polite, yet continue to point the finger.

What issues, in your opinion, beg the most criticism up at the moment?

Akyol: The dismantling of whatever's left of democracy in Turkey. Berlin and Europe must be very clear that no more opposition politicians are to be imprisoned, that the few free, critical journalists in Turkey should not have to fear for their lives, that the rule of law is no longer eluded and that the balance of power is preserved.

What is the situation like for those critical of the government and those active in the cultural scene in Turkey?

Akyol: Criticism is moving underground. There are still people who demonstrate on the street for a "No" vote at the constitutional referendum, but they are usually arrested.

A major topic for those involved in culture and for intellectuals is the question "how can I leave this country?" Are there grants? What country is an option? At the moment, there is no hope for improvement as far as democratic developments in Turkey are concerned.

Interview conducted by Laura Doing

© Deutsche Welle 2017

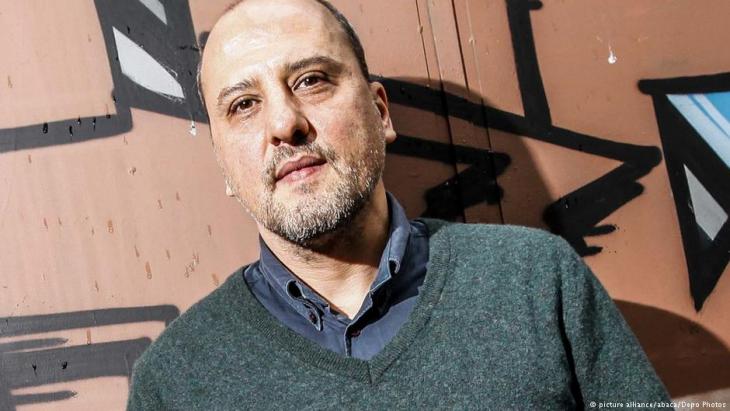

Cigdem Akyol lives in Istanbul and works as a correspondent for the Austrian news agency APA. She was born in Germany and is of Turkish-Kurdish heritage. Her unauthorised biography on Erdogan was published in 2016.