Electioneering in the Federal Republic: Courting the immigrant vote

When Cem Ozdemir became the first Turkish-German member of the German parliament, the Bundestag, in 1994, his office soon received many angry calls. "What's going on, what's the Turk doing up there?" an enraged voter complained about the fact that Ozdemir – then parliamentary secretary – was sitting on the podium in the centre of the Bundestag. "Since when is a Turk allowed to sit up there?"

Today, Ozdemir is a fixture in German politics as the leader of the Green party and a main face of their election campaign. He is also one of eleven Germans with Turkish roots in the national parliament.

The fact that Germany is an increasingly diverse country is starting to show in its electorate and political personnel. One in ten eligible voters has a migrant background, meaning that they or their parents were not born as German citizens. A total of 37 out of 631 Bundestag representatives migrated to Germany or are the children of migrants.

German parties and media are starting to devote more attention to the voting behaviour of Germans whose parents or great-great-grandparents weren't born in Germany, in particular the two largest migrant groups: so called late repatriates ("Spataussiedler") – ethnic Germans from largely former Soviet countries – and Turkish-Germans.

There are 3.1 million repatriates living in Germany, according to the 2016 micro-census. The Federal Statistics Office (Destatis) estimates there are 730,000 Germans with Turkish roots eligible to vote in the federal election on 24 September.

Preference for the political left

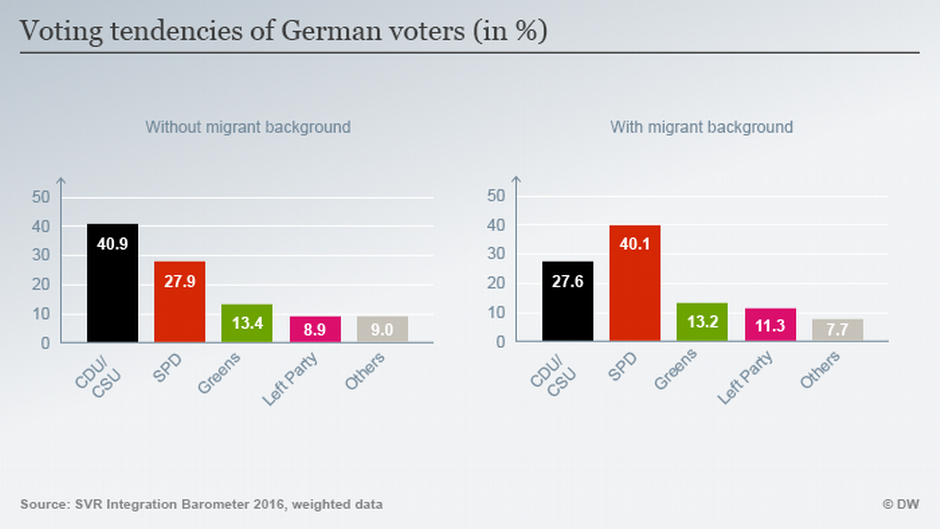

According to political scientist Andreas Wust, voters with a migrant background tend to prefer parties from the political left. Such parties tend to be more open towards people with a migrant background and their concerns. While this also applies to Germany, a closer look at different migrant groups reveals that this tendency is certainly not true for all Germans with a migrant background.

According to Dennis Spies, a researcher on voter behaviour of Germans with foreign roots, migrant voters are not a monolith political force. "The group [of Germans with a migrant background] is growing, but heavily split politically," says Spies.

"There is no one single type of migrant voter. Why should somebody who came to Germany from Ukraine 20 years ago have the same political preferences as somebody who moved here from southern Turkey? Or somebody who came here from Italy in the 1950s?″

Yet certain trends are visible among certain groups. Late repatriates tend to vote right-wing, Turkish-Germans predominantly cast their ballots for the centre-left.The late repatriate vote

German migration authorities have special rules for ethnic Germans from former Soviet states that make it easier for them to gain German citizenship. Because former Chancellor Helmut Kohl pushed for this after the fall of the Soviet empire, Russian-Germans, Kazach-Germans and the like were long seen as loyal voters of his Christian Democrat party (CDU). But things changed when the CDU's Chancellor Angela Merkel decided to let over a million refugees into the country.

"Jealousy does play a part here," admits political scientist Spies.

The right-wing populist Alternative for Germany (AfD) has been targeting Russian-Germans with campaign materials in Russian. This approach helped the anti-migrant, anti-Islam party score big in districts with a strong Russian-German population in the last few state elections.The CDU is now attempting to win that vote back, promising higher pensions to repatriates.

The Turkish-German vote

Turkish-German voters have long had strong ties to the Social Democrats (SPD), a result of the fact that most Turks came to Germany as "guest workers" during the economic boom in the 1960s. The SPD has historically been the party of German workers and was among the first to push for dual citizenship and the rights of migrants. According to a study published by the expert council on integration and migration, 70 percent of all Turks support the SPD – that number is twice as high as in the general electorate. Support for the Greens is also significantly higher among Turkish-Germans compared to the overall electorate.

The growing tension between much of the German political mainstream and Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdogan, however, has put the usual predictions about the German-Turkish vote in question. Erdogan called on Turkish-Germans to boycott the CDU, the SPD and the Greens, whose leading candidates have all criticised his growing autocratic tendencies.

In response to Erdogan's statement, many prominent politicians asked Turkish-Germans to turn out to vote. "Don't let Erdogan push you to the borders of our [German] society," said Aydan Ozoguz (SPD), the federal commissioner for integration and migration.

The voter turnout of Germans with foreign roots tends to be much lower than among the overall population ("up to twenty percentage points," said Ozoguz).

"Your President Erdogan"

Just like Ozdemir over twenty years ago, German migrants and descendants of migrants who make it into the highest ranks of German politics also often still face racist sentiments and the notion that they are not "truly German".

Iran-born politician Omid Nouripour of the Greens said he regularly received hate mail telling him things like "You sh*t Arab, go back to Turkey." AfD politician Alexander Gauland caused an outrage when he said Hamburg-born Ozoguz "should be disposed of in Anatolia."

"I am German and I only have German citizenship! When will you finally get that into your head?!″ Ozcan Mutlu recently had to tell a fellow Bundestag representative during a debate on dual citizenship, after the latter referred to the Turkish head of state as "your president Erdogan."

Andrea Grunau

© Deutsche Welle 2017