Friendship across the divide

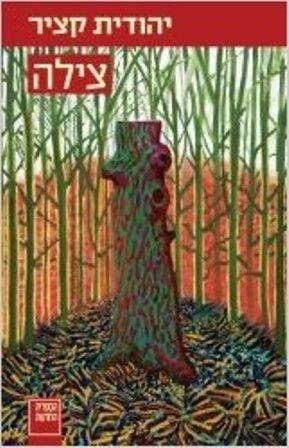

Your new novel, which is very successful in Israel, is called "Tzila". Who was this woman?

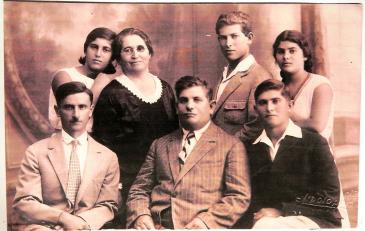

Judith Katzir: Tzila Margolin was a strong woman who never attended school, but nevertheless published feminist articles. She nearly lost her life in a pogrom, in which she lost one eye.

Tzila was also a mother of five and kept a secret. What was this secret?

Katzir: She shared her life with two men. Her relationship with her husband, Eliezer, was burdened by her intellectual superiority and her wider horizons. At the age of 37, she met Chanan, who was nine years younger than she. He was literarily gifted, spoke nine languages and was a committed vegetarian. He lived together with Tzila's family for 25 years, until Eliezer passed away.

The affair began when Eliezer found work in Gaza.

Katzir: In 1919, Eliezer moved to Gaza in order to start operating an abandoned flour mill, which had belonged to a German who had fled during the First World War. Eliezer renovated the mill – the only one left in the destroyed town – which allowed him to feed his family.

My great-grandmother Tzila could not be without Chanan, so she brought him to Gaza to work as a private teacher to her children. It was only when other Jewish families moved in that the first Hebrew school – the "Samson" School – was opened and a professional teacher arrived.

What was life like for the few Jews living in Gaza?

Katzir: My family, the Margolins, was the first to move to Gaza after the war, in the autumn of 1919. They rented a five-room apartment with an inner courtyard, where all Jewish visitors would spend the night before the first guesthouse in Gaza opened. Encouraged by the British government and the Zionist Council, other Zionist families settled in Gaza – a doctor, a watchmaker, a baker, a carpenter. Then, in the autumn of 1920, the Zionist leadership sent the first Hebrew teacher, a new immigrant from Russia.

How important was your family for this tiny community?

Katzir: Very important. Tzila was very active in the community, and her four children made up the majority in the class of seven pupils. Very soon however, she became dissatisfied with this school. She criticised the huge age difference among the children, some of whom could barely speak Hebrew. To begin with, classes were held outdoors and later in a shabby room. When Tzila moved back to Tel Aviv, the teacher resigned in 1921. As a result, the Zionist Council refused to send a replacement for a school with less than twelve children.

Eliezer then accused Tzila of destroying the Jewish community in Gaza: it was feared that the other families would leave if their children did not receive any education. Tzila gave in. She put the common good above her private life and returned to Gaza in the autumn of 1922 with her five children, but without Chanan. A new teacher soon arrived, and the Hebrew school was reopened.

Describe the relations between the Arabs and the Zionist Jews in Gaza?

Katzir: In the early years, they were very good. Eliezer, who was head of the community and represented it in the local court, was called Abu Jusuf by the Arabs. He was a close friend of the former mayor Said al-Shawa.

Eliezer's eldest son, Josef, recalled that the family maintained close ties with the Arab mill workers. When one of them married, Josef spent a whole week at the groom's house and celebrated according to Arab tradition with singing, dancing and story-telling.

The Jews lived right next door to the Arabs, and their children grew up together. The five children and my great-grandmother all spoke fluent Arabic in addition to Yiddish, which they spoke at home, and Hebrew, the language of education.

Several Arab neighbours saved Jewish families during the civil war of 1921 by secretly providing them with water against the orders of the Arab leadership.

But in the riots that took place in August 1929, even these Arab were powerless. Why?

Katzir: Tzila and the children left Gaza in 1925. At the time of the attack, Eliezer was still living in Gaza, and two of his daughters were visiting for the summer holidays.

When news of the massacre of Jews in Hebron arrived, the 44 Jews in Gaza locked themselves in the only Jewish guesthouse, where they spent the night. When most of the British soldiers fled the next morning, the Arab mob broke in. However, the Jews poured acid over the attackers and pushed them back.

When al-Shawa, the former Arab mayor, arrived, he helped the British soldiers evacuate the besieged Jews to a train that had been provided in order to take them to Tel Aviv. They were evacuated under a barrage of stones being thrown by rioting Arab teenagers.

Did the friendship between your family and their friends in Gaza last after Tzila's death in 1967?

Katzir: Yes. Until the first Intifada of 1987, they visited each other in Gaza and Israel.

These days, my two daughters and I repeatedly have to shelter from the rockets fired from Gaza on the staircase.

The increasing violence by Jewish right-extremists and the intolerance shown towards those who think differently about the war really shocks me. I used to be active in the "Geneva Initiative", in which Israelis and Palestinians negotiated a common model for a peace deal. Now, in view of the great despair, I hope there will soon be an end to the bloodshed and a diplomatic solution to this conflict. Then, I hope, I will one day be able to visit the descendants of my great-grandparents' neighbours in Gaza.

Interview conducted by Igal Avidan

© Qantara.de 2014

Editor: Aingeal Flanagan/Qantara.de