''The Rebellion's Perseverance Surprises Me''

At the moment, we're hearing a lot about "the" opposition to the Syrian regime. Who exactly is behind the opposition?

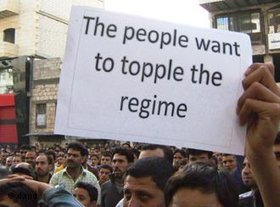

Rafik Schami: The uprising developed out of the mass of people who are fed up with the status quo. Who are the members of the opposition groups? Everyone taking part in the demonstrations; everyone who supports the demonstrators in their demands for freedom and democracy. Many parties that have thus far remained quiet are now also joining in. Some are even claiming that they were involved from the start.

The Muslim Brotherhood, small Communist parties, young academics … what unites the many different groups that make up the Syrian opposition?

Schami: What is holding these groups together at the moment is the goal of toppling Assad. But that does not make for a strong bond; it's merely strategic. It is only a temporary "front". I think that we will soon see a division. As soon as the regime begins to weaken, each group will have to present its own model for the future; say what kind of state they want to see. I hope that this debate will take place peacefully. There is always the danger that the situation could culminate in a civil war.

Do you think there are any differences between the Syrian opposition and those in Tunisia or Egypt?

Schami: I think the difference is the harshness with which the government has reacted, taking extremely brutal action against the protesters. Even friends of the regime found this shocking. However, what is even more surprising is the perseverance of the rebellion.

I could never have imagined that an uprising would last into a fourth month, with over 2,000 dead and more than 25,000 people arrested. And still they go out onto the streets day after day – no longer just on Fridays, but every day. That's what makes them different from the short-lived, successful Tunisian protests and the somewhat longer demonstrations in Egypt, which – despite all the excesses of the intelligence service there – went off more or less peacefully.

What makes it so difficult for the Syrian opposition to make any headway against Bashar Al-Assad?

Schami: The durability of his regime. There are 15 intelligence agencies working systematically and extremely cleverly. Anyone who underestimates the Syrian intelligence corps is either very naïve or hasn't done much reading. Besides, the regime is made up not only of Alawites, but also includes all the other religious denominations. The Alawites represent the state's elite, the leading figures, but Sunnis, Christians, Druze and Cherkessians also work hand in hand with the regime.

The long years of rule, the many diligent intelligence services that have infiltrated all parts of society, the approval of the regime by the various political groupings – which have either been paid off or bribed – and the solidarity of mid- to high-income earners have weakened the opposition. Together with the iron fist wielded against anyone who gets out of line – and mercilessness toward expatriates; we academics and intellectuals abroad number over 500,000 – that's a huge number of troublemakers who have been kept out of the country.

Speaking of troublemakers, do you count yourself as a member of the Syrian opposition?

Schami: I have been in opposition to this regime from the outset, because I realised right at the start that it represented a return to clan rule. We no longer have a republic. A republic cannot be inherited, and a stupid parliament that unanimously votes for hereditary rule is to my mind not a parliament at all.

In the 1950s we were a very defiant, wonderful republic – I had the privilege of experiencing that when I was a young man. There were genuine elections back then, real newspapers; we didn't have a single political prisoner, we lived free and had no fear of the government. We dared to badmouth anyone – that was the Syria of my childhood and youth.

And suddenly a regime comes to power that robs us of all freedoms, that sends me into exile – that's why I've been a member of the opposition from the start. I don't belong to any group or party. I am in favour of a secular state, in other words: the separation of church and state. And I am for diversity and freedom for those who think differently.

That means you support the opposition in Syria?

Schami: I support them, as all intellectuals must, namely by driving forward the discussion. What do you want to see happen afterwards? Don't tell me that you want to bring down Assad! What kind of state are you striving for? What about the rights of women? What about the freedom to bring up children without a prescribed ideology? What about the rule of the clan? What I mean to say is: the intellectuals abroad must advance the discussion and caution against sectarianism and vengefulness.

It is not the purpose of a revolution to single out a certain group as scapegoat. A revolution should liberate us and give us the courage to reach out and take each other's hand. That is my plea for a future for Syria.

And how should Germany support the Syrian opposition?

Schami: We should show ourselves to be worthy of our freedom and our democracy, for which we had to fight so hard here in Germany. They represent an obligation for us. Freedom means not only being able to choose where we want to go on holiday, but also sympathising with others. We do so by speaking out clearly and boldly for democracy and freedom in Syria and admonishing violence against demonstrators.

But the language being used in Berlin is instead full of "ifs and buts". It makes the German politicians seem small-minded, always standing in the second row. That bothers me a bit, because I've been living here for 40 years and I love the country that gave me a homeland, that gave me a language. I very much regret that on the one hand, we constitute a major world power in terms of industry and on the other, we still want to play the role of a small child when it comes to politics.

It won't do to wait until Mrs Clinton makes a decision on our behalf. Mrs Clinton is so lax toward Syria that the Syrians are laughing at her.

Rafik Schami was born in 1946 in Damascus and has lived in Germany since 1971. He is one of the most important living German-speaking authors. His works, which have won numerous awards, have been translated into 25 languages.

Interview conducted by Anne Allmeling

© Deutsche Welle 2011

Translated from the German by Jennifer Taylor

Editor: Aingeal Flanagan/Qantara.de