"Politics needs a new language"

The academic and Turkish literature expert Franz Taeschner once put forward the theory that modern Turkish literature was European literature written in Turkish. But you say a writer should stay connected with the soil on which he lives. How does that fit together?

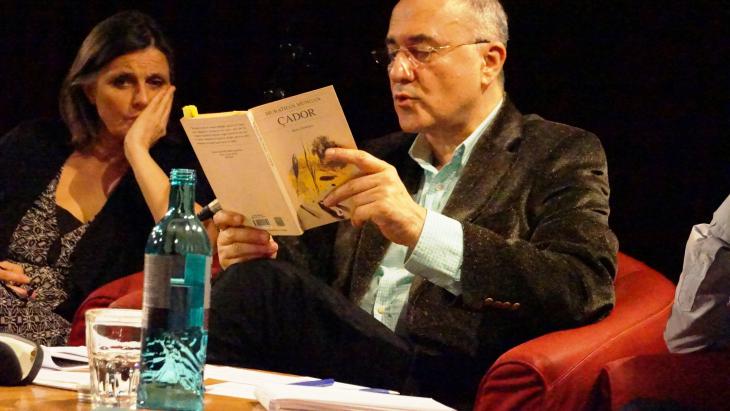

Murathan Mungan: I can't say anything about this theory of Taeschner's, because I don't know in what context he said it and exactly what he meant.

The sentence you quote is from my book "Studio Shots"*. It's a metaphor. What I meant by that was that every writer comes into an inheritance of the geography, culture and history of the place in which he lives. That is not to say that he will only be understood by the society of this place, but rather that he should direct his words to the whole world from this soil. It also describes the way in which we should connect with people in other parts of the world.

In my book "The novel of the poet", I give another example involving soil. We all make clay pots out of the earth, but it must be done so that you can use them all over the world – in Canada, Scandinavia, Japan. At the same time, this example expresses my understanding of art and my understanding of the relationship that a writer or a poet should build with his own personal memories and those of his society.

You are well known for your very precise and considered use of language. In relation to the Gezi movement, it is often said that the new generation in Turkey speaks a language that the people in power don't understand. What power does language have to help change social conditions?

Mungan: Language is in itself a philosophical subject, and when we talk about language, we have to distinguish between street language, everyday language, the language of discourse, your own native language and a foreign language. The language in which I write is a literary language.

Sentences that are written down also contain many sentences that are not written down. This means that they contain the echo of many sentences that are not written down. A writer should enrich his country's language. He has to find his own language, to differentiate him from everyone else. I would like to challenge the language, find new possibilities and new connotations, and write in a language that binds the reader to the book. At the same time, it's a challenge to make a literary language out of everyday language.

There has been a difference between the language of young people and that of the government for a long time. We see that all verbal arguments reach a dead end, and that politics needs a new language. In this context, one also has to consider the relationship between language and ideology, and at the same time, the younger generation has to question its knowledge of language. The relationship between language and thought is important too. It's a dialectical process: a new language brings new thoughts with it. The problem is that at the moment, we have languages that are cut off from each other, that don't understand each other.

In the assessments of the local elections that have taken place in Turkey, the main focus has been on the row between the AKP and the opposition party, the CHP, but there have been other developments too: in many provinces, there are now women mayors, the BDP/HDP has gained a lot of mayoral seats, and LGBT activists have been elected to city councils. You've always been a strong supporter of the Kurdish movement and the gay movement. What's your assessment of these developments?

Mungan: The picture really speaks for itself. In Turkey right now, we're seeing a change in the language and the ways of politics. It's interesting to see in how many provinces the BDP or the HDP have won local elections. On the other hand, I recently read in the news that somebody in Bingol declared that having a female mayor went against our customs. These are all different aspects of the same picture. It's important that we start talking about democracy again now, about new ways to find our identity and win our case. It's part of a process we're going through.

You say you don't like the word optimistic, but in general you always seem optimistic when it comes to developments in Turkey. At the same time, you once said that you can do anything in Turkey, but you're not allowed to disgrace yourself. Do you still feel as positive following the accusations of corruption against representatives of the AKP, which so far have not been followed up?

Mungan: First of all, I have to say that, as far as my own life goes, I'm no butterfly happily fluttering around. But I try not to think in terms of categories like optimistic, pessimistic, happy, unhappy, hopeful, hopeless; I try to find an objective yardstick, to see the entire picture, the whole process.

There's a quote from a French thinker, whose name I can't remember, who said: my experiences make me pessimistic; my will makes me optimistic. That's the best way to describe my attitude. We have to find new paths of resistance. And I think the greatest resistance is to do what you do best. The system can take everything from me, but my ability and my belief in what I do best will always remain.

In your book "Chador" you depict a horrific scenario of a country ruled by Islamists. A lot of people thought the AKP would gradually turn Turkey into an Islamist state. After so many years of the AKP in government, is this fear still justified?

Mungan: It wouldn't be right to reduce "Chador" to a particular party or a country. What I wanted to show was what can happen when Islam is politicised, when secular thinking is extinguished and laicism is abolished. I wrote the book between 2001 and 2003, and it carries traces of what I was reading on the topic at that time, as well as daily life in Iran, Afghanistan or Saudi Arabia. It's a fictitious story that I came up with to explore this question. But if you just think about what could potentially happen in Syria right now, it's very frightening.

My book is about being seen and not seen. When you start to veil women in a society, they are not all that's veiled. At the same time, you draw a veil over reality and that in turn brings with it a loss of reality at the perceptual level.

Interview conducted by Ceyda Nurtsch

© Qantara.de 2014

Translated from the German by Ruth Martin

* None of Mungan's works have as yet been translated into English. These titles are not, therefore, the titles of published, official translations of his works – ed.