The naked brutality of war

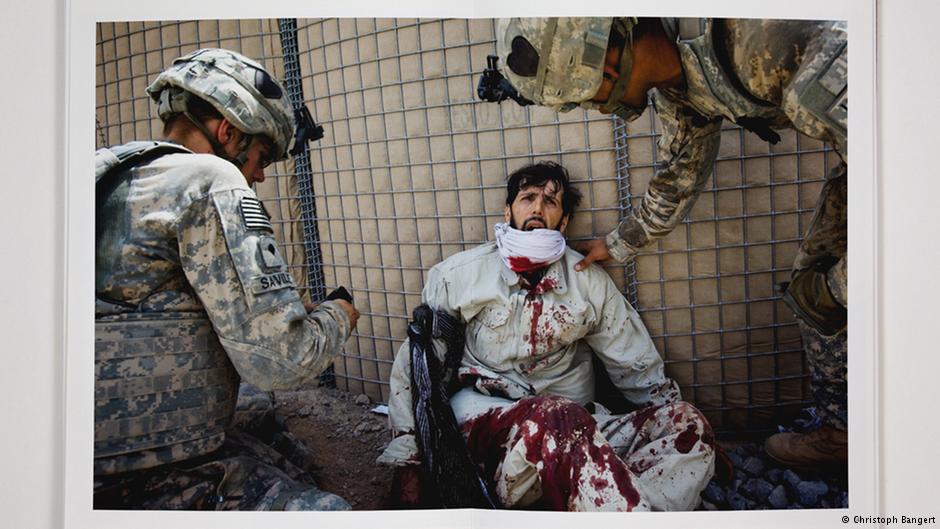

Mr Bangert, those who look through your book "War Porn" get an entirely unfiltered perspective on war: a beheaded man's body eaten at by dogs and ditched in a dump; a baby left alone in a basket after a house was stormed; a naked and battered body on a blood-soaked sheet. Do photos of war have to be so brutal?

Christoph Bangert: The images have to be as brutal as the war itself. A war is nothing sacred, nothing extraordinary. People have been fighting wars throughout human history. That has to be documented just like anything else. Then it's up to us what we make of it – or don't, as the case may be.

When I look at your pictures, I have the impulse to look away. As a photographer, you have to look at what is happening on the ground. How difficult is this for you?

Bangert: It is very hard. As a photographer, you have to overcome your inclinations in order to work and be professional in such extreme situations. But this is very important. I travel to these regions because I have been commissioned to capture these images. And I have to publish them. Sadly, the most disturbing pictures are sometimes not published, which is how this book came about.

Many of the pictures in your book have not been published elsewhere because they were deemed too shocking. We too are only going to show the "more harmless" images. Can you understand this self-censorship, this impulse to protect oneself from horror?

Bangert: That is a totally natural reaction. Essentially, self-censorship takes place in three stages. First, the photographer does it. There are a lot of pictures that I don't send to the editorial department. Next, editors decide what they do and do not want to show. And the third stage, which is actually the most interesting one, is the one that we all go through. As observers, we often don't want to see the images. We avoid them. We cannot overcome our inclinations. As such, this book is not only a critique of the media and of the self, it is also a criticism of us all as observers. We all have a responsibility to actively seek out such images and to look at them – even if it's very difficult.

Why do we have to look at these pictures?

Bangert: We have to look at these things because they have really happened. We recollect still images rather than sounds, documents or videos. So, photography creates memories in people. When we leave out the horror and the terror from war reporting, then people don't remember these aspects. That is the danger. The context in which the pictures are published is just as important. It doesn't make sense to publish the pictures on the front page of a tabloid just to shock people and boost circulation. You have to go beyond the shock everybody experiences.

What does that mean?

Bangert: We often see images showing the drama of war: rolling tanks or young men with Kalashnikovs. We have seen these things a thousand times. But it is relatively easy to look at these pictures. We hardly ever see the real horror of war. That is ultimately crazy. It is our job to find a context, a way to show these pictures. I have tried to do so with my book.

But don't we become inured to such images when we see ever more shocking scenes?

Bangert: I don't think that we do become inured. These things are so terrible; they touch everybody. You can't get used to them. Think about the images of the liberation of Auschwitz. It is so extreme, so terrible. If we were to become inured to such images, we wouldn't be human anymore. We don't need to look at these pictures every day, but we should see them. But we don't do it because it is so difficult for us, because we are constantly censoring ourselves.

But aren't you just pandering to voyeuristic needs? Your book is entitled "War Porn" – inspired by soldiers and civilians in places like Afghanistan who sometimes swap pictures of atrocities as one would porn magazines or soccer cards.

Bangert: These pictures are to a certain extent always dehumanising. But the event – that which really happened – is, of course, the terrible thing. That's what's unbearable; not the image. We're only creating images of this reality. The events themselves are always far worse than what you can show in an image. But that doesn't mean that we don't have to publish these images.

You can always call it pornographic or voyeuristic. I have often experienced, though, that this argument is used as an excuse not to have to look at the photos. But there is no excuse not to acknowledge and view these photos.

The images are often photographically aesthetic. Beautiful pictures of war - isn't that absurd?

Bangert: War is absurd – these strange things that happen in these situations and make no sense at all. War is horrific. I can't take poor pictures just because the issue is so serious. But that doesn't mean that we think what's happening there is good. My job is to take good pictures because no one looks at bad pictures. And I want people to really look at these images.

Does your work also help the victims, the people you take pictures of?

Bangert: I don't help anyone. I just record what I see and experience, as honestly and truthfully as I can – even though it is never impartial.

Have the things you have seen and experienced sometimes made you cry?

Bangert: Not me, but some of my colleagues. Emotionally, the most difficult moment for me as a photographer comes later. On the ground, you're very concentrated. Everything happens very fast, and you work intuitively to try to take a technically good picture. You don't have time to reflect on it. It's more difficult later when you're looking at the pictures and you then really take in what you have seen.

These images are not only on camera and on the hard drive, but also in my head. That's a struggle. But it is a mercy, too: many people who have been in extreme situations – soldiers, but also civilians in war zones – have nothing when they come back. It is very difficult to put into words what you have experienced. Having the images is my great fortune. When I have to tell my family or my friends what I have experienced, I don't have to talk much. I just show them the pictures.

Interview conducted by Monika Griebeler

© Deutsche Welle 2014

Editor: Greg Wiser/DW and Aingeal Flanagan/Qantara.de

Christoph Bangert (b. 1978) is a photographer and journalist. He studied photography in Dortmund and New York. Bangert now works in war and crisis zones including Afghanistan, Darfur, Pakistan, Nigeria and the Palestinian territories. He documented the war in Iraq for the "New York Times" and has won multiple awards for his photography.