Tarred with the same brush

A climate of fear pervades Germany and Europe. The fear of Islamist terrorism and the fear of Islam itself. In a Pew survey conducted in 2016, half of the respondents in eight out of ten European Union countries expressed fear that the influx of Muslim refugees could increase the risk of terrorist attacks. The greatest anxiety was felt in Hungary at 76 percent, followed by Poland (71 percent) and then Germany and the Netherlands (both 61 percent).

Is this fear of Islam, of Islamism and Islamist terrorism, utterly groundless? No, it is not entirely unfounded. It is socially construed and tied to the anti-Muslim racism that is entrenched in society and which fails to distinguish between Islam and Islamism.

"Over half the population perceives Islam as a threat and an even higher proportion is of the opinion that Islam is not compatible with life in the Western world." These are the findings made in the "Religion Monitor 2015 – Special Evaluation of Islam" published by the Bertelsmann Foundation. According to this study, 24 percent of people in Germany agreed "fully and completely" or "rather strongly" with the statement "Muslims should be prohibited from immigrating into Germany".

Distorted perception

A similar perception of Muslims and Islam as a threat and alien to Europe had already been established by Andreas Zick, Beate Kupper and Andreas Hovermann in their 2011 study "Devaluing the Others". A total of 17 percent of the German respondents and an average of 22 percent of the Europeans surveyed agreed with the statement: "The majority of Muslims believe that Islamist terrorism justified."

In fact, however, Islamist terrorism represents a much smaller threat to public safety than is suggested by political rhetoric and media reports. Looking at the phenomenon of "terrorism" from a sober distance, we can verify two things:

- Other forms of government and non-government violence statistically harbour higher risk potential for both domestic and international security; in other words, an individual is more likely to be a victim of war or murder than of a terrorist attack.

- The history of modern terrorism includes not only Islamist groupings but to a much greater extent national or social-revolutionary terrorist movements; Islamist terrorism is thus by no means a singular phenomenon or one marked by exceptional brutality.

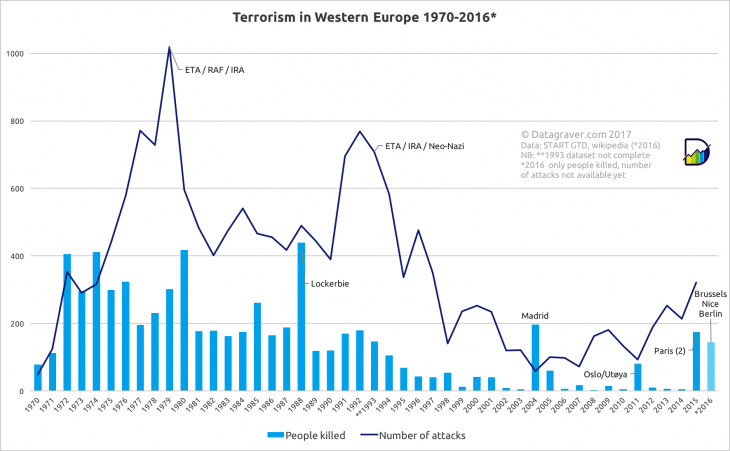

Actual threat of Islamist terrorism in a historical context: in Western Europe, 5,819 people lost their lives between 1970 and 2000 in attacks perpetrated by national or social-revolutionary terrorist groups such as the IRA, ETA and RAF. During the same period, Islamist terrorism claimed 61 lives. And between 2001 and 2016, 225 people in Europe fell victim to primarily right-wing terrorism and 554 were killed by Islamist terrorism

The real figures: According to the "Global Terrorism Index", 32,685 people were killed worldwide in terrorist attacks in 2015. That same year, 437,000 people fell victim to non-terrorist violence such as war or murder.

Even in regions that suffer most under Islamist terrorism, the risk of being harmed by non-terrorist violence is significantly higher: IS/Daesh, Boko Haram and Al-Shabaab killed more than 13,000 people in Iraq, Syria, Nigeria and Somalia in 2014. But in Iraq alone, at least 405,000 civilians were killed through direct or indirect hostilities between 2001 and 2003 – the equivalent of 45,000 victims per year.

And looking at Europe in the period up to 1970 also puts the threat of Islamist terrorism into perspective. In Western Europe, 5,819 people lost their lives between 1970 and 2000 in attacks perpetrated by national or social-revolutionary terrorist groups such as the IRA, ETA and RAF.

During the same period, Islamist terrorism claimed 61 lives. And between 2001 and 2016, 225 people in Europe fell victim to primarily right-wing terrorism and 554 were killed by Islamist terrorism. (Fig. Datagraver)

The danger of Islamism is overestimated

Just to prevent any misunderstandings: the aim here is not to trivialise the dangers of Islamist terrorism. Nevertheless, an analysis of the terrorist threat shows that the danger of Islamism tends to be overestimated. Or, to repeat the words of risk researcher Ortwin Renn: People in Europe have a higher chance of dying of mushroom poisoning than of being the victim of a terrorist attack. And yet the fear of Islamist terrorism is almost omnipresent and serves to guide political action. Why?

We humans try to understand the social world around us by means of "mindset" – i.e., with the help of assumptions about the behaviour and intentions of others. These mindsets are shaped by our own experiences as well as by collective memories or media coverage and they help us to cope with the flood of information confronting us daily, reducing it to a manageable scale.

With the help of these assumptions (mindsets), we develop an image of other social actors that allows us to make statements about their (expected) behaviour and intentions. This image then acts as a lens that focuses only on limited information – and serves as a blueprint for interpreting that information.[embed:render:embedded:node:14410]

The information available to the public about Muslim refugees from Syria is ambivalent; only with the corresponding image can we attempt to classify and assess what we believe beyond the available information, but always as a function of the image we already have.

Reliance on established preconceptions

The negative assumptions that have taken root in Germany and Europe about Islam and Muslims as dangerous and alien generate mindsets within whose bounds individuals attempt to make sense of new and inaccurate information they receive about refugees, Muslims fleeing their countries and the terrorist threat they represent.

We can see how mindsets work based on an experience Guido Menzio, an Italian mathematics professor, had on a domestic flight in the USA: due to his appearance (dusky complexion and black hair), he was regarded with suspicion by the woman sitting next to him on the plane and the fact that he was also apparently writing in Arabic characters (which were in fact mathematical formulas) was enough for the woman to sound the terrorism alarm in the aircraft.

The woman interpreted the scant information available to her – "man with a certain look writing unknown characters" – based on her mindset. This example shows how relying on established preconceptions can cause us to interpret inaccurate information as fact and then jump to conclusions.

Just as this woman saw the mathematician as a likely terrorist, we also identify refugees as terrorists, or we read non-specific news items about "threatening individuals" and immediately associate the threat with Islamist terrorism. Not because it's true but because our socially established preconceptions about Islam and Muslims suggest to us this interpretation of social reality. Muslims are not terrorists – we only construe them as such.

Andreas Bock

© Qantara.de 2017

Translated from the German by Jennifer Taylor

Prof. Dr. Andreas M. Bock is a professor of political science at Akkon University for Applied Sciences in Berlin and also holds a teaching post in international politics and conflict analysis at the University of Augsburg. His research focuses on terrorism, racism and political psychology.