Freedom under Threat

Friday, 30 March 2013: The large lecture hall in the science faculty at the El Manar campus university in Tunis is full to bursting. Some 200 university lecturers and academics from all over Tunisia and abroad have gathered here for the World Social Forum.

The only subject on the agenda is freedom for research and tuition in Tunisia. The academics are here to sound alarm bells: They, some of them active participants in the protests that toppled the old regime in early 2011, now perceive this hard-won freedom of speech and autonomy for Tunisian universities to be under threat.

Habib Mellakh, a professor of French literature at La Manouba University, is a member of the "Monitoring Centre for the Observance of Academic Freedoms" in Tunisia, an organization with close trade union associations.

The committee presented its most recent report in March. It claims that attacks on Tunisian universities by religious extremists are coordinated and not isolated incidents. At La Manouba University, for example, the perpetrators are known by name, says Habib Mellakh: "This is a deliberately orchestrated campaign against the autonomy of universities and against public freedoms," he says.

Mellakh goes on to say that the campaign is being waged with the tacit approval of the governing Ennahda party: "They regard the Salafists as their natural ally within the Islamist movement."

Islamist ideological onslaught

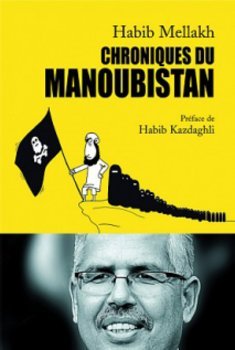

Habib Mellakh has just presented a new book in Tunisia. The almost 300-page book, published by the respected Tunisian publisher of academic literature CERES, is titled "Chronicles from Manoubistan". In it, Habib Mellakh describes in detailed and exemplary fashion the ideological onslaught being carried out for almost two years by Salafists and Islamists against academics and students at La Manouba University near Tunis.

Amel Grami, a professor of Arab language and intellectual history at La Manouba, was one of the first targeted by the Salafists in the autumn of 2011. The religious zealots condemned her as a "kaafira" (infidel) because she did not wear a veil when teaching and because she did not allow any fully-veiled students to attend her courses.

The Salafists accused her of, among other things, carrying out missionary work and used Stasi-style methods to discover what was being said during lessons given by the apparently "godless" professor. "I taught a seminar on comparative religious studies. The Salafists claimed I was trying to convert students to Christianity or Judaism," recalls Amel Grami. "They also asked my students what had been discussed during the seminar."

Attacks on cultural events, besiegement of lecture halls

The men in long, Wahhabi-style shirts, some of whom were not even enrolled at the university, demonstrated for the "human right" of female students to wear the full veil and the "cultural identity" bound up with this.

They attacked cultural events, such as the participation of students in the worldwide "Harlem shake" video dance craze. One of their declared goals was to impose separate areas for women in lecture halls and university restaurants. In some instances, male students were forcibly prevented from entering lecture theatres or canteens.

At La Manouba's faculty of philosophy, Salafists blocked entrances to lecture theatre buildings and seminar rooms for several weeks. University Dean Habib Kazdaghli, a history professor, was prevented from entering his office. Because police only made hesitant attempts to end the illegal sit-ins, many professors at the university went on strike. At times, all tuition at the faculty of philosophy had to be totally suspended for security reasons.

After university administrators banned certain individuals from entering the campus, on 6 March 2012 two fully-veiled female students stormed and trashed the Dean's office. But it wasn't the two students who were then hauled before a judge, it was the Dean himself, who was accused of hitting one of the two students.

Fundamentalists' accomplices

Habib Kazdaghli issued a robust denial of the accusation from the very outset. But it was no use. The Dean, who is officially still in post, has been on trial since 5 July 2012: A judgment has not yet been pronounced. Kazdaghli refers to the university's internal regulations set down in the autumn of 2011, which stipulate that teachers and students must be able to see each other: "The authorities responsible are not helping us to impose this rule," says Kazdaghli. "Instead, this makes them fundamentalists' accomplices."

La Manouba is not an isolated case: Radical Islamists are currently attempting to impose what they believe to be "the true Islam" at several universities in Tunisia. They even attained a partial victory at the university of Monastir: According to the report by the trade union-affiliated monitoring body, women there are now made to sit in a segregated area in the canteen.

Liberal and secular university lecturers suspect that campaigns such as these are intended to demoralise. They assume that the governing Ennahda party plans to curtail rights and freedom of speech at the country's universities in Tunisia's future constitution. Habib Kazdaghli also suspects that the Ennahda government is planning to appoint politically agreeable personnel to senior positions at Tunisian universities in the near future.

"The Islamist governing party knows that it does not have the universities under control. The police, journalists, the army – politically, the elites are not in line with the Islamists. That's why they have to keep up the pressure. And the Ennahda party is very adept at this," says Kazdaghli.

The apparently politically motivated trial against historian Habib Kazdaghli has triggered a worldwide wave of solidarity. Numerous academics at German universities have also appealed to the Tunisian government to guarantee the freedom of the universities as well as conditions that facilitate unimpeded academic tuition and research.

Habib Kazdaghli is frustrated because the perpetual provocations of the Salafists are robbing him of time – time that he needs to fulfil his duties as professor and Dean. "Of the 900,000 young people who are officially out of work in Tunisia, one in every three has a university degree," says Kazdaghli. "We should be doing all we can to improve education and job prospects for these students. Instead, we're wasting our valuable energy on useless disputes like this one."

The next court hearing in the trial against Habib Kazdaghli has been scheduled for 18 April 2013. Observers and lawyers expect the professor to be acquitted due to a lack of reliable evidence. But even if he is, the battle for freedom at Tunisia's universities is still far from won.

Martina Sabra

© Qantara.de 2013

Translated from the German by Nina Coon

Editor: Lewis Gropp/Qantara.de