Across snotgrean seas

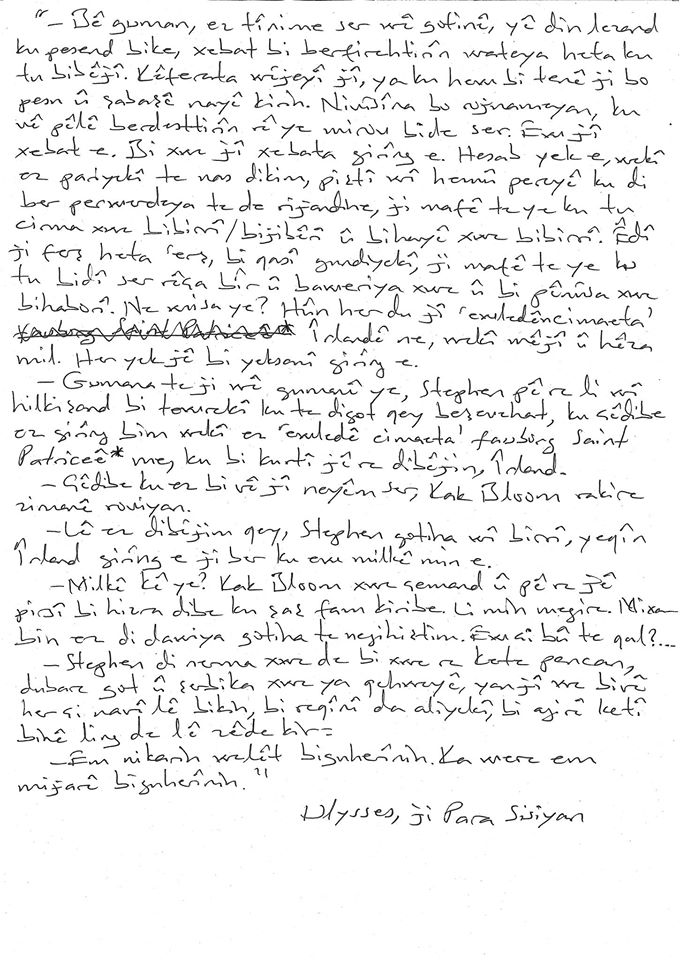

The hardest part of translating James Joyce′s Ulysses into Kurdish was dealing with all the bad language and dirty jokes. How to render ″scrotum-tightening sea″ in a language born in a landlocked range of mountains and plains? How to correctly capture the tone of an offhand reference to masturbating with a candle?

Kawa Nemir, the prolific author and translator of English-language classics into Kurmanji has spent more than five years answering these questions. Last year, Nemir completed the first full translation of Joyce's Ulysses in Kurdish and is set to publish the text through the Istanbul-based Everest publishing house later this year.

"It was frankly very difficult, but also a lot of fun. I have a great love of Joyce and I think that was absolutely necessary in order to finish the job," Nemir said in a recent interview in Istanbul during a lecture tour.

Kurdish literary tradition meets avant-garde modernism

The translation was a trial not only for Nemir, but for the Kurdish language itself, which has a centuries-long literary tradition of epic poetry but is not known for its avant-garde modernism. Nemir began his translation on 16 June 2012 and finished late last year.

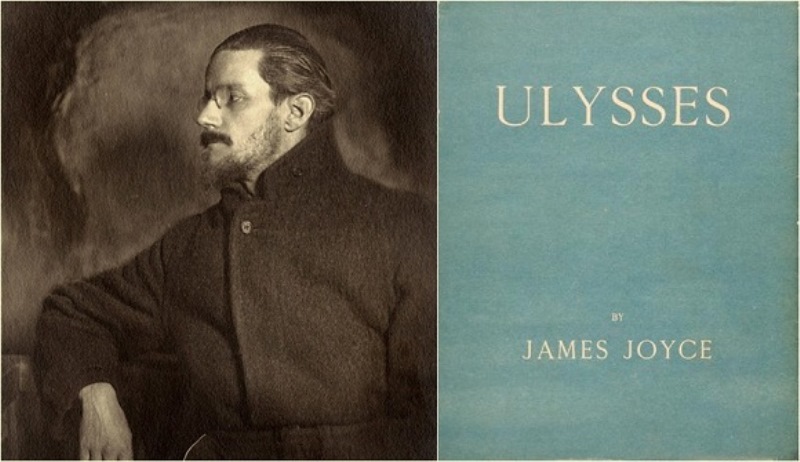

That a full translation has taken so long is less a product of Ulysses’ obscenity than its complexity. The novel is so notoriously unconventional that during the Second World War elements of the British state came to believe it must be a pre-arranged pro-German tract written in code.

″It′s my grand' oeuvre,″ he said. ″Even translating Shakespeare′s plays and sonnets was really only a preparation for translating Ulysses.″

Born in Igdir, a majority Kurdish province in eastern Turkey, Nemir now lives in Mardin in the south-east. As well as having written six volumes of his own poetry, he has published 25 translations of English works in Kurdish, including works of Shakespeare, T.S. Eliot, Emily Dickenson, William Butler Yeats, Sylvia Plath, and Walt Whitman.

A book tour that began in Van last December took Nemir to the cities of Batman, Diyarbakir and Ankara, and culminated in the author speaking at Istanbul′s Bogazici University.

Keeping it apolitical

The current political climate in Turkey is fraught, particularly for Kurds and expressions of Kurdish culture. Over the past three years the country is generally considered to have undergone a marked rise in authoritarianism accompanied by a bloody military campaign in the predominantly Kurdish south-eastern provinces and a large-scale government crackdown on political dissent.

Nemir′s lecture tour was not immune to the difficulties of this climate. At his reading in Van, plain clothes police officers showed up and the event′s organisers were given to understand that the word ″Kurdistan″ should not be uttered.

″You can tell audiences don′t feel free to ask certain questions: they feel under observation,″ Nemir said.

In Syria, Iran, and Iraq, the conditions for Kurdish culture are also beset by war and repression. ″Our generation feels afraid and many have either already left or are planning to leave the region. Those who stay aren′t creating much because we′re all at risk.″

In south-eastern Turkey the conditions are especially harsh. According to Nemir, the small Kurdish literary society that was emerging there just a few years ago now feels directly threatened by the government crackdown.

″They′ve taken a lot of our friends as political prisoners, our websites and forums are monitored and we′re not free to write anything on Twitter for example,″ he said. ″The last two years have been the hardest time of our lives.″

Nemir studied – and has translated from – both English and American literature, but he sees parallels in the Irish literary tradition that are valuable to Kurds today.

″The colonial experiences of Kurds and the Irish bears some similarities,″ he said because of the shared history of British invasion and occupation. ″Of course Irish literature has Swift, Wilde, Joyce, and all those great names. In terms of the status of world literature Kurdish isn′t similar, but I think there is a kind of bridge between the two languages and nations despite their great geographical distance from one another.″

Welcome to the stream of consciousness

The pageant of different textures and registers in Ulysses demanded that Nemir push the borders of his knowledge of his own language. The book′s classical references meant seeking analogies in the classical literary Kurdish of the 17th century poet Ahmed Khani. And Joyce′s extensive use of slang and idiom necessitated an exploration of popular Kurdish slang, an area Nemir believes is under-explored.

″'Ulysses' gives us the opportunity to use everything we have, to play with our own language and national dictionary and to explore traditions that are new to Kurdish literature such as stream of consciousness,″ Nemir said.

Ulysses is challenging enough in its original form and Nemir wants Kurdish readers to get the most from his translation, so he is also preparing a reader′s guide in Kurdish that will explain some of the references, the Kurdish slang choices and introduce the novel to new readers.

Kurdish literature, while acknowledging its own history, needs to come into closer contact with the triumphs of world literature, Nemir says.

Having translated Ulysses, Nemir is now looking to promote a newly published collection of his own haikus written in Kurmanji. With the aim of building another long bridge for his fellow Kurds to another new tradition, Nemir is about to embark on another odyssey across snotgrean seas.

Tom Stevenson and Murat Bayram

© Qantara.de 2018