Out of the cellars and onto the stage

The lights go up, illuminating a minimalistic set. In the middle of the stage is a large, crooked, wooden bookcase filled with books of various sizes and colours. This is the theme of this evening's performance: literature; true literature and the kind that would like to be seen as such.

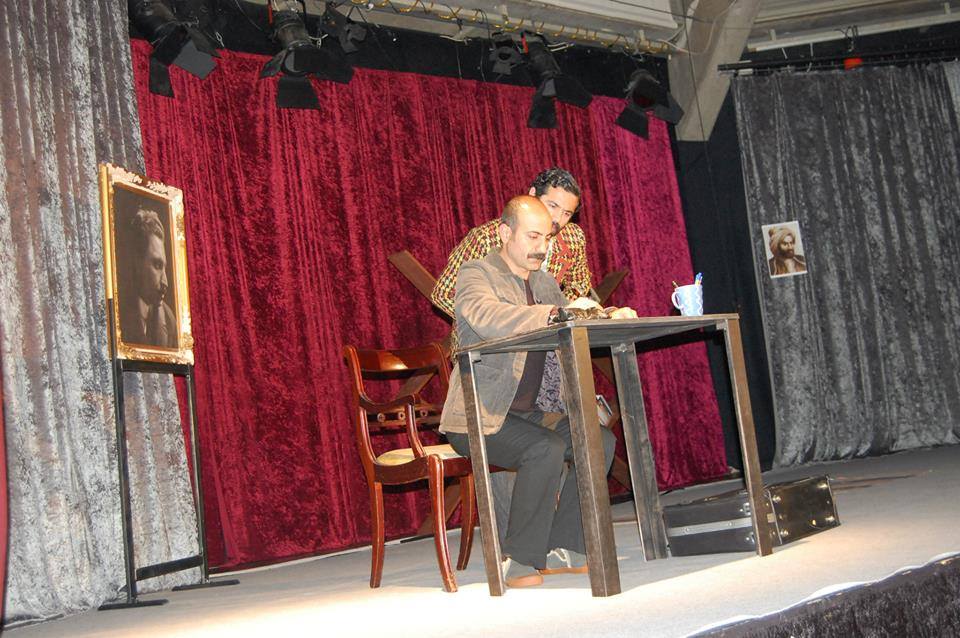

Off to the side of the stage is a small desk. On the wall hang two portraits: that of Ehmede Xani, a Kurdish writer and scholar from the seventeenth century, and Celadet Ali Bedirxan, a writer and politician from the twentieth century. The two are regarded as the founders and champions of the Kurdish national movement.

Lucrative and prestigious

Under the gaze of these popular Kurdish heroes, two men enter the stage. They are Darin, who has been living in Sweden for the past 16 years, and his brother Sadun, who has come for a visit. The reason for his arrival quickly becomes apparent: Sadun hopes to convince his brother to become a writer. Back home, everyone has heard that writing books is an extremely lucrative profession and, above all, a prestigious one. The author's fame would rub off on his kinfolk; the content of the books would be of secondary importance.

Darin shows little enthusiasm for the idea. After a transitional piece in which literary critics are caricatured, the brother leaves, resigned to the fact that he has failed in his mission. From off stage, the author of the play speaks up and pledges to commit this tragic story to paper. Darin insists that it be penned only in his native Kurdish language and should not be translated.

The play, "Esa Zimaneki" (The Pains of Language), which the Istanbul group Teatra Si performed this evening in the Turkish Tiyatrom Theatre in Berlin, was originally a short story written by the well-known, Switzerland-based Kurdish author Hesene Mete. Baran Demir, director and actor, adapted the story into a two-man play.

"The piece takes a critical look at the very nature of Kurdish literature," explains Demir. This is certainly not a new subject, he says, referring to "Hawar" (Help), a journal for Kurdish literature founded by Bedirxan in Damascus in the 1930s. In this journal, Kurdish nationalists and literati discussed this very issue in their articles.

Boom in low-quality literature

"After the 1990s in particular, many Kurds who were not successful at political level turned to writing. As a result, hundreds of books without the slightest literary value were written. The only goal was to get published," explains the actor. The self-critical message of this light-footed comedy is that such books do more harm than good to Kurdish literature. The other message is that Kurdish culture must be fostered.

"It is already something of a sensation in itself that a Kurdish theatre company is performing here in Berlin on a Turkish stage," says organiser Jillian Hoppe, who is also planning further performances in July and September throughout Germany and in other European cities.

Erhan Yildirim, who is accompanying the group on tour, recalls the days in which Kurdish theatre was still clandestinely performed in cellars. In the 1990s, he moved from Malatya to Istanbul in order to help establish the Kurdish theatre scene in the city. At the time, it was still a punishable offence to speak Kurdish in public. "The ceilings in the cellars where we secretly performed were so low that we would bump our heads when we stood up straight," recalls Yildirim. "Very few people came to see us. We were really acting for ourselves." One evening, he recalls, police in civilian clothing stormed a performance. They examined the identity papers of those in the audience and threw the actors, who were still in costume, in prison for the night for the purposes of interrogation. "They wanted to humiliate us," he says.

Positive change in the cultural climate

Since the arrest of Abdullah Ocalan, leader of the PKK, in 1999 and the so-called "Kurdish Opening" initiative of the AKP government, which, among other things, permits the use of Kurdish names and allows the Kurdish language to be spoken, taught and learned, the Kurdish policies of the Turkish government have become less severe, making life much easier for the company.

Today, Teatra Si, which means "Shadow Theatre", is one of four Kurdish theatre companies in Istanbul. In eastern Anatolian cities such as Diyarbakir, more and more Kurdish theatre companies are being set up. Here, against the historical backdrop of the palace of Cemil Pasa, the company recently performed the piece "Mem u Zin" (Mem and Zin), a national epic, which bears similarities to Shakespeare's "Romeo and Juliet".

Kurdish theatre, however, is far from being a permanent fixture on the Turkish theatre scene and it has failed to attract the theatre-going public. As it is, independent, small theatre companies that do not receive state support or funding from other sources have a tough time in Turkey.

According to Demir, the situation for Kurdish theatre groups is even more difficult. They are not even taken seriously. "When Turks don't come to see our performances, the reason isn't because they don't understand the language," explains Demir, who is opposed to the idea of surtitles. "Surtitles only promote assimilation and ensure that our young people no longer make an effort to learn Kurdish," he says.

He is convinced that plays convey feelings and that the audience doesn't necessarily have to understand every word. He sees the lack of audiences for Kurdish plays as being first and foremost a social problem. "In the eyes of many Turks, Kurds and the Kurdish language are inferior. That being the case, they ask themselves whether the quality of our theatre is any better."

More than "Agit-prop"

In addition, there is still the widely held preconception that Kurdish theatre is exclusively a means of spreading propaganda. Demir acknowledges that during the 1990s, most Kurdish plays that were performed were of the "agit-prop" variety. With his company, he would like to prove that Kurdish culture has so much more to offer.

Erhan Yildirim also knows that the spectrum of Kurdish plays is far wider than just "agit-prop". "Orally transmitted role-playing has long been an established feature of our society and is seen as a leisure activity," he explains. Ever since Musa Anter, the Kurdish author, journalist, and founder of the Mesopotamian Cultural Centre in Istanbul, wrote a play in the Kurdish language for the first time in Turkey in the 1990s, the theatre scene has steadily developed. Kurdish epics have been performed, plays by Anton Chekhov have been translated into Kurdish, and dramatists such as Baran Demir have adapted Kurdish short stories for the stage.

Despite these developments, Erhan Yildirim takes an extremely critical view of the supposed success of the government's Kurdish policy of recent years. "People consider the fact they you can now learn Kurdish in private schools to be a success. Yet many people have died or were driven out of their homeland. Villages were burned down. And the fact that I as a taxpayer have to dig deep and pay money out of my own pocket to learn my mother tongue is nothing less than an insult," he says with indignation. Nevertheless, sluggish as it may be, he sees the development of the Kurdish cultural scene as a good start.

Ceyda Nurtsch

© Qantara.de 2014

Translated from the German by John Bergeron

Editor: Aingeal Flanagan/Qantara.de