Strike and counter-strike

The Iraqi prime minister is not to be envied right now. Almost every day, Haider al-Abadi has to mediate, appease or compromise somewhere. He is fighting on all fronts – and not just against the increasingly brutal "Islamic State" (IS) terrorist militia, which all Iraqis call "Daesh".

Abadi also has to manage the mass of domestic political shards that his predecessor Nouri al-Maliki left behind. He not only has to sweep up these shards, but reassemble them as well. The unity of Iraq hangs in the balance. If Abadi doesn't manage to create a mosaic out of the different ethnic groups very soon, the country will fall apart: after all, Maliki succeeded in turning everyone against himself and against each other.

Divide and conquer was Maliki's slogan. And he stopped at nothing in pursuing his aim: the Shia premier fell out with the Kurds over oil; he refused to share power with the Sunnis; he accused the Turkmen of being affiliated with Turkey, with its hostile policy towards Baghdad; and minorities like Christians, Yazidis, Shabak and Mandaeans were forced to the margins and simply ignored.

But it was only when his own Shia coalition partners also started arguing with Maliki that the path was cleared for Abadi, the potential conciliator. In the meantime, "Daesh" had swiftly and brutally overrun the north of the country and set up its own state under Sharia law, which it says is a caliphate. Iraq is threatening to sink into chaos.

A chance for the Iraqi army to redeem itself

Nine months later, the first large-scale military offensive aimed at taking back the areas occupied by "Daesh" and dissolving the caliphate began. The humiliated Iraqi army now has to prove itself. Scores of its soldiers had run away from the advance of the sinister, black-clad barbarians, whose messages of terror broadcast on the Internet were clearly having an effect.

Scenes from the era of the Mongols were repeated between the Euphrates and the Tigris. The mere news of Daesh's horrific deeds drove people to flee. Panicking, soldiers and civilians alike left everything behind in an effort to save their own skin. Even the Kurdish Peshmerga, which translates as something like "look death in the eyes", initially took to their heels when IS attacked Kurdish territory in August 2014.

Nevertheless, they pulled themselves together more quickly than the Iraqi army and began taking back the Yazidi region around Sinjar in December. All the same, parts of the city itself are still in the hands of "Daesh". But in the Kurdish city of Erbil, people are still confident that it is just a matter of time until the terrorists, with their brutal, random violence, are crushed. The Kurdish victory in the battle for Kobani was a psychological turning point for attitudes in this respect.

Great efforts are currently being made to boost the morale of the troops in the Iraqi army. At the recent "Defence and Security Exhibition" in Baghdad (as the exhibition of military devices, weapons and munitions was elegantly called), a general in the Iraqi army flew into a sudden rage when the question of good and evil in his country was raised. All Iraqis were good, he shouted, adding that the evil came from outside: from Europe, America, Saudi Arabia, Chechnya.

He refused to accept that all "Daesh" leaders and a large proportion of their fighters are Iraqi. It cannot be that Iraqis are fighting Iraqis, as they did in 2006/7 and 2008. At that time, Sunnis and Shias killed each other; neighbours murdered neighbours. The shame of this is still deeply ingrained in the Iraqi consciousness. Everyone is adamant that that must never be allowed to happen again. And so, what must never happen again cannot now be happening. As cynical as it may sound, it seems advantageous for the unity of Iraq's various ethnic groups that increasing numbers of foreigners are fighting in the ranks of "Daesh".

The aim is that for the Iraqi army, Tikrit will come to mean what Kobani means to the Kurds: a turning point and a motivational push at the same time. Hopefully, however, it will not take as long to win back the city on the Tigris as it did to regain Kobani on the Syrian-Turkish border. The battle for Kobani went one way and then the other for months, with alternating strikes and counter-strikes.

The military battleground of Tikrit

In spite of all the differences in the course of the fighting to date, the initial situations are still comparable. In both cities, most of the civilian population fled. Tikrit is almost completely empty, so a large number of civilian casualties is not to be expected. It is a military battleground.

But here too, foreigners are causing problems, and not just in the ranks of "Daesh" either, but in the ranks of the government troops as well. Various Shia militias have formed to strengthen the Iraqi army since Grand Ayatollah Sistani in Najaf, which is a sacred place for Shias, said that their mission is to defend the "fatherland and the holy sites".

Saddam Hussein's hometown of Tikrit may not number among those sites, but the city of Samarra to the south does. However, there is an increasing number of reports indicating that Iran is getting heavily involved in the fighting. Iraq's neighbouring country is not only supporting Iraqi Shia militias such as the Badr brigades, "Asaib al-Haq" or Iraqi Hezbollah with Iranian anti-tank weapons, it is also sending its own military equipment and commanders.

Qassem Soleimani, the infamous supreme commander of the Iranian Republican Guard, is said to have set up his command post in Samarra. Iranian tanks are thought to be operating in Tikrit and currently circling the city.

So of all people, it is Saddam's arch-enemy who now wants to take his city? The eight-year-long war between the two countries in the 1980s cost a million lives, until it finally ended in a military deadlock. Each country declared itself the victor.

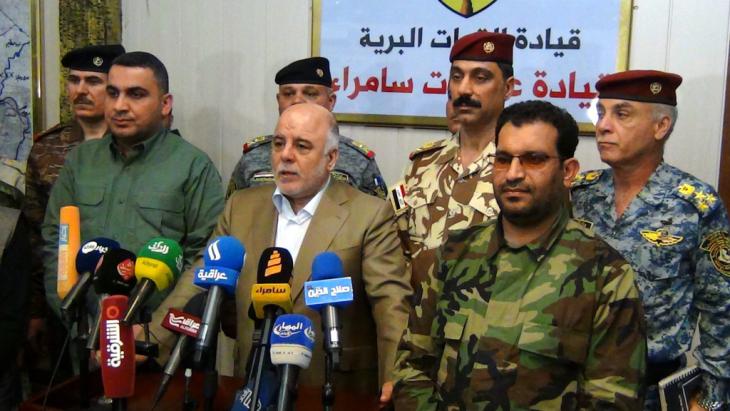

Prime Minister Abadi has recognised the fact that it will not help the process of reconciliation between the two former enemies if the battle for Tikrit is led by Iran. At the moment, he is making media announcements on an almost hourly basis, emphasising that the military operation ordered by him is being led by a purely Iraqi command with the help of the international alliance. For him, this obviously also includes Iran.

Birgit Svensson

© Qantara.de 2015

Translated from the German by Ruth Martin