Punching through the glass

Cartoonist and editor Seth Tobocman writes, in his introduction to the collection, that the work of a cartoonist is to "explain complex political problems in such a way that the simplest person can understand them."

Sabaaneh, who draws for a Palestinian daily, does sometimes condense complex issues into brief, bite-sized messages. In one straightforward image, a prisoner sits behind a glass barrier while his wife and young child sit on the other. In a sort of wish-fulfilment, the prisoner′s hand punches through the glass to touch his unhappy child′s forehead. The message is clear: administrative detention harms families.

Sabaaneh was himself was held in an Israeli prison in 2013 and he writes – in his prefatory remarks – about how that experience changed his compositions. "I had drawn thousands of prisoner-heroes in the past, but in prison I felt completely impotent. Unable to portray myself as a hero, I surrendered to my weaknesses, for we all love, miss, fear and feel pain, and I had to confront the inescapable question: was everything I drew a lie?"

Yet these concerns didn′t stop Sabaaneh from composing fresh works. He "smuggled rough sketches out with every prisoner who was released. When I was released, I collected my sketches and completed the cartoons."

The diaspora and back

Sabaaneh was not raised in Palestine. He grew up in Kuwait and his family moved back to Palestine just before the second intifada began in September 2000. Thirteen years later, Sabaaneh was found himself in an Israeli jail. The charge was "contact with a hostile organisation". This "contact" was ostensibly the publication of several of Sabaaneh′s cartoons in a book written by his brother, who is a member of Hamas.

The five-month imprisonment, which included two weeks in solitary confinement, has been by far the most severe attempt to suppress Sabaaneh′s work. But Sabaaneh has other worries. He was once suspended from his newspaper job for ten days after he drew a cartoon some readers interpreted as irreligious.

Among the cartoons collected in White and Black, the most enjoyable are not the simple newspaper cartoons, but the dense, multi-layered portraits that are crowded with detail. In his introduction, Tobocman writes that there is something Guernicaesque about Sabaaneh′s work. Indeed, many of the most successful pieces depict people in dense spaces, hemmed in by walls, razor wire and distorted weaponry. Many of the figures – both Israelis and Palestinians – have empty, pupil-less eyes and skull-like, rocky faces.

Recurring characters: the separation barrier

The easily identifiable grey slabs of Israel′s "Separation Barrier" are one of the collection′s most powerful recurring images. The state began assembling the wall in 2002, just two years after Sabaaneh′s family moved back to Palestine. Sometimes, the wall separates Israeli neighbourhoods from Palestinian ones, but it also encircles Palestinian towns and separates Palestinians from Palestinians. Often, the cartoon captions are over-reductive and get in the way of the drawings. The cartoon titled "Lives interrupted" shows walls in intensely small sections, separating each person′s life from the next, while "The wall besieges everything" shows people, animals, trees and sky in tiny boxes, hemmed in by sections of wall. The people sit hunched up, their arms around their knees. Even a soldier has a hard time cramming into the small, walled-in space with his gun.

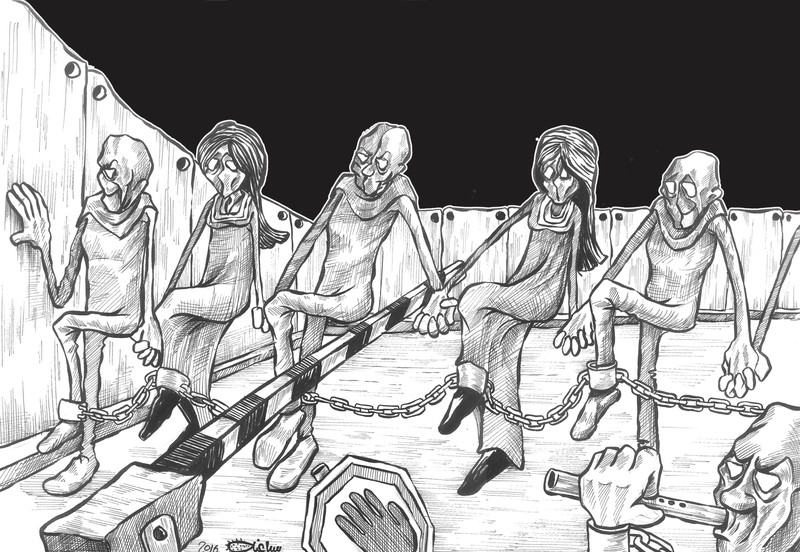

In another drawing, the wall hulks in the background as a line of women and men, with Sabaaneh′s signature skeletal faces, hold hands and dance the dabke. Their legs are chained together and a checkpoint stands between two of them.

In one of the moving multi-panel works, a boy first watches a bird fly over the wall. After that, he flies his kite over. As he′s flying his kite, he imagines it not as an inanimate object, but as a bird tied to a string that he′s keeping behind the wall. The boy cuts the string, allowing the kite to fly free, beyond the wall.

Black ribbons: remembrance and entrapment

Black ribbons, hung on photos of the dead, also appear throughout the collection. In Sabaaneh′s images, ribbons often snake out from the portraits, looping around doves or suffocating the living. In one, an enormous black ribbon emerges from a man′s portrait, ties around a woman′s neck, binds a boy′s hands together, covers another child′s eyes, tangles up a girl′s hair, closes a bird′s beak and even tangles the hands of the clock.

In another, called "Family photos", there are portraits not only of people with black ribbons in the corner, but also of a fish, a paintbrush, a tree, and laundry drying on the line, all apparently deceased. In "Past and present fight for the future", the black ribbon at the edge of a portrait becomes a dripping spigot: those left behind are drowning in the black liquid.

Trapped together: occupied and occupier

Sabaaneh writes, in his introduction, that he acknowledges "in the process of exerting his political will, the occupier is also occupied." He adds that, "In some of my sketches, occupier and occupier are hard to tell apart."

In one of the sketches, given the over-obvious title "All of us are hostages of the place", both the occupier and occupied trapped together in a glass ship-building jug, stoppered by the soldier′s boot. In another, both a man in the watchtower and the people below are counting the minutes, thinking about their loved ones, wishing this charade was over and they could return to a different sort of life.

The cartoons themselves cry out for a different future where both occupied and occupier can break out of their current patterns and frames, past walls and ribbons, into a freer life.

Marcia Lynx Qualey

© Qantara.de 2018

A European edition of this Sabaaneh compilation – "Palestine in Black and White" – is due to be published by Saqi Books on 26 February 2018.