From hardliner to peacemaker

One day in Jerusalem in 1938, Hassan Sidiqui Dajani was murdered in cold blood. A lawyer and chairman of a political party, he had always worked for the coexistence of Arabs and Jews, presumably to the displeasure of the city's grand mufti, Haj Amin El-Husseini. The latter was an admirer of Adolf Hitler who harboured a radical hated of Jews and was an unconditional advocate of Arab autonomy.

History tends to repeat itself, in this case within one family. In April of this year, Hassan's descendent, the Palestinian Professor Mohammed Dajani-Daoudi, was threatened and subjected to harassment on the Internet. His office was vandalised, and numerous protests were organised against him. He was labelled a "collaborator with the Jews" and the "king of normalisation".

After his employer, Al-Quds University in East Jerusalem, and a large number of his colleagues distanced themselves from him publicly, the previously highly regarded 68-year-old professor gave in to pressure and left his chair in American Literature this past June.

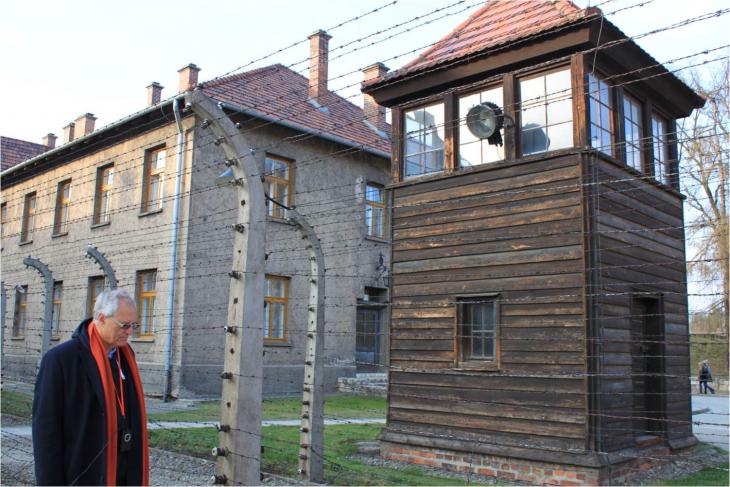

The campaign against Dajani was triggered by a trip to Krakow and Auschwitz in March of this year on which he accompanied 27 young Palestinians.

"Hearts of flesh, not of stone"

The visit was part of a trilateral academic project run by the Friedrich Schiller University in Jena, Germany. Beginning about a year ago, it involved the two Israeli universities in Tel Aviv and Beer Sheva along with Mohammed Dajani.

The focus was on the impact of the suffering and trauma of others on a person's willingness to enter into reconciliation. The project "Hearts of flesh, not of stone", its name inspired by a verse from the Bible, is funded by the German Research Foundation (DFG).

"The first step was to bring about a change in perspectives," explains Dajani. While the Palestinians went to Auschwitz, young Israelis visited the Dheisheh refugee camp near Bethlehem in the West Bank. In future, the project plans to send mixed groups to the sites for a second time, so that they can exchange impressions and experiences.

In any other setting, a visit to a Holocaust memorial would hardly raise eyebrows. In Arab, or more precisely Palestinian, society, however, it's a different matter. How to deal with the Holocaust is still a controversial subject there.

Patchy knowledge and own trauma

This is partly to do with patchy knowledge of the subject and misinformation, says Dajani. "We don't learn anything about it at school." The other factor is the Palestinians' own suffering – the flight and expulsion of what is known as the "Nakba" (catastrophe) – as a direct consequence of the Holocaust. Despite all this, Dajani admits that he had not expected such a harsh reaction to the visit. Nevertheless, he doesn't let it put him off: "It shows how important it is to promote projects like this."

Dajani is doing precisely that with his "Wasatia" forum (Arabic: centre, tolerance, moderation), which was founded in 2007 and which he represents in the trilateral research project. Its goals: a liberal interpretation of the Koran, a two-state solution, the recognition of the state of Israel, dialogue and knowledge about the other side's history. The forum's members organise workshops promoting tolerance and dialogue and hold an annual conference to which Israelis and Palestinians, Muslims and Jews, and politicians are invited.

In times when radicals are gaining the upper hand on both sides in the region, such positions are less than popular. Dajani is aware of this, but says: "people like that are bound only by the present. That's why I invest in the future."

Now calm and collected, the professor was once a radical thinker himself. As a student in Beirut, Dajani was an active Fatah member, responsible for propaganda. "At that time, all that existed was the idea of a united, secular Palestinian state. We were uncompromising and we celebrated ourselves," he says.

Break with Fatah

The Lebanese government expelled him to Syria in 1975 due to his political activities. His subsequent attempt to return using a false passport failed. For eight years, he says, he was unconditionally loyal to Fatah. "Until the day I realised how corrupt the party is and how much nepotism there is there." Then he left Fatah and pursued his academic career in the USA. It was only in 1993, with the aid of a visa for family reunification, that he was able to return to Jerusalem.

It was above all personal experience that made the former hardliner into a convinced peacemaker. "I experienced time and again how difficult problems with the Israelis were solved with the aid of dialogue," he summarises, adding that it is a knowledge of the past that leads to understanding.

The professor puts the visit to Auschwitz in the context of the most recent war in Gaza, which has once again generated hatred and is being fuelled by politicians: "One of the most important lessons for the students in Auschwitz was that the Holocaust didn't happen overnight, but was preceded by a process of anti-Semitic propaganda." This, he points out, laid the groundwork for the genocide.

That's why he considers it so important to strengthen moderate forces. He sees a need to address the section of the Palestinians who are "silently appalled by the suffering of their countrymen in Gaza due to Hamas's policies" and those in Israel who understand the Palestinians' wishes.

Although Dajani refers to himself as an incorrigible optimist, he does not want to found his own party of moderation as an alternative. The Palestinians are not yet ready for that, he says, "I won't experience that in my lifetime." Yet there is hope that a new generation is emerging with more open minds, as evidenced by the student Zeina Barkat. After her visit to Auschwitz, she wrote: "The wall of ignorance has developed a crack." Perhaps one day it will collapse entirely.

Ulrike Schleicher

© Qantara.de 2014

Translated from the German by Katy Derbyshire